Last Updated on November 27, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: 159-121 BC

After the violent death of Tiberius Gracchus, the Gracchus family wasn’t finished yet.

Gaius Gracchus, a flamboyant and powerful public speaker, was to be a far more formidable political force than his brother.

The legacy of Tiberius Gracchus, the agrarian law, was being applied in a manner which created a fresh grievance among the allied regions of Italy. M.Fulvius Flaccus, one of the political supporters of Tiberius, suggested to grant them Roman citizenship as compensation for any disadvantages they should suffer from agrarian reform. This naturally was not popular, as the people holding Roman citizenship sought to keep it as exclusive as possible.

To get rid of Flaccus the senate sent him off as consul to Gaul to protect the Roman allies of Massilia who had appealed for help against the aggressive Celtic tribes. (The result of Flaccus operations should be the conquest of Gallia Narbonensis.)

But while Flaccus was absent, Gaius Gracchus, having finished his term of office as quaestor in Sardinia, returned to Rome to take the place of his brother. Being now some thirty years of age, nine years after his brother’s murder, Gaius was elected to the tribunate in 123 BC.

Flaccus now also returned in triumph from his Gallic victories.

The programme initiated by the younger Gracchus was wider in scope and much more far-reaching than that of his brother.

His reforms were wide-ranging and designed to benefit all interests, except of course those of Gracchus’ old enemies, – the senate.

He reaffirmed his brother’s land laws and established smallholdings in Roman territory abroad.

The new Sempronian Laws extended the operation of the agrarian laws and created new colonies. One of these new colonies was to be the first Roman colony outside of Italy, – on the old site of the destroyed city of Carthage.

The first of a series of open bribes to the voters was to enact legislation by which the population of Rome was to be provided with corn at half price.

The next measure struck straight at the power of the senate. Now members of the equestrian class should hold judgement in court cases over provincial governors accused of wrong-doings. It was a clear reduction in senatorial power as it restricted their power over the governors.

Yet further favour was granted to the equestrian class by awarding them the right to contract for the collecting of the enormous taxes due from the newly created province of Asia.

Further Gaius forced through huge expenditure on public works, such as roads and harbours, which once more mainly benefited the equestrian business community.

In 122 BC Gaius Gracchus was re-elected unopposed as ‘Tribune of the People’. Being that it had cost his brother his life to stand again for this office, it is remarkable to see how Gaius could remain in office without any major occurrence.

It appears that Gaius did not in fact stand again for the office of ‘Tribune of the People. He was far more reappointed by the popular assemblies, as the Roman commoners saw him as the champion of their cause.

Moreover, Flaccus was also elected as Tribune, granting the two political allies almost absolute power over Rome.

Gaius’ most visionary piece of legislation, however, was too far ahead of its time and failed to get passed even in the comitia tributa. The idea had been to grant all Latins full Roman citizenship and to bestow upon all Italians the rights so far enjoyed by the Latins (trade and intermarriage with Romans).

When Gaius Gracchus in 121 BC stood for yet another term as Tribune, the senate conspired to put forward their own candidate, M. Livius Drusus with an entirely false programme which was by its very nature simply designed to be yet more populist than anything Gracchus proposed.

This populist assault on Gracchus’ standing as a champion of the people, together with the loss of popularity resulting from the failed proposal to extend Roman citizenship and wild rumours and superstitions of curses circulating after a visit to Carthage by Gaius, led to his losing the vote for his third term in office.

Gaius Gracchus’ supporters, led by no lesser than Flaccus, held an angry mass demonstration on the Aventine Hill. Though some of them made the fatal mistake of carrying weapons.

The consul Lucius Opimius now proceded to the Aventine Hill to restore order. Not merely did he possess the high authority of his consular office, but he also was backed by a senatus consultum optimum, which was the order of the highest authority known to the Roman constitution. The order demanded him to take action against anyone endangering the stability of the Roman state. The bearing of weapos by some of Gracchus’ supporters was all the excuse Opimius needed. And there was little doubt that Opimius sought to bring about the end of Gaius Gracchus that night, for he was in fact the most prominent – and most bitter – rival of Gracchus and Flaccus.

What followed on the arrival of Opimius with a militia, legionary infantry and archers on the Aventine hill was in effect a massacre.

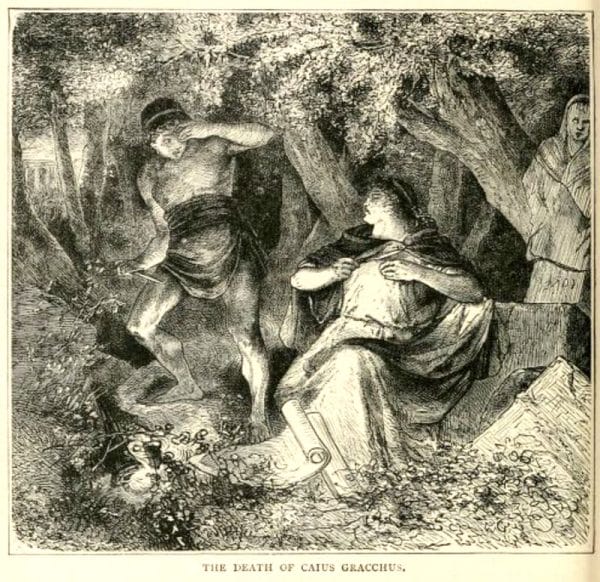

Gaius, realizing the situation hopeless ordered his personal slave to stab him to death. Following the massacre another 3’000 of Gracchus’ supporters are believed to have been arrested, taken to jail and strangled.

The brief emergence and demise of Tiberius Gracchus and of his brother Gaius Gracchus onto the scene of Roman politics should send shock waves through the entire structure of the Roman state; waves of such magnitude that their effects would be felt for generations.

One believes that around the time of the Gracchus brothers Rome began to think in terms of political right and left, dividing the two factions into optimates and populares.

However questionable their political tactics at times were, the brothers Gracchus were to show up a fundamental flaw in the way Roman society was conducting itself. Running an army with less and less conscripts to oversee an expanding empire was not sustainable. And the creation of ever greater numbers of urban poor was a threat to the stability of Rome itself.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.