Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD 15 – 69

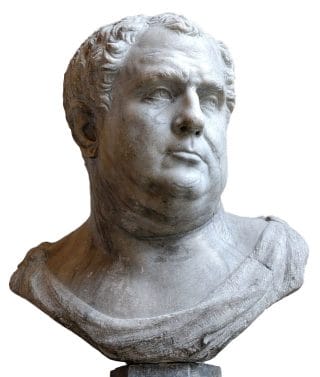

- Name: Aulus Vitellius

- Born on 24 September AD 15.

- Consul AD 48.

- Became emperor in AD 69.

- Married (1) Petronia (one son; Patronianus); (2) Galeria Fundana (one son; Vitellius; one daughter; Vitellia).

- Assassinated on 24 December AD 69.

Vitellius was born in AD 15. Vittelius’ father, Lucius Vitellius, three times held the office of consul as well as once being the emperor’s fellow censor.

Vitellius himself became consul in AD 48 and later became proconsul of Africa in about AD 61-2.

Vitellius was a man of some learning and knowledge of government but little military skill or experience. Therefore his appointment by Galba to his command in Lower Germany had taken most people by surprise. When Vitellius reached his troops in November AD 68 they were already considering rebellion against the loathed emperor Galba. In particular the German armies were still angry at Galba for refusing them a reward for their part in suppressing Julius Vindex. On 2 January AD 69, learning that the legions in Upper Germany had refused to swear allegiance to Galba, Vitellius’ men in Lower Germany, following the example of their commander Fabius Valens, hailed Vitellius emperor.

The army then set out for Rome, not led by Vitellius himself – for he possessed no knowledge of warfare – but by his generals Caecina and Valens.

They had already advanced 150 miles towards Rome when they learnt that Galba had been killed and Otho now had taken the throne. But they continued on undeterred. They crossed the Alps in March and then met Otho’s force near Cremona (Bedriacum) along the river Po.

The Danubian legions had declared for Otho and hence the weight of superior forces was on the emperor’s side. Though on the Danube those legions were useless to him, they had to march into Italy first. For now Otho’s side was still the lesser one. Caecina and Valens appreciated that if they would be successfully delayed by Othos’s forces they would lose the war.

So they devised a way by which to force a fight. They began the construction of a bridge which would lead them over the Po river into Italy. Otho was hence compelled to fight and his army was comprehensively defeated at Cremona 14 April AD 69.

Otho committed suicide on 16 April AD 69.

When learning of this news a joyous Vitellius set out for Rome, his voyage being seen by many as a endless decadent feast, not merely by him, but so, too, by his army.

The new emperor and his entourage entered Rome in brash triumph against the end of June. However, things remained peaceful. There were few executions and arrests. Vitellius even kept many of Otho’s officials in his administration, even granting amnesty to Otho’s brother Salvius Titianus, who had been a leading figure in the previous government.

All appeared as it should be as couriers arrived reporting the allegiance of the eastern armies. The legions having fought for Otho at Cremona also seemed to be accepting the new rule.

Vitellius rewarded his German legions by dispanding the praetorian guard as well as the urban cohorts of the city of Rome and offering the positions to them. This was generally seen as a very undignified affair, but then Vitellius was only on the throne due to the German legions. He knew that jsut as they had the power to make him emperor, they could turn on him, too. Hence he had little choice but to try and please them.

But such pampering of allies was not what truly made Vitellius unpopular. It was his extravagance and his triumphalism. Had Otho died a dignified death, then Vitellius comments on the ‘the sent of death of a fellow Roman being very sweet’ when visiting the battle field of Cremona (which was still littered with bodies at the time), did little to endear him to his subjects.

But so too his partying, entertaining and betting on the races offended the public.

To top it all, Vitellius, after taking the position of pontifex maximus (high priest) made a pronouncement about worship on a day which was traditionally regarded as unlucky.

Vitellius quickly gained a reputation as a glutton. He was said to eat three or four heavy meals a day, usually followed by a drinks party, to which he had himself invited to a different house each time. He was only able to consume this much by frequent bouts of self-induced vomiting. He was a very tall man, with a ‘vast belly’. On of his thighs was permanently damaged from being run over by Caligula’s chariot, when he had been in a chariot race with that emperor.

Had the initial signs of his taking power indicated he might enjoy a peaceful, though unpopular reign, things changed very quickly. Around the middle of July news already arrived that the armies of the eastern provinces had now rejected him. On 1 July they set up a rival emperor in Palestine, Titus Flavius Vespasianus, a battle-hardened general who enjoyed widespread sympathies among the army.

Vespasian’s plan was to hold Egypt while his colleague Mucianus, governor of Syria, led an invasion force to Italy. But things moved faster than either Vitellius or Vespasian had anticipated.

Antonius Primus, commander of the Sixth Legion in Pannonia, and Cornelius Fuscus, imperial procurator in Illyricum, declared their allegiance to Vespasian and led the Danube legions on an assault Italy. Their force comprised only five legions, about 30’000 men, and was only half of what Vitellius had in Italy.

But Vitellius could not count on his generals. Valens was ill. And Caecina, in a joint effort with the prefect of the fleet at Ravenna, attempted to change his allegiance from Vitellius to Vespasian (Though his troops did not obey him and instead arrested him).

As Primus and Fuscus invaded Italy, their force and that of Vitellius should meet almost at the same spot where the deciding battle for the throne had been fought some six months earlier.

The Second Battle of Cremona began on 24 October AD 69 and ended the next day in utter defeat for teh side of Vitellius.

For four days the victorious troops of Primus and Fuscus looted and burned the city of Cremona.

Valens, his health somewhat recovered, attempted to raise forces in Gaul to come to his emperor’s aid, but without success.

Vitellius made a limp attempt to hold the Appenine passes against Primus and Fuscus’ advance. However, the army he sent forth simply went over to the enemy without a fight at Narnia on 17 December.

Learning of this Vitellius tried to abdicate, hoping no doubt to save his own life as well as those of his family. Though in a bizarre move his supporters refused to accept this and forced him to return to the imperial palace.

In the mean time, Titus Flavius Sabinus, the elder brother of Vespasian, who was city prefect of Rome, on hearing of Vitellius’ abdication attempted, together with a few friends, to seize control of the city.

But his party was attacked by Vitellius’ guards and fled to the capitol. The follwing day, the capitol went up in flames, including the ancient temple of Jupiter – the very symbol of the Roman state. Flavius Sabinus and his supporters were dragged before Vitellius and put to death.

Only two days after these killings, on 20 December, the army of Primus and Fuscus fought its way into the city. Vitellius was carried to his wife’s house on the Aventine, from where he intended to flee to Campania. But at this crucial point he strangely appeared to change his mind, and returned to the palace.With hostile troops about to storm the place everyone had wisely deserted the building. So, all alone, Vitellius tied a money-belt around his waist and disguised himself in dirty clothes and hid in the door-keepers lodge, piling up furniture against the door to prevent anyone entering.

But a pile of furniture was a harldy a match for soldiers of the Danubian legions. The door was broken down a Vitellius was dragged out of the palace and through the streets of Rome. Half naked, he was hauled to the forum, tortured, killed and thrown into the river Tiber.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.