Last Updated on December 14, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

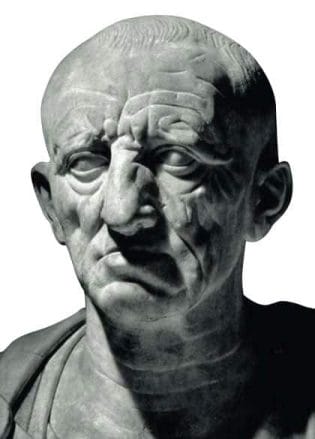

Life: 234-149 BC

Also known as “Cato the Censor“

The progress from quaestor to consul via offices of aedile and praetor was a natural one and came more quickly to men who had proved themselves able soldiers in times of war. However, no one man could hold the same office twice in ten years. Therefore, unless there was a provincial governor needed somewhere, some men could at the very height of their power suddenly find themselves unemployed.

This befell Marcus Porcius Cato, a political leader of great integrity and determination, also known as Cato the Elder to distinguish him from his great-grandson.

Cato the Elder (the additive ‘the Elder’ is used to distinguish him from his grandson who also rose to prominence in Roman history and is known as ‘the Younger’) was born at Tusculum in 234 BC.

He grew up on his fathers country estate and entered military service at the tender age of 17. By 195 BC he had climbed the traditional ladder of magistrative offices to the its very pinnacle by achieving the post of consul. In this position he won a great victory in the wars in Spain.

Then in 191 BC he retired from the army and concentrated instead on participating in debates in the senate.

Cato’s greatest enemy was no lesser than Scipio Africanus, the very commander who defeated Hannibal at Zama. Cato did his utmost to bring the great man down. Scipio enjoyed great popularity and his defeat of Antiochus in Asia only added to his reputation as an outstanding military leader.

But Cato, who undoubtedly was somewhat of a bigot, accused him of leading a decadent lifestyle and pursuing ‘Greek customs’. He even managed to force a court trial which Cato won, but at such a cost to his reputation that he chose to withdraw from politics.

In 184 BC Cato finally found the roel of his life, when he was elected as censor.

He took his role as the guardian of morality incredibly seriously. So much so he used his powers of office to expell Manilius, a candidate in the election for the office of consul, from the senate. This he did, with the reasoning that Manilius had dared to embrace his wife in public, and in full view of his daughter !

Cato ceaselessly sought out those who misused public property. Pipes with which people used to illegally draw water from the public water supply, were simply severed. Private buildings which overlapped onto public land were demolished. The rich suffered enormous taxation, and severe regulations were introduced to prevent any luxuries Cato deemed excessive.

Cato was hated for his pedantic bigotry, but respected as an able politician and good orator.

If you despised him or loved him, Cato’s name shoudl for future generations of Romans become one with both bigotry and sound, honest morality.

He should take his place in history in 150 BC.

Cato’s hate for Carthage was legendary already during his own lifetime.

In spite of the sanctions and conditions imposed on Carthage there was a possibility that it might rise again and once more wreak havoc on the Roman Empire. And Cato the Elder believed this more than anyone else. He sought Carthage’s destruction like no-one else. There is even a tale that he once on purposely dropped a Lybian fig onto the floor of the senate. As a senator picked it up and with others began to admire its size, he used the situation to warn that the land from which this fruit came was only three days away by sea. Furthermore he famously incorporated the words ‘Carthage must be destroyed !’ (Delenda Carthago !) into every speech he held in the senate, no matter what the subject of the matter debated was.

But in 150 BC he was the leader of a Roman commission of inquiry which was to ajudicate between Carthage and Numidia. Carthage, a shadow of its once powerful self after two wars with Rome, was being unfairly harassed by its Numidian neighbours. But Cato, determined in his longstanding hatred for Carthage made sure that the commission found in favour of Numidia, which inevitably led to the Third Punic War and the destruction of Carthage and its civilization.

Though even once retired from politics Cato still wouldn’t rest. He created the first Roman encyclopedia, produced a work on medicine, wrote a history of Rome, and also, due to having grown up on a farm, wrote a text on farming (the oldest complete Latin prose work).

Men in love were thought laughable by Romans, especially old dodderers who married young girls. Yet this is precisely what Cato eventually did. Being a sensible old man, on losing his wife he had married off his son. Cato himself then frequented a certain slave girl, who came to see him every evening in his room, but his son felt that this carrying-on was rather shocking in a house where there was a young bride, his wife. Cato went straight to the forum where his friends gathered around him, forming an escort. Among them was a scribe, Salonius, who had worked at Cato’s house when the the great man had been a magistrate and who had since remained his client. Cato called him over and asked wether he had found a husband yet for his daughter. Salonius replied that he had not, and that he was reluctant to do so without asking Cato’s opinion. ‘Well then’, said Cato, ‘I have found a suitable son-in-law for you, unless you find his age an obstacle. He is a worthy man in all respects, but he is very old.’ Salonius could hardly object. Cato then declared that he himself was the fiancé. Astounded but honoured, Salonius rushed to put his signature on the contract. Cato’s young wife gave him a son who assumed as surname the name of his maternal grandfather, Salonius.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.