Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD 32 – 69

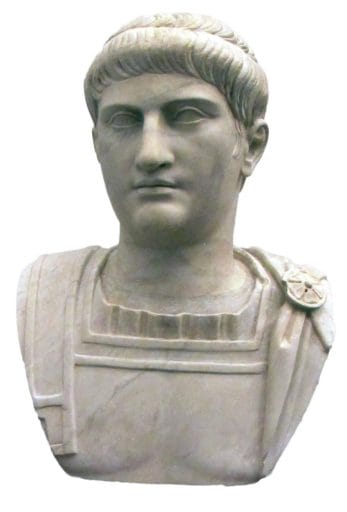

- Name: Marcus Salvius Otho

- Born on 28 April AD 32.

- Governor of Lusitania AD 58-68.

- Became emperor on 15 January AD 69.

- Married Poppaea Sabina, future wife of Nero.

- Committed suicide on 14 April AD 69.

Marcus Salvius Otho was born at Ferentium in southern Etruria on 28 April AD 32. His family did not belong to the old aristocracy, but had achieved political prominence under the emperors. His grandfather had been promoted from equestrian rank to senator by Augustus and even came to hold the consulship, and his father received patrician status from Claudius.

Otho was a companion of Nero, perhaps even his lover, until in AD 58 they fell out over Otho’s wife, the beautiful Poppaea Sabina. Otho ended up being divorced and sent away as governor of Lusitania, leaving the way free for Nero to marry Poppaea himself.

At Galba’s coup against Nero 10 years later, Otho was the first to declare his support.

He subsequently won sympathy with the troops, showing concern for their hardships when on the march to Rome with them.

And once in Rome he became popular with his financial generosity toward the praetorian guard.

Clearly Otho styled himself, at least in his own view, as a potential heir to Galba’s throne. This was based no doubt on the fact hat he had been the first to pledge his support to the emperor.

Though Otho was to be deeply disappointed, when Galba chose Piso Licinianus as his successor.

Instead Otho found other means by which to secure himself the throne. Not merely was Otho popular with the army, but Galba was by then loathed by the troops.

It was therefore not difficult for Otho to involve the praetorians in a plot against Galba.

And so it was that on 15 January AD 69 Otho was invited to the praetorian camp, where he remained, whilst praetorian horsemen set upon and killed Galba and Piso at the Forum. Their severed heads were then brought to him and Otho was hailed emperor by the praetorians.

Faced with such facts, the senate had little choice but to confirm Otho as emperor.

Although, seeing how Otho having taken power, and knowing him a former friend of Nero’s, the senators regarded the new emperor with deep suspicion. Despite this they voted him the usual powers and privileges. And it can be said that Otho, during his short reign, governed with energy and ability.

The provinces in fact swore allegiance to Otho. On temple walls in Egypt he was depicted as pharaoh.

Hoping no doubt to win the favour of the remaining supporters of Nero, Otho ordered that the statues of Nero be restored. He even reinstated some of Nero’s officials.

Though Otho never managed to overcome his reputation for extravagance he had earned in his younger days. And so the quality of his reign came as a surprise to many.

The historian Tacitus reports, ‘Contrary to everyone’s expectation, Otho made no dull surrender to luxury or ease. He put off his pleasures, concealed his extravagances, and ordered his whole life befitting the imperial position.’

In build Otho was a small man with bow legs and feet that stuck out at each side. Vain, he had his body plucked of hairs by servants. He even wore a wig to conceal his thinning hair. Apparently so well-made was this wig, that no-one suspected.

But in his claim for the throne Otho had made a vital miscalculation. Was he popular with the praetorians and with some of the troops he had accompanied on his way back to Rome, he had very little links to the army at all. In his role as governor of Lusitania he had net even had control of a legion.

And yet he depended more completely on the soldiers’ support than any of his predecessors.

His lack of contacts in the army therefore also meant he had little chance to gauge the mood among the troops. Otho was hence completely taken by surprise to learn that in Germany Vitellius had risen to contest his throne. Gaul and Spain immediately declared for Vitellius.

Otho tried to avoid civil war by offering to share power with Vitellius as join emperor. He even proposed a marriage to Vitellius’ daughter. Though Vitellius would have none of it and by March his legions were on the move.

Otho employed a simple strategy. He moved north to delay Vitellius’ advance into Italy. The Danubian legions had declared for Otho and hence the weight of superior forces was on the emperor’s side. Though on the Danube those legions were useless to him, they had to march into Italy first.

To successfully delay Vitellius’ troops in effect meant to win the war. And the powerful Danubian troops were on their way to come to Otho’s aid.

Vitellius’ generals Valens and Caecina knew well that time was on Otho’s side. Hence they forced a fight by beginning the construction of a bridge which would lead them over the Po river into Italy. Otho was left with only two options. Either he would withdraw deeper and deeper into Italy, away from Vitellius’ troops, but so too away from the Danubian forces, or he would stand and fight. Otho decided to fight. His army was totally defeated at Cremona 14 April AD 69.

When the news of defeat reached Otho at Brixellum the following day, the emperor knew himself defeated. Advising his friends and family to take what measures they could for their own safety, he retired to his room to sleep, then stabbed himself to death at dawn the next day, 16 April AD 69.

It may well even be that Otho’s suicide was committed in order to spare his country from civil war. Controversially as he had come to power, many Romans learned to respect Otho in his death. In fact, many could hardly believe that a renowned former party companion of Nero’s had chosen such a gracious end. So impressed were the soldiers by Otho’s final act of courage that some even threw themselves on the funeral pyre die with their emperor.

Otho’s ashes were placed within a modest monument. He had reigned only three months, but in this short time had shown more wisdom and grace than anyone had expected.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.