Last Updated on October 22, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

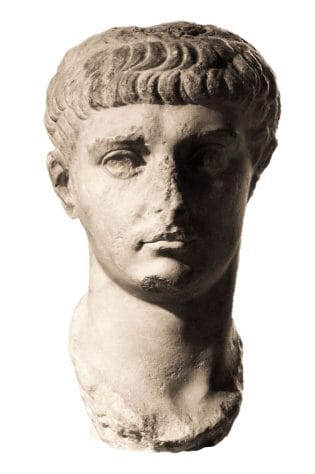

Life: 10 BC-AD 54

- Name: Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus

- Born on 1 August 10 BC at Lugdunum, Gaul

- Son of Nero Claudius Drusus (38-9 BC), brother of Tiberius, and Antonia (36 BC-AD 37), daughter of Mark Antony.

- Became emperor in AD 41.

- Married (1) Plautia Urgunlanilla (one son, Drusus, (d ca. AD 26) and one daughter, Claudia); (2) Aelia Paetina (one daughter, Antonia); (3) Valeria Messalina (one son, Tiberius Claudius Britannicus (AD 41 -55) and one daughter, Octavia (d. AD 62); (4) Agrippina.

- Died on 12 October AD 54.

- Deified in AD 54.

Early Life of Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus was born in Lugdunum (Lyon) in 10 BC as the youngest son of Nero Drusus (Tiberius’ brother) and of Antonia the younger (who was the daughter of Marc Antony and Octavia).

Suffering from ill health and an alarming lack of social skills, for which most believed him mentally handicapped, he received no public office from Augustus except once being invested as an augur (an official Roman soothsayer). Under Tiberius, he held no office at all. Generally, he was considered an embarrassment at court. Under Caligula’s reign, he was granted a consulship as a colleague to the emperor himself (AD 37), but otherwise, he was treated very badly by Caligula (who was his nephew), suffering public disrespect and scorn from him at court.

‘Puppet’ Emperor

At the assassination of Caligula in January AD 41, Claudius fled to one of the apartments of the palace and hid behind one of the curtains. He was discovered by the praetorians and taken to their camp, where the two praetorian prefects proposed him to the troops, who hailed him emperor.

His being made emperor, despite his feebleness and having no military or even administrational experience at all, is most likely due to his being the brother of Germanicus, who had died in AD 19 and had been very popular with the soldiery. Besides that, he might have been deemed a possible puppet emperor, whom one could easily control, by the praetorians. The senate first considered the restoration of the republic, but faced with the praetorians’ decision, the senators fell in line and bestowed imperial power upon Claudius.

The physical and Mental state of Claudius

He was short and possessed neither natural dignity nor authority. He had a staggering walk, ’embarrassing habits’, and ‘indecent’ laugh, and when annoyed, he foamed disgustingly at the mouth, and his nose ran. He stammered and had a twitch. He was always ill until he became emperor. Then his health improved marvelously, except for attacks of stomachache, which he said even made him think of suicide.

In history and in the accounts of ancient historians, Claudius comes as a positive mishmash of conflicting characteristics: absent-minded, hesitant, muddled, determined, cruel, intuitive, wise, and dominated by his wife and his personal staff of freedmen. He was probably all of these things. His choice of women was no doubt disastrous. But he may well have had good reason to prefer the advice of educated and trained, non-Roman executives to that of potentially suspect aristocratic senators, even if some of those executives did use their influence to their own financial advantage.

The senate’s initial hesitation in granting him the throne was the source of much resentment by Claudius. Meanwhile, the senator disliked him for not being their free choice of ruler. So Claudius came to be the first Roman emperor in a line of many to follow who was not truly appointed by the senate but by the army’s men. He also came to be the first emperor who granted the praetorians a large bonus payment at his accession (15,000 sesterces per man), creating another ominous precedent for the future.

Claudius’ first actions in office marked him as an exceptional emperor. Though he needed to, for honor’s sake, deal with Caligula’s immediate assassins (they were sentenced to death), he did not begin a witch hunt. He abolished the treason trials, burned criminal records, and destroyed Caligula’s infamous stock of poisons. Claudius also returned many of Caligula’s confiscations. In AD 42, the first revolt against his rule took place, led by the governor of Upper Illyricum, Marcus Furius Camillus Scribonianus.

The First Rebellion Against Claudius

The attempt of rebellion got shut down easily before it ever really got started. However, it revealed that the instigators of the uprising had possessed connections with very influential nobility in Rome. The subsequent shock of just how close to his person such conspirators may be led the emperor to adopt stringent security measures. It is partly due to these measures that any of the six or more plots against the emperor during his twelve-year reign didn’t meet with success.

However, the suppression of such conspiracies cost the lives of 35 senators and over 300 equestrians. What a wonder that the Senate didn’t like Claudius! Immediately after the failed rebellion of AD 42, Claudius decided to distract any attention from such challenges to his authority by organizing a campaign to invade and conquer Britain. A plan close to the army’s heart, as they already once before had intended to do so under Caligula. – An attempt that had ended in a humiliating farce.

Fighting Hostile Britain

It was decided that Rome could no longer pretend that Britain did not exist, and a potentially hostile and possibly united nation just beyond the fringe of the existing empire presented a threat that could not be ignored. Also, Britain was famed for its metals; most of all tin, but gold was thought to be there. Besides, Claudius, for so long the butt of his family, wanted a piece of military glory, and here was a chance to get it. By AD 43, the armies stood ready, and all preparations for the invasion were in place. It was a formidable force, even by Roman standards. Overall, the command was in the hands of Aulus Plautius.

