Last Updated on November 27, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

Period: AD 96 – 192

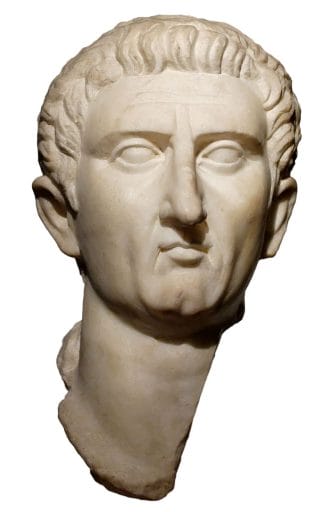

Marcus Cocceius Nerva – “Nerva”

Reign: AD 96 – 98

With the murder of Domitian there was no member of the Flavian house, much less one form the Julio-Claudian, left to succeed him. For once there was no ambitious general at the gates, and the senate could execute its constitutional authority.

So for the first time the senate made its own choice and appointed Marcus Cocceius Nerva. And the senators indeed chose well.

With Nerva, as well as with his four successors, there was a further break from tradition, as all four came from families which had long before settled out of Italy.

Nerva was in his sixties when he was pitch-forked into supreme power. He was not a born ruler of men, but he was a man of lofty character, wise and courageous. There was an immediate end of the grievances which had been growing up under Domitian. But he also faced facts and realized the fundamental weakness of the situation. An old man, he had no heir, and the power of the emperor rested with the army.

In the choice of his successor lay Rome’s destiny. Instead of leaving it to chance, faction or intrigue, Nerva took it upon himself to nominate a successor.

The very able now commanding on the Rhine was Marcus Ulpius Trajanus, like Nerva himself a provincial roman whose family had settled in Spain. In AD 97 Nerva adopted Trajan as his heir and associated the general with himself as co-emperor.

The choice was made acceptable by Trajan’s already high reputation, particularly among the army. It gave immediate security and ensured the undivided loyalty of the soldiery.

The nomination of Trajan was Nerva’s legacy to the empire, and in the next year, AD 98, he died.

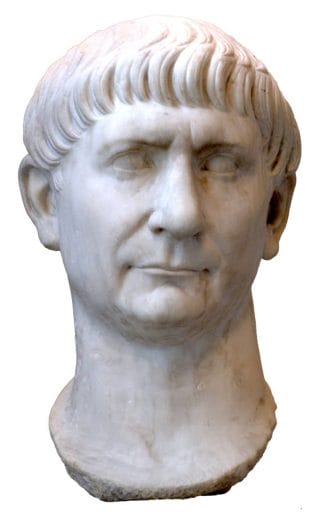

Marcus Ulpius Trajanus – “Trajan”

Reign: AD 98 – 117

Trajan, who was born at Italica near Seville in AD 52, became emperor in AD 98 and was thus of an age of considerable discretion.

He was most a man of high ability and character who had spent half his life in military service and enjoyed the trust of all who knew him.

The new emperor made no great haste to celebrate his accession.

His work on the Rhine had first to be completed, a work not of conquest but of strategic fortification. He was in any case more at home in a military camp than in the city.

Right at the beginning of his reign he established that the senate would always be kept informed about what was going on, and that the sovereign’s right to rule was compatible with freedom for those who were ruled.

Also he announced that during his during his reign no senator should be put to death.

When in due time he left his legions and came to Rome, the good impression was fully confirmed and he achieved immediate popularity by the frank simplicity and sincerity of his manners, and his fearless confidence in the loyalty of those who surrounded him.

the atmosphere of suspicion was allayed, the many informants and spies of previous reigns were substantially reduced.

Though Trajan found the finances in very bad order, he entirely declined to replenish the treasury by heavy taxation of by the usual arbitrary confiscations and fines. The need for economy was met by the cutting of extravagances in his own imperial household and in public departments. He further suppressed monopolies which helped develop trade and generally reformed the civil service, largely reducing corruption.

With increased revenue from trade came expenditure, especially on roads and ports, which again increased trade and revenue.

The result of all this was that no reign of the Roman empire left more splendid monuments of public wealth than that of Trajan, paid for without any undue pressure of taxation across the empire.

Great as the services rendered to the administration of the empire by Trajan were, he is more renowned for his achievements as a conqueror, since he was a soldier by instinct, whereas he was a emperor merely by circumstance.

Yet by common consent his military achievements were of no lasting advantage to the empire.

In pursuit of his aggressive military policies, Trajan carried the Roman army across the Danube in the campaigns of AD 101-106, and over the Euphrates in those of AD 114-117, discarding the principles recommended by Augustus.

