Last Updated on November 3, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

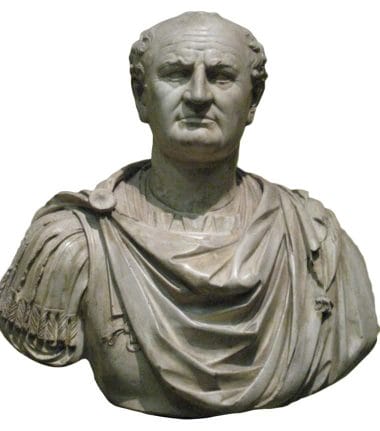

Life: AD 9 – 79

- Name: Titus Flavius Sabinus Vespasianus

- Born 17 November AD 9 at Reate.

- Served in Thrace, Crete, Cyrene, Germany, Britain and Africa. Military commander in Palestine AD 66-69.

- Became emperor in AD 69.

- Married Flavia Domitilla, who died AD 65 (two sons, Titus and Domitian, and one daughter Domitilla).

- Died on 24 June AD 79. Deified in AD 79.

Titus Flavius Sabinus Vespasianus was born in AD 9 at Reate, north of Rome. His father Flavius Sabinus was a tax collector and held equestrian rank. His mother, Vespasia Polla, belonged to an equestrian family, and her brother managed to become a senator.

Vespasian and his brother Sabinus also managed to follow in their uncle’s footsteps and become senators.

Early Career

In AD 39 Vespasian married Flavia Domitilla. It was not necessarily a good match for a man seeking a high-flying career. Flavia was not even a full Roman citizen and had been the mistress of a Roman equestrian in Tripolitania. It appears their marriage was truly one inspired by love, rather than political ambitions. Flavia and Vespasian did have three children together. Though she died long before Vespasian was to become emperor. And he would still remember her with great affection when he came to power.

During the reign of Tiberius Vespasian was a military tribune in Thrace and then went on to serve as praetor in Crete and Cyrene. In AD 40 Vespasian was made praetor under Caligula and under Claudius, he enjoyed patronage of the powerful minister Narcissus.

During the invasion of Britain during AD 43-47 he commanded a legion (the II ‘Augusta’) and distinguished himself with military successes in the south and southwest of England. In particular, he made himself a name with the effective use of ‘artillery’ when assaulting heavily defended positions fortified by earthworks, and had been responsible for taking the Isle of Wight.

Vespasian as a Consul

This success led to Vespasian’s election as consul for AD 51, and in AD 63 he was proconsul of Africa, his administration winning much praise. This praise was won largely due to Vespasian not following the usual course of milking the province for his own financial gain. In turn, however, he did suffer private financial problems and only avoided bankruptcy with help from his brother Sabinus.

Though in AD 66, as a member of Nero’s imperial entourage in Greece, the gritty down-to-earth soldier Vespasian committed the ultimate sin by either walking out or falling asleep during the course of one of Nero’s recitals. He fell from grace and fled to some obscure country town, hiding in fear for his life.

But in AD 67 he was offered a province and an army command of three legions by Nero. If the emperor was mad and wanted to see Vespasian dead, he needed him now. The Jewish rebellion of AD 67 called for a commander who knew of ways to oust the Jews from their walled cities. Someone had obviously reminded the emperor of Vespasian’s record against the defensive earthworks in Britain.

At the age of fifty-eight, Vespasian headed for Judaea, directed the reduction of Jotapata in the north, and began the preparations for the siege of Jerusalem. On hearing of Nero’s death, Vespasian formally recognized the accession of Galba.

Succession in Rome

When news arrived of Galba’s murder in early AD 69, Vespasian was prompted to consider rebellion. He had on his side the governor of Syria, Gaius Licinius Mucianus. At first, the two had not gotten along well, mainly due to Mucianus resenting that Vespasian’s military command had been given higher status by Nero than his governorship, but now they both needed allies to weather the crisis following the death of two emperors.

After Otho’s suicide in April AD 69, they formed plans to take action. They both acknowledged Vitellius’ accession, but meanwhile secretly enlisted the support of Tiberius Julius Alexander in Egypt. Mucianus had no sons of his own to be his heirs. Alexander was only of equestrian rank – and a Jew. Neither therefore could be considered as potential emperors. Vespasian though had two sons, Titus and Domitian, who were of senatorial rank and had held the consulship. All three agreed, that he should be their candidate for the throne.

On the way to the Throne

On 1 July, Alexander commanded the legions in Egypt to swear an oath of allegiance to Vespasian. Within two weeks the armies in Judaea and Syria had followed that example. The plan was that Mucianus would lead twenty thousand men into Italy, with Vespasian remaining in the east, where he could control the all-important Egyptian grain supply to Rome. Though by late August the Danubian armies also declared themselves for Vespasian.

Antonius Primus, commander of the Sixth Legion in Pannonia, and Cornelius Fuscus, imperial procurator in Illyricum, led the Danube legions in a rapid descent on Italy. They commanded a relatively modest force of five legions, perhaps 30.000 men, which was only half of what Vitellius had at his disposal in Italy.

The Second Battle of Cremona began on 24 October AD 69 and ended the next day in a complete victory for Primus and Fuscus. On 17 December AD 69, an army was sent to fight Primus and Fuscus defected to them at Narnia, leaving the way free to Rome. When Vitellius learned of this he tried to abdicate and Vespasian’s elder brother Titus Flavius Sabinus, city prefect of Rome at the time, attempted to take control of the city. But he and his supporters were attacked by Vitellius’ soldiers and killed.