Plautius advanced but then got into difficulties. His orders were to do this if he met any sizable resistance. When he received the message, Claudius handed over the administration of the affairs of state to his consular colleague Lucius Vitellius and then himself took to the field. He went by river to Ostia and then sailed along the coast to Massilia (Marseilles). From there, traveling overland and by river transport, he reached the sea and crossed to Britain, where he met up with his troops, who were encamped by the river Thames.

Assuming command, he crossed the river, engaged the barbarians, who had rallied together at his approach, defeated them, and took Camelodunum (Colchester), the barbarian’s apparent capital. Then, he put down several other tribes, defeating them or accepting their surrender.

He confiscated the tribes’ weapons, which he handed over to Plautius with orders to subdue the rest. He then headed back to Rome, sending news of his victory ahead. When the senate heard about his achievement, it granted him the title of Britannicus and authorized him to celebrate a triumph through the city.

Claudius had been in Britain just sixteen days. Plautius followed up the advantage gained and was from AD 44 to 47 governor of this new province. When Caratacus, a royal barbarian leader, was finally captured and brought to Rome in chains, Claudius pardoned him and his family.

Claudius’s Military Actions in the East

In the east, Claudius also annexed the two client kingdoms of Thracia, making them into another province. Claudius also reformed the military. The granting of Roman citizenship to auxiliaries after a service of twenty-five years was introduced by his predecessors, but it was under Claudius that it truly became a regular system.

Were most Romans naturally intent on seeing the Roman empire as a solely Italian institution, Claudius refused to do so, allowing senators to be drawn also from Gaul. In order to do so, he revived the office of censor, which had fallen into disuse. However, such changes caused storms of xenophobia by the Senate and appeared only to support accusations that the emperor preferred foreigners to proper Romans.

With the help of his freedmen advisors, Claudius reformed the financial affairs of the state and empire, creating a separate fund for the emperor’s private household expenses. As almost all grain had to be imported, mainly from Africa and Egypt, Claudius offered insurance against losses on the open sea to encourage potential importers and to build up stocks against winter times of famine. Among his extensive building projects, Claudius constructed the port of Ostia (Portus), a scheme already proposed by Julius Caesar. This eased congestion on the river Tiber, but the sea currents gradually caused the harbor to silt up, which is why today it is no longer present.

Claudius also took great care in his function as a judge, presiding over the imperial law court. He instituted judicial reforms, creating in particular legal safeguards for the weak and defenceless. Of the loathed freedmen at Claudius’ court, the most notorious were perhaps Polybius, Narcissus, Pallas, and Felix, the brother of Pallas, who became governor of Judaea. Their rivalry did not prevent them from working in concert to their common advantage; it was virtually a public secret that honors and privileges were ‘for sale’ through their offices. But they were men of ability who rendered useful service when it was in their own interest to do so, forming a sort of imperial cabinet quite independent from the Roman class system.

The Betrayal of Valeria Messalina

It was Narcissus, the emperor’s minister of letters (i.e. he was the man who helped Claudius deal with all his matters of correspondence), who in AD 48 took the necessary actions when the emperor’s wife Valeria Messalina and her lover Gaius Silius attempted to overthrow Claudius when he was away at Ostia. Their intent was most likely to place Claudius’ infant son, Britannicus, on the throne, leaving them to rule the empire as regents.

Claudius was extremely surprised and appeared to have been indecisive and confused as to what to do. So it was Narcissus who took hold of the situation, had Silius arrested and executed, and Messalina driven into suicide. But Narcissus was not to benefit from having saved his emperor. In fact, it became the reason for his very downfall, as the emperor’s next wife Agrippina the younger, saw to it that the freedman Pallas, who was finance minister, soon eclipsed Narcissus’ powers.

Claudius is Dead, Long Live the Emperor Nero!

Agrippina was granted the title of Augusta, a rank no wife of an emperor had held before. And she was determined to see her twelve-year-old son Nero take the place of Britannicus as imperial heir. She successfully arranged for Nero to be betrothed to Claudius’ daughter, Octavia, and a year later, Claudius adopted him as his son.

Then, on the night of the 12 to 13 October AD 54, Claudius suddenly died. His death is generally attributed to his scheming wife Agrippina, who didn’t care to wait for her son Nero to inherit the throne and so poisoned Claudius with mushrooms.

People also ask:

What was Emperor Claudius famous for?

Claudius (full name Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus) was the fourth Roman emperor from 41 to 54 A.D. Best known for the successful expansion of Rome into Britain and parts of Africa and the Middle East.

What happened to Claudius the Roman emperor?

After marrying his niece Agrippina, Claudius adopted her son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (later the emperor Nero) to satisfy Agrippina’s lust for power, much to the disadvantage of his own son Britannicus. Roman tradition is unanimous: Claudius was poisoned by Agrippina on October 13, 54 CE, though the details differ.

How old was Claudius when he died?

Many authors contend that he was murdered by his own wife, Agrippina the Younger. After his death at the age of 63, his grand-nephew and legally adopted step-son, Nero, succeeded him as emperor.

What is the relationship between Claudius and Caligula?

The future emperor Claudius was Caligula’s paternal uncle. Caligula had two older brothers, Nero and Drusus, and three younger sisters, Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla, and Julia Livilla.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.