Regarding the Dacian campaign it must be said that Trajan largely reacted due to a perceived threat from the Dacians. For twenty years previous to the war, the Dacian chief Decebalus had been welding the tribes of the Danube region into some sort of unity, had crossed the Danube itself and raided Roman territory, and had dealt with Domitian’s punitive expeditions in a fashion which clearly indicated that his forces were of considerable strength.

In AD 101 Trajan therefore organized his first Dacian expedition. The campaign was a hard-fought affair which demanded the utmost from the legions as well as from Trajan himself. Despite the very difficult terrain, Trajan forced his way through the pass known as the ‘Iron Gates’ and captured the Dacian capital, forcing Decebalus to submit.

Though no sooner was Trajan’s back turned, the Dacian diplomacy was at work again, building a new Danubian confederacy. So in AD 103 Trajan again took the field, determined to this time not merely assert Roman authority but crush the Dacians once and for all time. The Danube was spanned by a mighty bridge, the passes were forced at three different points simultaneously and Decebalus’ kingdom was destroyed in AD 104.

The newly conquered territory was settled largely with legionaries and in AD 106 Trajan returned to Rome to raise his forum and the monument known as Trajan’s Column. There were 123 days of public games and gladiatorial contests.

But by AD 113 affairs in the east again awakened his military ambitions.

The Euphrates had long been the vaguely acknowledged boundary between the Roman and Parthian dominions, but both empires claimed he northern kingdom of Armenia as a client state.

When the Parthian king Chosroes set up a king of his own on the throne of Armenia it was excuse enough for Trajan to begin a project of yet more military expansion.

In AD 113 he set his armies in motion and proceeded to the east to take command in person.

Chosroes tried to sue for piece, offering to set a new king in Armenia, a certain Parthamasiris, instead of the one Trajan initially took objection to, but it was not enough for the Roman emperor.

Trajan advanced meeting no resistance, till he reached the borders of Armenia. Parthamasiris came in person to plead for an end to hostilities, but only to be told that Armenia was no longer a kingdom but a Roman province, and that he should leave. The circumstances in which Parthamasiris was killed almost immediately after are obscure, but they certainly could not speak well for Trajan.

Armenia with Mesopotamia was secured, but Parthia was the emperor’s real objective. Operations however were delayed till AD 116 owing to the need for creating some organization, and then due to the havoc wrought by a terrific earthquake at Antioch, in which Trajan himself barely escaped with his life. Then came a great campaign over the Tigris, the passage of which in the face of an active foe was no easy task, and the advance to Susa, the last triumphant achievement.

For in the rear of the victorious armies revolt broke out in the annexed territories. Trajan was obliged to retreat with the enemy behind him, not in front of him, and his own health had at last broken down. He was indeed only checked, by no means defeated, but he saw at least that his dream of recreating the achievements of Alexander the Great could never be accomplished.

His health deteriorating rapidly he started on his way back home to Rome, but died on the way in Cilicia (AD 117), having left his chief-of-staff, Publius Aelius Hadrianus, in charge of the inconclusive situation in the east.

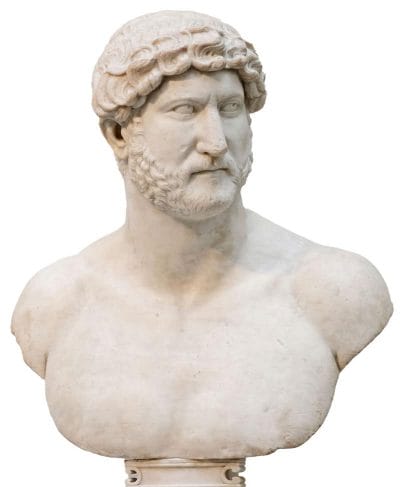

Publius Aelius Hadrianus – “Hadrian”

Reign: AD 117 – 138

Hadrian claimed that Trajan had adopted him on his deathbed: in any case he had already been acclaimed as emperor by the army in the east, and the senate had little choice but to confirm him in the post or risk civil war.

Hadrian was as complex as Trajan had been simple, of a type more readily associated with the Greek than with the Roman.

The statesman in Hadrian was swift to realize that for the Roman empire conquest was not statesmanship. With a frontier which could hold any attack at bay, nothing was to be feared from barbarians only half organized at their best.

Nothing was to be gained by defeating them in battle or occupying their territory. With the old boundaries the empire was large enough to tax the organizing abilities of any government to the utmost. Hadrian discarded all designs of expansion, and deliberately abandoned the recent conquests beyond the Euphrates.

