Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD c. 204 – 249

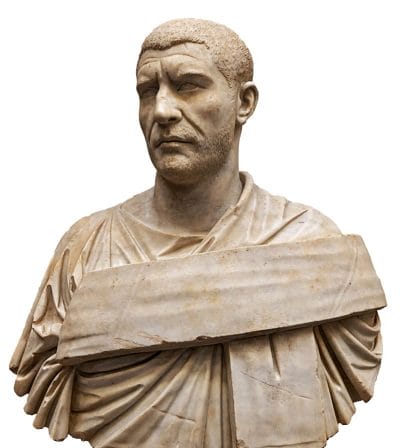

- Name: Marcus Julius Verus Philippus

- Born AD ca. 204.

- Consul AD 245(?), 246(?), 247.

- Became emperor in 25 February AD 244.

- Wife: Marcia Otacilia Severa (one son; Marcus Julius Philippus).

- Died at Verona, Sept/Oct AD 249.

Philippus was born in about AD 204 in a small town in the region of Trachonitis in south-western Syria as the son of an Arab chieftain called Marinus, who held Roman equestrian rank.

He was to become known as ‘Philip the Arab’, the first man of that race to hold the imperial throne.

He was the deputy of the praetorian prefect Timesitheus at the time of the Mesopotamian campaigns under the reign of Gordian III.

At the death of Timesitheus, which some rumours claim was the work of Philippus, he acceded to the position of commander of the praetorians and then incited the soldiers against their young emperor.

His treacherousness paid off, for the troops not only hailed him emperor of the Roman empire but on the same day also killed Gordian III in order to make way for him (25 February AD 244).

Philippus, eager not to be understood as the murder of his predecessor, had a report sent to the senate, claiming that Gordian III had died of natural causes, and even prompted his deification.

The senators, with whom Philippus managed to establish a good relationship, thus confirmed him as emperor.

But the new emperor was well aware that others had fallen before him, due to their failure of making it back to capital, leaving others to plot. So Philippus’ first act as emperor was to to reach agreement with the Persians. Though this hasty treaty with the Persians hardly won him much praise. Peace was bought with no less than half a million denariito Sapor I and thereafter an annual subsidy was paid.

After this agreement Philippus put his brother Gaius Julius Priscus in charge of Mesopotamia (and later made him commander of the entire east), before he made his way to Rome.

Back in Rome, his father-in-law (or brother-in-law) Severianus was granted the governorship of Moesia.

This appointment, together with that of his brother in the east, shows that, having reached the throne himself by betrayal, Philippus understood the need to have trustworthy people in important positions.

To further increase his grip on power he was also sought to establish a dynasty. His five or six year old son Philippus was declared Caesar (junior emperor) and his wife, Otacilia Severa, was declared Austusta. In a more strained attempt to increase his legitimacy Philip even deified his late father Marinus. Also his insignificant home town in Syria was now elevated to the status of a Roman colony and dubbed ‘Philippopolis’ (City of Philip).

Some rumours have it, that Philippus was the first Christian emperor. This though appears untrue and is most likely based on the fact that he was very tolerant toward the Christians.

A simple explanation to dispel Philip’s being a Christian, is to point to the fact that he had his own father deified.

Philip is also known to have clamped down on abuses in the treasury administration. He felt a deep dislike for homosexuality and castration and issued laws against them. He maintained public works and improved some of the water supply to the western part of Rome. But he could do little to ease the burden of extortionate taxes to pay for the large armies the empire required for its protection.

Philippus was not yet long in office when news arrived that the Dacian Carpi had crossed the Danube. Neither Severianus, nor the generals stationed in Moesia were able to make any significant impact on the barbarians.

So towards the end of AD 245 Philippus set out from Rome himself to deal with the problem. He stayed at the Danube for much of the next two years, forcing the Carpi and Germanic tribes such as the Quadi to sue for peace.

His standing on his return to Rome was much increased and Philippus used this in July or August AD 247 to promote his son to the position of Augustus and pontifex maximus. Furthermore in AD 248 the two Philips held both consulships and the elaborate celebration of the ‘thousandth birthday of Rome’ was held.

Should all this have put Philippus and his son on a sure footing, in the very same year three separate military commanders rebelled and assumed the throne in various provinces. First there was the emergence of a certain Silbannacus on the Rhine. His challenge to the established ruler was a brief one and he vanished from history as quickly as he emerged. A similarly brief challenge was that of a certain Sponsianus on the Danube.

But in early summer of the year AD 248 more serious news reached Rome. Some of the legions on the Danube had hailed an officer called Tiberius Claudius Marinus Pacatianus emperor. This apparent quarrelling among the Romans in turn only further incited the Goths who were not being paid their tribute promised by Gordian III. So the barbarians now crossed the Danube wreaking havoc in northern parts of the empire.

Almost simultaneously a revolt erupted in the east. Philippus’ brother Gaius Julius Priscus, in his new position as ‘praetorian prefect and ruler of the east’, was acting as an oppressive tyrant. In turn the eastern troops appointed a certain Iotapianus emperor.

On hearing this grave news, Philippus began to panic, convinced the empire was falling apart. In a unique move, he addressed the senate offering to resign.

The senate sat and listened to his speech in silence. Alas, the city prefect Gaius Messius Quintus Decius rose to speak and convinced the house that all was far from lost. Pacatianus and Iotapianus were, so he suggested, bound to be killed by their own men soon.

If both the senate as well as the emperor took heart from Decius’ convictions for the moment, they must have been highly impressed, when in fact what he predicted came true. Both Pacatianus and Iotapianus were shortly afterwards murdered by their own troops.

But the situation on the Danube still remained critical. Severianus was struggling to regain control. Many of his soldiers were deserting to the Goths. And so to replace Severianus, the steadfast Decius was now sent to govern Moesia and Pannonia. His appointment brought almost immediate success.

The year AD 248 was not yet over and Decius had brought the area under control and restored order among the troops.

In a bizarre turn of events the Danubian troops, so impressed by their leader, proclaimed Decius emperor in AD 249. Decius protested he had no desire to be emperor, but Philippus gathered troops and moved north to destroy him.

Left with no choice but to fight the man who sought him dead, Decius led his troops south to meet him. In September or October of the AD 249 the two sides met at Verona.

Philippus was no great general and by that time suffered from poor health. He led his larger army into a crushing defeat. Both he and his son met their death in battle.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.