Last Updated on November 27, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD 270 – 313

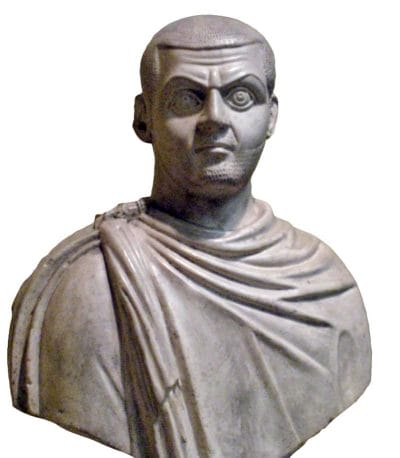

- Name: Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximinus

- Born 20 November AD 270 in the Danubian region.

- Became emperor in 1 August AD 310.

- Wife: unknown (one daughter; unknown).

- Died at Tarsus July/August AD 313.

Maximinus Daza (Also called “Maximinus II Daia”) was born on 20 November AD 270 in the Danubian region as the son of a sister of Galerius. He started his life as a herdsman of cattle, but then joined the army.

With his uncle Galerius’ rise to power, he advanced through the army at a very fast rate.

By the time of the joint abdication of Diocletian and Maximian in AD 305 he was serving as a military tribune and had been adopted as Galerius’ son. It was from this position of tribune, that he was directly promoted to to the rank of Caesar, with responsibility for the diocese of Oriens, which included the important provinces of Syria and Egypt.

It is at the point of his accession to Caesar that he assumed the more regal names Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximinus. Meanwhile to yet further strengthen the bond between himself and Galerius, his daughter was betrothed to Candidianus, the son of Galerius.

Maximinus II quickly proved to be a fervent believer in the old Roman gods determined to repress the Christian faith. And so he continued the harsh policies introduced against the Christians under Diocletian.

In AD 308 at the Conference of Carnuntum Maximinus II, together with the other Caesar Constantine, received a severe blow to their status as heirs to the Augusti, when Galerius raised Licinius to the vacant position of co-Augustus.

The rules of the tetrarchy clearly would have demanded one of the Caesars to be promoted to this post, Constantine in particular who was the western Caesar. But his close ties to Galerius obviously had built up Maximinus II’s hopes. If was Constantine disappointed, then Maximinus II was truly seething at this decision. His hostility towards Licinius was to remain a constant reminder of this denial of the status of Augustus in AD 308.

But for the moment all who got to feel this anger were the Jews and the Christians. In AD 309 Maximinus II’s pagan fanaticism went so far as to demand that everyone, even babies, were to attend the public sacrifices to the state gods.

For a while Maximinus II continued to sulk angrily at being passed over, but then in AD 310 he took the decisive step and had himself acclaimed Augustus by his own troops.

Galerius could do little else but accept the usurper in the east, perhaps even feeling sympathy for some of the ill feeling on his adoptive son’s side.

Maximinus II Daia is described by ancient historians as a vicious, boorish, uneducated tyrant. Particularly when considering his brutal persecution of the Christians, this well appears to have been the case. But naturally much of his legacy has been passed down by Christian historians who understandably displayed great bias against this emperor.

Was he no doubt a tyrant, then one perhaps must also consider that the surviving relatives of the emperors Severus II and Galerius chose to live in his domain, rather than under the rule of the other emperors. In fact Licinius did eventually see them all put to death.

When in AD 311 Galerius died, both Licinius and Maximinus II knew they had to act fast to secure the territory of the dead Augustus. Both were clearly enemies, ever since Licinius had been granted the throne of Augustus instead of Maximinus II.

Licinius was weak, only having Pannonia in his control, but the Balkan territories were in easy reach. However, Maximinus II found it easy to occupy all of Asia Minor (Turkey), with Licinius being powerless to do anything to prevent it. then with the armies of either emperor facing each other across the Bosporus, the two men agreed that the Bosporus was to be their border.

Had Galerius on his deathbed made his famous edict (possibly prompted by Constantine) by which toleration should be granted to the Christians, then Maximinus II only followed this for six months, after which he reverted back to his policy of persecution.

This persecution was now back up with a potentially greater threat to the Christian church than the persecution itself. For Maximinus II now remodelled the pagan cult system itself, following the example of the Christians church. This in effect created a pagan church, with a similar organization and hierarchy to the Christian one.

However, Maximinus II’s new persecution of the Christians was to be remembered most for its use of forged documents, by which he tried to discredit the Christian faith. Most notorious of all among those papers should be the infamous Acts of Pilate.

Maximinus II had strengthened his position by the occupation of Asia Minor but hoped most of all to find an ally in Maxentius who controlled Italy and was also a traditional pagan.

But in AD 312 Constantine’s victory over Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge put an end to such hopes.

More so Constantine used his newly enhanced authority to order Maximinus II to cease his persecution of the Christians. The latter reluctantly complied. No doubt he realized that with Licinius and Constantine acting in favour of the Christians any refusal on his part might have given them an excuse to jointly act against him.

Had Constantine made advances in the west, Maximinus II only suffered setbacks in the east. Failed harvests, plagues, robber bands on the loose and a revolt by the Armenians decisively weakened his position at this moment.

Maximinus II knew it inevitable that the current position of three hostile emperors could only result in civil war until one had achieved absolute power. Constantine’s victory at the Milvian bridge made him the strongest of the three by far. And the ambitious Constantine was definitely the greatest threat. Though a war with Constantine was not possible. But for the Libyan desert he had no real border with any of Constantine’s territories.

And so any action would have to be directed at his old enemy Licinius, who was Constantine’s ally, even engaged to his sister Constantia.

Yet such things would change. If Constantine would ever get his hands on Licinius’ Danubian provinces, Maximinus II would stand no chance against a foe of such strength. Yet, if he could conquer Licinius’ territory himself, his strength would equal that of Constantine.

With this in mind, Maximinus II marched his troops across Asia Minor (Turkey) in the winter of AD 312/313. It was freezing, spring had not yet come.

Maximinus II’s idea was most likely two fold. Firstly, such an attack outside the warmer seasons traditionally used for warfare would take Licinius by surprise. And secondly Constantine was occupied with the Germans on the Rhine, offering Maximinus II a golden opportunity to attack Licinius without his ally being able to come to his aid.

If this was the plan, then the harsh, icy conditions imposed on his army were enormously demanding.

Having crossed the Bosporus with 70’000 men, his luck held at first. The city of Byzantium surrendered to his force.

But Licinius, now aware of Maximinus II’s plans, marched against him. On 30 April or 1 May AD 313 the two armies met, Maximinus II controlling a force more than twice the size than that of Licinius. But after the forced marches across the frozen mountains of Asia Minor, his troops were exhausted.

Simply too exhausted to fight, his army was utterly defeated.

Maximinus II escaped the slaughter and made his way back across the Bosporus disguised as a slave.

With the army of Licinius in pursuit he fled Asia Minor, hoping to re-group behind the Taurus mountain range and recover his position.

He established his new headquarters at Tarsus and began to fortify the passes in order to prevent Licinius’ advance. But Licinius could not be held back. He broke through the Taurus mountains and laid siege to his Maximinus II at Tarsus.

Besieged by land and sea, Maximinus II’s situation was hopeless.

At this point he fell ill. Either this was due to disease or due to having taken poison to kill himself. In either case he wasted away rapidly. Blinded and suffering, Maximinus II Daia died a miserable death in Tarsus in August AD 313.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.