Chosroes of Parthia, in whose place Trajan had set up a puppet of his own, was reinstated.

Having abandoned the recent acquisitions in the east Hadrian settled down to restore general order throughout the empire and to consolidate the administration at home.

Under Hadrian’s rule there was no depreciation of the majesty of Rome, but to him Rome meant the whole empire, not as to those before him, the imperial city.

The wall in Britain which bears Hadrian’s name, and of which portions still survive, is a monument to and a reminder of the role he took upon himself as ruler of an empire. It was in fact less of an empire as we understand, and more a collection of separate territories occupied by Roman troops and administered by Roman citizens according to Roman law. Because of distances, difficulties of communication, and widely differing circumstances, central government from Rome was well-nigh impossible, and provincial governors were largely left to their own devices. Hadrian, however, travelled tirelessly not only to all the provinces of Rome, but along most of their outer confines as well, and established boundary lines.

He was a man of wide learning, who, it was said, spoke Greek more fluently than Latin, was a patron of art, literature and education, and a benefactor of the needy poor. His liberal-mindedness, did not, however, extend to the Jews, whom he provoked into renewed revolt by forbidding Jewish practices, including circumcision, and by building a shrine to Jupiter on the site in Jerusalem where the ancient Jewish temple had stood before it was gutted and demolished by Titus. The rising under Simon Bar Kochba (d. AD 135) in AD 131, was surprisingly effective, and was only put down after Hadrian had transferred Sextus Julius Severus, governor of Britain, to the Judaean front as commander. If the account of the historian Dio Cassius is accurate, in order to stop the threat of further war, the Roman army destroyed fifty Jewish fortresses and 985 villages, and killed 580’000 men. The 82 year old Rabbi Akiba, and the other scholars and teachers who had supported Bar Kochba, were tortured and then executed.

Late in his life Hadrian showed ever greater signs of failing self-control and he began to display vindictiveness and cruelty. His first choice for a successor was Aelius Verus, a youth who had no particular qualifications other than a handsome person. Though he soon died, and Hadrian in his place adopted a senator of mature years and distinguished character, Titus Aurelius Antoninus. Hadrian though also demanded that Antoninus adopt Verus’ son Lucius, as well as a youth of the highest promise called Marcus Annius Verus, whom the world should come to remember as Marcus Aurelius.

Hadrian fell the victim of a disease which not only eventually killed him put also saw him suffer severe bouts of depression and mood swings, which may at least help to account for the capricious cruelty he displayed at the close of his reign.

A year after the adoption of Antoninus Hadrian died (AD 138).

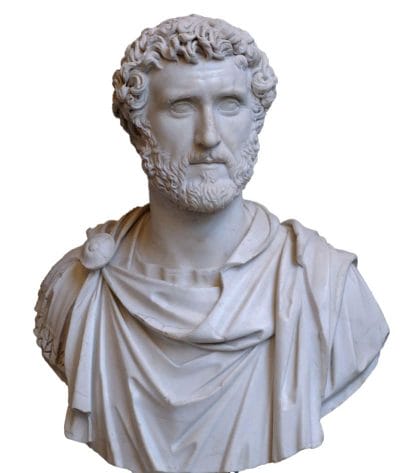

Titus Aurelius Fulvus Boionus Arrius Antoninus – “Antoninus Pius”

Reign: AD 138 – 161

At Hadrian’s death, once again, the childlessness of the emperor worked to the benefit of the state.

Antoninus Pius was not a man of great ambitions of his own and far more understood himself as a caretaker until the true choice of Hadrian, namely Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius, should succeed him to rule the empire.

The long rule of Antoninus Pius is almost recordless. On the barbarian frontiers occasionally military movements were inevitable, but even there Antoninus preferred conciliation to force. His was a reign of peace still more complete than that of his predecessor.

It is perhaps because Hadrian left the administration in such good order that the twenty-tree years of the reign of Antoninus, who died in AD 161, are remarkable for lack of incident. With the reports available to him from Hadrian’s globetrotting missions, Antoninus was able to spend most of his time at the centre of government in Rome. He did, however, make two adjustments to the frontiers of the empire. The eastern boundary of Upper Germany was advanced and strengthened; in Britain, a fortified turf wall, 60 km long, was built right across the country from the river Clyde to the Forth, some way north of Hadrian’s Wall. Though the Antonine Wall, built by the Second, Sixth and Twentieth legions, appears to have been abandoned, and perhaps dismantled, in about AD 165, Hadrian’s Wall stood firm until about AD 400, when the Romans withdrew from Britain.

