Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD 86 – 161

- Name: Titus Aurelius Fulvus Boionus Arrius Antoninus

- Born on 19 September AD 86 at Rome.

- Consul AD 120, 139, 140, 145.

- Became emperor in 10 July AD 138.

- Wife: Annia Galeria Faustina ‘the elder’ (two sons; Marcus Aurelius, Marcus Galerius; two daughters; Aurelia Fadilla, Annia Galeria ‘the younger’).

- Died at Lorium, 7 March AD 161.

Titus Aurelius Fulvus Boionus Arrius Antoninus was born on 19 September AD 86 at Lanuvium (ca. 20 miles south of Rome). His family had long before come from the city of Nemausus (Nïmes) in southern Gaul, but for a long time since they had been a prominent and distinguished family at Rome.

Antoninus’ father, Titus Aurelius Fulvus, had held the office of consul once in AD 89, his grandfather had even held it twice.

As a boy Antoninus grew up at the family estate at Lorium in southern Etruria, roughly 10 miles to the west of Rome. He was raised first by his paternal grandfather, as his father died when he was still young. On the death of this grandfather, the maternal grandfather took charge of him.

Inheriting the walth of both his grandfathers made Antoninus one of the richest men in Rome.

He embarked on the traditional career for a senator, climbing the ladder of various offices, achieving the post of quaestor, then praetor and, alas, in AD 120 becoming consul under emperor Hadrian.

After this Hadrian chose him to be one of the four high judges who administered administered law in Italy.

Next he served as governor of the province of Asia, from AD 135 to 136.

Most likely on the basis of the very good reputation he had made for himself as governor of Asia, Antoninus, when he returned to Rome was made a member of the imperial council, a body of advisors to the emperor.

Despite his consulship and remarkable conduct as governor of Asia, Antoninus’ experience of government was fairly limited. More still he possessed no knowledge of any military matters whatsoever and, other than his stay in the province of Asia, he had never been beyond the borders of Italy.

So it was clearly his impressive person – honourable, sound and clearheaded – which won him the respect of the senate and the emperor.

Then, on his 62nd birthday (24 January AD 138) Hadrian, by now of failing health, announced he was to adopt Antoninus Pius. The adoption ceremony was held a month after, on 25 February AD 138. The ceremony revealed Hadrian’s plans for the empire. In adopting Antoninus, Hadrian just sought a safe pair of hands into which to trust the empire for the immediate future. But 51 years old at the time and childless, Antoninus was not to be the main aim of Hadrian’s intentions.

For the ceremony in which Hadrian adopted Antoninus, simultaeously had Antoninus adopt Marcus Annius Verus (Marcus Aurelius), Hadrian’s young nephew, and Lucius Ceionius Commodus, young son of the deceased Lucius Ceionius Commodus, who had been Hadrian’s first choice as heir.

If however Hadrian had thought that the relatively old Antoninus Pius would not reign for long before his death would hand power to the heirs he intended then he was wrong. For Antoninus was to live to the ripe old age of 74 (almost as old as Augustus), ruling longer than Trajan or Hadrian.

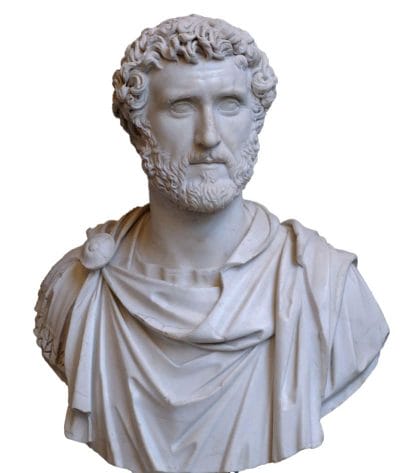

Following the example of Hadrian, Antoninus was also a bearded emperor.

Tall and handsome, physically strong, he possessed a calm and kind nature, though with a stern, aristocratic air.

He represented many of the virtues Roman sought in their emperor. An accomplished speaker, sound in morals, incorruptible by the temptations of easy living, not given to flaunt his wealth, he was dedicated to his duties.

