Last Updated on November 27, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

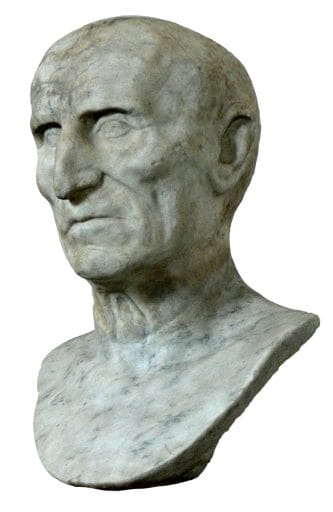

Life: 3 BC – AD 69

- Name: Servius Sulpicius Galba

- Born on 24 December 3 BC near Tarracina.

- Governor of Hispania Tarraconensis AD 61-68.

- Become emperor in AD 68.

- Married Lepida (two sons); all three died early in his career.

- Assassinated on 15 January AD 69.

Servius Sulpicius Galba was born on 24 December 3 BC, in a country villa near Tarracina, the son of patrician parents, Gaius Sulpicius Galba and Mummia Achaica.

Augusts, Tiberius, Caligula and Claudius all held him in great esteem and so he held successive offices as governor of Aquitania, consul (AD 33), military commander in Upper Germany, proconsul of Africa (AD 45).

He then made himself a enemy in Nero’s mother Agrippina the younger. And so, when she became Claudius’ wife in AD 49, he retired from political life for a decade. Shartly after Agrippina’s death he returned and in AD 60 was made governor of Hispania Tarraconensis.

Galba was an old disciplinarian whose methods owed much to cruelty, and he was notoriously mean.

He was almost completely bald and his feet and hands were so crippled by arthritis that he could not wear shoes, or even hold a book. Further, he had a growth on his left side, which could only be held in with difficulty by a kind of corset.

When in AD 68 Gaius Julius Vindex, the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis revolted against Nero, he did not intend to take the throne for himself, for he knew that he didn’t command widespread support. Far more he offered the throne to Galba.

At first Galba hesitated. Alas, the governor of Aquitania appealed to him, urging him to help Vindex. On 2 April AD 68 Galba took the great step at Carthago Nova and declared himself the ‘representative of the Roman people’. This didn’t lay claim to the throne, but it made him the ally of Vindex.

Galba was then joined by Otho, now the governor of Lusitania, and gilted husband of Poppaea. However, Otho had no legion in his province and Galba at that time only possessed control of one. Galba quickly began raising an additional legion in Spain. When in May AD 68 Vindex was defeated by the Rhine armies, a despairing Galba withdrew deeper into Spain. No doubt he saw his end coming.

However, roughly two weeks later news reached him that Nero was dead, – and that he had been pronounced emperor by the senate (8 June AD 68). The move also enjoyed the support of the praetorian guard.

Galba’s accession was notable for two reasons. It marked the end of what is known as the Julio-Claudian Dynasty and it proved that it was not necessary to be in Rome in order to win the title of emperor.

Galba moved into Gaul with some of his troops, where he received the first deputation from the senate in early July.

During the autumn Galba then disposed of Clodius Macer, who had risen against Nero in North Africa and most likely wanted the throne for himself.

But before Galba had even reached Rome, things began to start going wrong. Had the commander of the praetorian guard, Nymphidius Sabinus, bribed his men to abandon their allegiance to Nero, then Galba had always found the promised amount too high. So instead of honouring Nymphidius’s promise to the praetorians, Galba simply dismissed him and replaced him with a good friend of his own, Cornelius Laco. Nymphidius’ revolt against this decision was quickly put down and Nymphidius himself was killed.

Did the disposal of their leader not endear the praetorians to their new emperor, then the next move ensured that they hated him. The officers of the praetorian guard were all exchanged by favourites of Galba’s and, following this, it was announced that the original bribe promised by their old leader Nymphidius, was not to be reduced but simply not to be paid at all.

But not merely the praetorians, the regular legions, too, should not receive any bonus payment to celebrate a new emperor’s accession. Galba’s words were, “I choose my soldiers, I do not buy them.”

But Galba, a man of enormous personal wealth, soon displayed other examples of dire meanness. A commission was appointed to recover Nero’s gifts to many of the leading figures of Rome. His demands were that of the 2.2 billion sesterces Nero had given away, he wanted at least ninety percent to be returned.

This contrasted wildly with the blatant corruption among the officials Galba himself appointed. Many greedy and corrupt individuals in Galba’s new government soon destroyed any goodwill towards Galba which might have existed among the senate and the army.

The worst of these corrupt officials was said to be the freedman Icelus. He was no only rumoured to be Galba’s homosexual lover, but rumours told of him having stolen more in his seven months in office than all of Nero’s freedmen had embezzled in 13 years.

With this sort of government in Rome, it was not long before the army revolted against Galba’s rule. On 1 January AD 69 the commander of Upper Germany, Hordeonius Flaccus, demanded his troops to renew their oaths of allegiance to Galba. But the two legions based at Moguntiacum refused. They instead swore allegiance to the senate and the people of Rome and demanded a new emperor.

The very next day the troops of Lower Germany joined the rebellion and appointed their commander, Aulus Vitellius, as emperor.

Galba tried to create the impression of dynastic stability by adopting the thirty year-old Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus, as his son and successor. This choice however greatly disappointed Otho, one of the emperor’s very first supporters. Otho no doubt had hopes for the succession himself. Refusing to accept this setback, he conspired with the praetorian guard to rid himself of Galba.

On 15 January AD 69 several praetorians set upon Galba and Piso in the Roman Forum, murdered them and presented their severed heads to Otho in the praetorian camp.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.