In his lifetime Antoninus fully justified the honorific surname of Pius, bestowed on him by the senate: his death, unlike that of most other emperors, was appropriately calm and dignified.

Marcus Annius Verus – “Marcus Aurelius”

Reign: AD 161 – 180

Lucius Ceionius Commodus – “Lucius Verus”

Reign: AD 161 – 169

In contrast to Antoninus’ tranquil reign, his successor, Marcus Aurelius, had to spend most of his time in the field at the head of his armies, one of which brought back from an eastern campaign the most virulent plague of the Roman era, which spread throughout the whole empire.

A born student, Marcus Aurelius was called unwillingly by his overpowering sense of duty to be a man of action.

He was an active devotee of the Stoic school of philosophy, one of whose doctrines was the universal brotherhood and equality of man. when the time came, he insisted that equal imperial rights should be vested in his rival candidate, which were fully but largely nominally exercised by Verus until his death.

If fate had been kinder to Marcus Aurelius, his reign would have been a repetition of that of Antoninus. Obeying the call not of inclination but of duty, he had been constant in the practice of public functions whilst his heart was in the pursuit of philosophical truths.

The troops had known the vigour of Hadrian but had never felt the hand of the mild Antoninus, and the legions in distant Britain were eager to raise their own commander, Priscus, to the purple. But Priscus was too stoutly loyal to be tempted and the mutiny collapsed.

then in the east Parthia once more asserted her claim to Armenia. Parthian forces poured over the border and threatened Syria, a region always destructive to the discipline of the Roman garrison. Hadrian had everywhere maintained very strict discipline, Antoninus had no doubt neglected it. Now Roman prestige in the east was so threatened as to call for the emperor’s presence.

Marcus had no craving for the laurels of a conqueror and so left the command for the Parthian war to his imperial colleague Verus, who remained for the most part ingloriously in Antioch, one of the most luxurious cities of the empire.

The work of organizing and campaigning was carried out by subordinates who had been chosen for their efficiency. Priscus, who was summoned from Britain, and Cassius Avidius, a stern disciplinarian soldier.

But some five years of hard campaigning were needed before Parthia would submit to the terms by which she surrendered her claim to Mesopotamia and Armenia.

But the Parthian war was only a prelude, for yet greater violence was to follow. On the upper Danube the German Quadi and Marcomanni were threatening, and the return of Verus with the troops from the east was attended with a tremendous outbreak of plague in Italy which delayed the necessary preparations.

Marcus Aurelius was not free from the conviction that the disease was a visitation, a punishment sent by the gods for some flaw of sacrilege in the state. And to this superstition may well be attributed the severe persecution of the Christians who had enjoyed almost complete immunity under Hadrian and Antoninus.

In AD 167 Marcus took the field in company with Verus. The demonstration of force was enough to bring the Quadi to terms without fighting. In AD 168 the emperors were able to return home in peace, though Verus fell ill and died, leaving Marcus to reign on alone.

The peace on the Danube though proved a hopeful illusion.

Year after year of campaigning should follow of which the emperor would not spare himself, however much he disliked it, since he he understood it part of his duty. Though he was under no illusion as to his own very mediocre abilities as a general, and trusted more in the military judgement of his officers than in his own.

In AD 175 a unhappy revolt arose in which Cassius Avidius, believing Marcus Aurelius dead, declared himself emperor. Marcus reluctantly saw himself forced to move his troops to deal with a man he believed a loyal subject. Though news soon came that the rising had been put down and Cassius was dead. Understanding the tragedy Marcus insisted that Cassius’ family should stay unharmed and no-one should be punished.

It wasn’t long before he was called again to the Danube frontier. On this occasion his armies proved more convincingly successful than before and yet the campaign was not finished when he was struck down by sickness, and died in AD 180, worn out by his labours, sixty years of age.

Marcus Aurelius left to posterity the triumphal column in Rome which bears his name and records his victories over the Marcomanni (an inferior version of that of Trajan), and, rather unusually, a book of meditations, written in Greek. At his death in AD 180 at the age of 59, the empire was once again undergoing a period of general unease. As soon as one revolt was crushed or a barbarian invasion averted, another would break out, or threaten, in a different part of the empire.

Of Antoninus and Marcus Aurelius Edward Gibbon (an acclaimed British 18th century historian) wrote, “Their united reigns are possibly the only period in history in which the happiness of a great people was the sole object of government.”

