Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

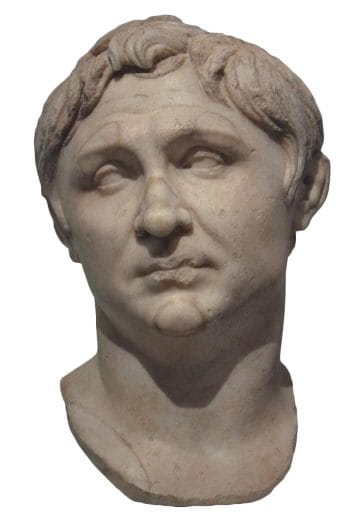

Life: 106 – 48 BC

Name: Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus

Also called: Pompey the Great

Despite his family’s connections to Cinna (an ally of Sulla’s enemy Marius), Pompey raised an army and sided with Sulla, when the latter returned back from his campaigns in the east.

His determination and mercilessness shown when destroying his and Sulla’s opponents in Siciliy and Africa he was nicknamed ‘teenage butcher’.

though despite having shown loyalty to Sulla, he received no advancement or help of any kind from the dictator’s will.

But Pompey soon overcame this setback. The fact that he commanded his own army, made him a force no one coudl afford to ignore. Having used his and proven his ability by putting down a rebellion, he then managed to secure, by means of intimidation, a command in Spain.

Had the commander Metellus Pius been making steady progress against the rebel general Sertorius and his forces, then Pompey, was left with a relatively easy job but received all the glory for himself.

An his return to Italy luck had him come across some of a band of fugitives of the defeated slave army of Spartacus. Once more Pompey was handed easy glory, as he now made claim to have brought an end to the slave war, despite it having evidently been Crassus who defeated Spartacus’ main force in battle.

Pompey had held no government office at all by then. And yet once more the presence of his army in Italy was enough to persuade the senate to act in his favour. He was allowed to stand for the office of consul, despite his lack of administrative experience and his being under the age limit.

Then in 67 BC he received a highly unusual command. It might well have been a commission by those politicians who finally wanted to see him fail and fall from grace. For the challenge he faced was daunting. His objective was to rid the Mediterranean of pirates. The pirate menace had been steadily increasing with the growth of trade and by that time had become utterly intolerable. Though suited to such a challenge, so too the resources he was granted were extraordinary. 250 shops, 100’000 soldiers, 4000 cavalry. Additional to this other countries with interests in Mediterranean trade provided him with further forces.

Had Pompey so far proved himself a capable commander, who at times well knew how to cover himself in glory won by others, then now, alas, he showed his own brilliance.

He organised the entire Mediterranean as wellas the Black Sea into various sectors. Each such sector was handed to an individual commander with forces at his command. Then he gradually used his main forces to sweep through the sectors, crushing their forces and smashing their strongholds. In no more than three months Pompey managed the impossible. and the man, one known as the ‘teenage butcher’, had evidently begun to mellow a little. Had this campaign delivered 20’000 prisoners into his hands, then he spared most of them, giving them jobs in farming.

All Rome was impressed by this enormous achievement, realising they had a military genius in their midst.

In 66 BC, he was already given his next command. For over 20 years the King of Pontus, Mithridates, had been a cause of trouble in Asia Minor. Pompey’s campaign was a total success. Yet as the kingdom of Pontus as dealt with, he continued on, into Cappadocia, Syria, even into Judaea.

Rome found its power, wealth and territory enormously increased.

Cak in Rome all wondered what would happen on his return. Would he, like Sulla, take power for himself ?

But evidently Pompey was no Sulla. The ‘teenage butcher’, so it appeared, was no more. Rather than to attempt taking power by force, he joined up with two of Rome’s most outstanding men of the deay, Crassus and Caesar. He even married Caesar’s daughter Julia in 59 BC, a marriage which might have been made for political purposes, but which became a famous affair of true love.

Julia was Pompey’s fourth wife, and not the first he had married for political reasons, and yet she was also not the first one he had fallen in love with. This soft, loving side of Pompey, won him much ridicule by his political opponents, as he stayed in the countryside in romantic idyll with his young wife. If there was plenty of suggestions by political friends and supporters that he should go abroad, the great Pompey found no end of excuses to stay in Italy – and with Julia.

If he was in love, then, no doubt, so too was his wife. OVer time Pompey had won quite a reputation as a man of great charm and a great lover. The two were utterly in love, while entire Rome laughed.

But in 54 BC Julia died. The child she had born died soon after. Pompey was distraught.

But Julia had been more than a loving wife. Julia had been the invisible link which tied Pompey and Julius Caesar together. Once she was gone, it was perhaps inevitable that a struggle for supreme rule over Rome should arise between them.

For much like gunfighters in cowboy movies, trying to see who can draw his gun faster, Pompey and Caesar would sooner or later want to find out just who was the greater military genius.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.