Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD c.173 – 238

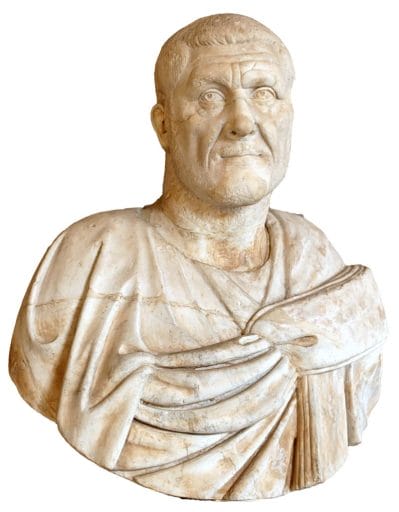

- Name: Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus

- Born AD ca. 173 in the Danube region.

- Became emperor in March AD 235.

- Wife: Caecilia Paulina (one son; Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus).

- Died at Aquileia, April AD 238.

Traditionally the birth of Maximinus is stated as having been either in AD 172 or 173, as was believed by the ancient historians. Today however there is some doubt if this truly was the case. It might indeed well have been that he was born as much as a decade after AD 173, perhaps even later than that.

Despite him being known as Thrax (the Tracian) it is actually believed that he was from Moesia, the son of a Gothic father and an Alan mother.

Maximinus was truly a mountain of a man. Surely the largest man ever to hold imperial office, the Historia Augusta states him at 8 ft 6 in tall (2.6 metres), and so strong that he could pull an ox cart on his own.

Maximinus was a harsh man, too harsh perhaps. But his military achievements mark him out as much more than the brutish illiterate peasant, which many historians describe him as. Extraordinarily brave and physically overwhelming he was the ideal soldier. Though the historians were clearly right in their opinion that Maximinus lacked what it needed to be an emperor.

Maximinus began his remarkable career as a simply soldier in a Thracian auxiliary unit. His legendary physical prowess had him rise up the military ladder.

By AD 232 he might have commanded a legion based in Egypt and played a leading role in the campaign against the Parthians by Alexander Severus. In fact he briefly became governor of the reconquered province of Mesopotamia.

Then, in AD 235, he was on the Rhine in command of a force of recruits from Pannonia, when the payments to the Alemanni enraged the army against their emperor Alexander Severus. Was Alexander generally seen as a weak commander with doubtful achievements in Mesopotamia, then now the army’s men saw a stern, awesome military leader in Maximinus. The army revolted, killed Alexander Severus and his mother Julia Mamaea, and proclaimed the giant Maximinus emperor.

The senate found itself in no position to object and simply confirmed Maximinus as emperor. But there was much ill-feeling about this elevation. Not only had the senators not been consulted at all, but Maximinus was a coarse peasant, whilst the emperor they had just lost had been mild and benevolent ruler.

Maximinus knew that the war against the Alemanni was of paramount importance. For it was the very reason because of which his predecessor had been killed.

But first the new emperor need to deal with potential internal rebellions. At first, while he was trying to begin a campaign across the Rhine, a group of officers, backed by influential senators, planned to cut the bridge of boats leading across the river, helplessly stranded the other side. At his subsequent death at the hands of the Germans they intended to proclaim the senator Magnus emperor.

But the conspiracy was betrayed and Maximinus had all the suspects executed.

Then there followed a very brief crisis among the eastern archers (Mesopotamians from Osrhoene) which had come to the Rhine with Alexander Severus and still held dear his memory. They invested as emperor one of the Alexander’s friends, Quartinus. But their leader Macedo then changed sides and instead killed Quartinus.

The threats had been averted, but did take a toll on the emperor who thereafter remained deeply suspicious of everyone.

With senators being to most obvious threat to him as they were the likeliest candidates for imperial office, he had them all removed from the army, replacing them with loyal soldiers who owed their previous promotions to him.

These revolts having been dealt with, Maximinus then crossed back over the Rhine and drove deep into Germany, his troops marauding the country. A decisive battle then was fought in a swamp near the border dividing today’s regions of Württenberg and Baden. The emperor is said to have himself been chest-high in the water at times, urging on his men, leading them, despite heavy losses, to a devastating defeat over their enemy. The Alemanni, badly mauled by the Roman forces, would thereafter remain at peace for some time.

Celebrating his victory Maximinus promoted his son Maximus to the rank of Caesar (junior emperor).

Maximinus then went about strengthening the German border defences, but was soon called to deal with troublesome Dacian and Sarmatian tribes along the Danube. He spent the winter of AD 235-36 at Sirmium and then led successful campaigns against these tribesmen.

As a military leader Maximinus was an outstanding man, but as a ruler of empire his methods were coarse and short-sighted. To fund his campaigns he confiscated and extorted funds from the property owning classes. He even raided the funds for the poor (alimenta) and tampered with the corn dole in desperate measures to pay for his military expeditions.

This in turn made sure that Maximinus, though highly successful in battle, became deeply unpopular among all his subjects.

It was in the spring of AD 238, Maximinus was still at Sirmium, that news reached him of a revolt.

The governor of Africa, Marcus Antonius Gordianus Sempronianus, together with his son had been hailed emperors at Carthage. Maximinus quickly set about preparing his troops and marched on Italy. But as he was on the way the revolt of the Gordians, lasting only 22 days, was already put down by the governor of Numidia, Capellianus.

But the crisis was far from over. The senate, which had clearly supported the Gordians and which was determined to rid itself from the common soldier on the throne now pronounced no fewer than two new emperors, Pupienus and Balbinus, with the young Gordian III as Caesar.

And so Maximus continued on, seeking to win his throne back. Commanding the powerful Danubian legions, the odds seemed in his favour. But as Maximinus reached Emona in northern Italy he found it deserted. The entire town had been evacuated by his opponents. There was no food. All had been destroyed.

The troops’ morale sunk drastically. Nonetheless he continued on to the city of Aquileia. But there he found the city gates closed. Despite his offers of rewards and amnesties, Maximinus was refused entry. Enraged he sought to take the city by storm, but his attack was repulsed and his troops suffered heavy losses.

Maximinus now found himself in desperate straits. With no food for his troops, he could go no further.And so he resolved to besiege Aquileia. He might have succeeded, were it not for the severe discipline he demanded of his men. With morale low and a severe lack of food, he pushed matters too far by treating his officers and troops to harshly at this time of crisis.

On 10 May AD 238 some of the troops, most of all those whose families were in territory held by the enemy(the Praetorians and the Legio II ‘Parthica’), rose in revolt and killed Maximinus and his son Maximus.

Their heads were severed and carried to Rome by a group of cavalrymen.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.