Lucius Aurelius Commodus – “Commodus”

Reign: AD 180 – 192

The previous 84 years had seen just five emperors; during the next 104 years Rome should endure no less than 29. What really started the rot was that alone of the ‘five good emperors’, Marcus Aurelius had a son whom he had nominated as his successor. Marcus Aurelius had been 40 when he assumed the imperial purple gown of an office for which he had been groomed for more than twenty years. Lucius Aurelius Commodus had a number of elder brothers who had died early: he only 19 when he became emperor, and he proved to be a latter-day Nero.

He was an ill-conditioned youth whose education had been excellent though ineffective in practice

Was Commodus in effective command of the Danubian campaign on his accession, he made a inglorious peace with the barbarians, which confirmed the conviction of the hostile tribes that the day of Roman supremacy was indeed past – and returned to Rome to live a life of leisure leaving the administration in the hands of his tutors.

The personal character of the last two emperors compelled a respect and admiration which safeguarded them in spite of a gentleness that might be interpreted as weakness. The young Commodus though possessed neither force nor elevation of character nor intelligence. Plots were formed against him. They were discovered and suppressed. But he took alarm, and fear transformed him into a tyrant who alternated between raising worthless favourites to power and surrendering them to the enemies they excited.

Like Nero, his private life was a disgrace and his public extravagances outageous; like Nero, he fancied himself in the circus; and like Nero, he died an undignified death – a professional athlete was hired to strangle him in his bed in AD 192.

The High Point Chronology

- AD 96 Murder of Domitian. The senate elects Nerva emperor.

- 97 Nerva adopts Trajan as colleague and successor

- 98 Death of Nerva. Trajan sole emperor. Trajan completes military organization on the Rhine and returns to Rome.

- 101 Trajan’s first campaign on the Danube

- 102 Trajan forces the ‘Iron Gates’ and penetrates Dacia

- 104 Conquest of Dacia and death of Dacian King Decebalus.

- 106 Erection of the Forum and Column of Trajan in Rome. Colonization of Dacia. The Nabatean kingdom of Petra is annexed as the province of Arabia.

- 114 Trajan advances against Parthia

- 114-117 Parthian War. Roman victory brings Armenia, Mesopotamia and Assyria as new provinces into the Empire

- 114-118 Revolt of the Jews in Cyrenaica, Egypt and Cyprus

- 115 Trajan crosses the Tigris

- 116 Trajan captures Ctesiphon, but insurrections in his rear force him to retire.

- 117 Trajan dies at Selinus in Cilicia. Hadrian emperor. Hadrian reverts to policy of non-expansion, and makes peace with Parthia.

- 118 Partial withdrawal from Dacia

- 121-125 First voyages of Hadrian: Gaul, Rhine frontiers, Britain (122, Hadrian’s Wall erected in northern England), Spain, western Mauretania, the Orient, and Danube provinces

- 128-132 Second voyage of Hadrian: Africa, Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, Cyrene

- 131 Hadrian at Alexandria

- 133 Last organized revolt of the Jews under Bar Kochba and their final dispersion

- 134 Hadrian at Rome

- 135 Hadrian nominates Verus as successor

- 137 Verus dies

- 138 Hadrian adopts Antoninus. Antoninus adopts Marcus Aurelius. Death of Hadrian. Antoninus emperor.

- 138-161 Antoninus Pius emperor. Pursues policy of domestic reforms, centralised administration, better relations with Senate, though there is unrest in the provinces. Gradual rise of power of the barbarians along imperial borders.

- 141-143 Hadrian’s Wall extended into Scotland

- 161 Death of Antoninus. Marcus Aurelius emperor. Marcus Aurelius makes Verus co-emperor.

- 162-166 Parthian War

- 165 Verus takes official command of the east.

- 166 Unrest in the upper and middle Danube frontiers, where Quadi and Marcomanni in movement. Outbreak of plague. Religious revival. Severe persecution of Christians.

- 167-175 First Marcomannic War

- 167 Marcus Aurelius and Verus march against the Quadi who seek and obtain peace.

- 168 Death of Verus. Marcus Aurelius sole emperor.

- 169-179 Campaigns of Marcus Aurelius in Pannonia

- 175 Revolt of Avidius Cassius, who is put to death by his own followers

- 175-180 Second war against Danube-Germans

- 177 Marcus Aurelius makes Commodus co-emperor

- 180 Death of Marcus Aurelius. Accession of Commodus. Commodus makes peace with the Sarmatians and returns to Rome.

- 183 Plot to kill Commodus discovered. Henceforth he acts as panic-stricken tyrant Power of favourite Perennis.

- 186 Fall of Perennis. Power of Cleander

- 189 Fall of Cleander

- AD 192 Death of Commodus

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.