Two days later, on 20 December, the army of Primus and Fuscus fought its way into Rome against a determined defense. The following day the senate confirmed Vespasian as emperor. Mucianus arrived soon after. Until Vespasian’s arrival, Mucianus ruled on his behalf alongside the emperor’s younger son Domitian who had been in Rome throughout the troubles.

Vespasian now headed for Rome, leaving his son Titus behind to capture Jerusalem, and arrived at Rome in October AD 70. He was almost 61 but he was still fit and active. Soon after Titus in Palestine brought an end to the Jewish revolt (although the siege of Masada continued until AD 73) and in the north Cerealis defeated the Gallo-German uprising at Augusta Trevivorum. In effect, Vespasian, an old military veteran, was the man who could finally deliver peace to the empire.

Vespasian as the Emperor

Vespasian possessed insight and a sense of how to maintain peace, too. Though the destruction of Jerusalem and the retaliation against the Jews were carried out with unnecessary severity, and restrictions were placed on some of their practices, Jews were excused from Caesar’s worship.

His relationship with the Senate was a mixed one. He attended the meetings of the senate and consulted the senators with great care. But the day he chose to date his accession was not 21 December AD 69, when the senators had recognized him, but 1 July AD 69 when he had first been acclaimed emperor by his troops. In short, he respected the senate for its ancient tradition and dignity, but he made it evidently clear that he knew the true power to lie with the army.

On his son Titus’ return to Rome from Palestine in AD 71, Vespasian formally made him his associate in government, granting him the title of Caesar, and appointed him commander of the imperial guard, a sound move considering the role the praetorians had played in establishing and overthrowing previous rulers.

Also in AD 71, he instituted the first salaried public professorship when he appointed Quintilian (AD 40-118) to a chair of literature and rhetoric. He also exempted all doctors and teachers of grammar and rhetoric from paying taxes Under Vespasian, too, a new class of professional civil servants was created, drawn largely from the business community. In AD 73-74 Vespasian, like Claudius had done before him, revived and occupied the office of censor together with his son Titus in order to have control over membership to the senate.

With the empire devastated by civil war, Vespasian needed to steeply increase taxation to cover the empire’s vast costs. These measures soon earned him an undeserved reputation for meanness and greed. Vespasian was keen to lead by example and led a life free of extravagance and luxury in order not to further burden the provinces with the cost of his imperial office. Vespasian in any case appears not to have had a taste for extravagant living. He was a brilliant and tireless administrator, with a gift, so often lacking in his predecessors, of picking the right man for a job.

His usual daily routine while the emperor was as follows. He would rise early, even when it was still dark. He would perhaps read letters and official reports, before letting in his friends, putting on his shoes, and getting dressed. After dealing with any other business he would then perhaps go for a drive in a chariot. Later he would share a bed with a concubine, of whom he had several to take the place of his dead mistress, Caenis. After that, he was usually in his best mood, so his staff was eager to approach him with any requests or problems at that time.

Vespasian was indeed noted for mildness and a healthy sense of justice. For example, he helped Vitellius’ daughter to find a suitable husband and even provided her with the dowry. At first, Vespasian relied on Mucianus as his principal aide and advisor. Though from when Mucianus died ca. AD 76 he began more and more to rely on his elder son Titus. It was clearly understood by all that Titus would succeed his father to the throne.

Emperor Vespasian Cured by Veronica’s Veil, tapestry, circa 1510

Later Years and Death

Such dynastic plans led to some hostility, particularly among senators who still objected to the hereditary principle being applied to the creation of emperors. In particular, since the hereditary lineage of the Julio-Claudians had led to disaster. The most dangerous of such objections came to light in AD 79 when a plot against Vespasian’s life two eminent senators, Eprius Marcellus and Caecina Alienus, was uncovered. Titus was fast to act and neither of the two conspirators survived.

Not long afterward Vespasian fell ill, withdrew to his summer retreat at Aquae Cutiliae in the Sabine mountains, and died on 24 June AD 79. Vespasian died of natural causes and, according to the historian Suetonius, with great dignity. Even on his deathbed his humor still showed in a final jest, ‘Vae, puto deus fio’ (‘Woe, I think I’m turning into a god.’)

People Also Ask:

What was Vespasian famous for?

He established the new, Flavian dynasty. Born to a Roman knight and tax collector, Vespasian was a man of relatively humble origins and played on these roots to great political advantage.

Was Vespasian a good leader?

He was upright and courageous both in his military and political leadership, instilling discipline and loyalty in his troops and making sometimes unpopular decisions to help restore stability to the Roman state.

What are two major things Vespasian is known for?

His fiscal reforms and consolidation of the empire made his reign a period of political stability and funded a vast Roman building program which included the Temple of Peace, the Colosseum, and restoration of the capitol.

Who built the Colosseum?

Construction of the Colosseum began under the Roman emperor Vespasian between 70 and 72 CE. The completed structure was dedicated in 80 CE by Titus, Vespasian’s son and successor. The Colosseum’s fourth story was added by the emperor Domitian in 82 CE.

What was Vespasian’s downfall?

Vespasian did not experience downfall as the word would typically mean since he succumbed to natural causes reasonably old age.

What do people think of Vespasian?

The Roman people loved him and his sons, and they also enjoyed the peace that his reign afforded them. He was stable-minded and wise in old age, something the people had lacked in their previous rulers like Nero and Caligula.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.