Compared to his predecessors Antoninus was clearly not an ambitious emperor. But then he most likely understood himself as the custodian of an empire which was to be passed on to the young heirs chosen by Hadrian. And so he sought to maintain, rather than to make his own mark.

But there is no doubt that Antoninus possessed a willful, even determined side. For when he began to bend with old age, he wore a truss made of splints of lime wood, to allow him to walk erect. For evidently it was his decision that Romans should have an emperor who should walk upright.

Antoninus had no surviving sons. His only surviving daughter Faustina the younger eventually married Marcus Aurelius, further strengthening the succession intended by Hadrian.

The reason for the addition ‘Pius’ (meaning ‘dutiful’ or ‘respectful’) to his name is something which appears unclear even to the Roman historians. Several difference possibilities are known;

– he used to support his frail and elderly father-in-law with his arm when attentning the senate

– he pardonned those whom Hadrian embittered by ill-health had sentenced to death

– he insisted on great honours being bestowed on Hadrian, despite general opposition

– he guarded Hadrian agaisnt killing himself when the emperor despaired at his illness

– he was a truly compassionate and kind emperor who ruled with great care and moderation

At the death of Hadrian on 10 July AD 138, Antoninus’ succession to the throne was a seemless, peaceful event. Ther ewas no opposition. The officials of Hadrian’s government remained largely unchanged. Antoninus, if already respected before his accession, quickly won the goodwill of the senators, for being a moderate ruler, who was respectful of the ancient institution of the senate.

However, all should not go smoothly at first. Namely the deification of Hadrian which Antoninus demanded, was vehemently opposed. Hadrian had been unpopular, even hated. Worse still he had executed some senators.

But it was to be a battle of wills which Antoninus won. He clearly understood it as his duty to have divine status conferred upon the man, – his adoptive father ! – to whom he owed the throne. To have failed in this duty would not only have questioned the honour of Hadrian, but so too that of Antoninus himself.

And so, even if deeply unpopular and bitterly opposed by the senate at that early time of his reign, Antoninus’ reasons were still much understood and respected.

These initial problems behind him, Antoninus won renown for being a mild and compassionate ruler. He established new laws, protecting slaves from cruelty and abuse. During his reign two treason trials were conducted, yet not, like in previous reigns, blindly following the whims and allegations of an emperor, but according to law. Also Antoninus avoided any witch-hunts to find co-conspirators.

As a consequence to such a style of rule, Antoninus was a popular emperor.

Antoninus did not travel the empire like his predecessor, in fact he hardly ever left the capital at all during his 23-year rule. And if he left he would never move much further away from Rome than Campania or Etruria. He said, he worried for the expenses an emperor and his court might incur upon a province, if he chose to travel.

If Antoninus’ reign is much known for its peace and tranqulity, it is due to the calm of the man, rather than due to there being true peace along the borders of he empire.

Southern Scotland was conquered, with Hadrian’s wall being abandoned and a new defence – the Antonine Wall – being built ca. 40 miles further north.

Brigands caused trouble in Mauretania (AD 150), next trouble arose in Germany, an uprising took place in Egypt (AD 154), rebellions flared up in Judaea and Greece. Another rebellion arose in Dacia (AD 158) and conflicts ensued with the Alans.

But Antoninus was at times able to convince an opponent of the futility of war, merely by threatening it. Knowing of the renown of the Roman legions, he sent a letter to the king of Parthia, Vologaeses telling him of Rome’s willingness to intervene should he decide to attack Armenia. Vologaeses thougt better of it and dropped his plans for an attack.

Alas, Antoninus died after a very short illness in his sleep, having handed the reins of government to his adopted son Marcus Aurelius on that very day, 7 March AD 161.

Antoninus, died a very popular man and was deified by the senate without opposition.

His body was laid to rest in the Mausoleum of Hadrian, together with the body of his wife and sons, who had died much earlier.

Antoninus’ famous successor Marcus Aurelius paid this tribute to him: ‘Remember his qualities, so that when your last hour comes your conscience may be as clear as his.’

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.