Last Updated on July 23, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD 15 – 68

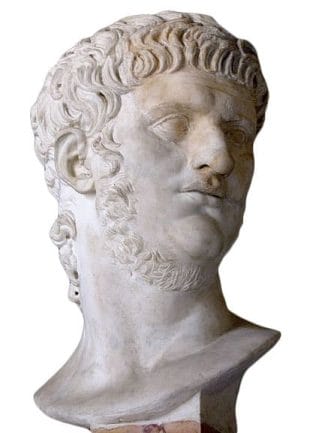

- Name: Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus

- Born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus at Antium in AD 37

- Son of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, consul in AD 32, and Agrippina, sister of Caigula, who then married Crispus Passienus and, later, in AD 49, her uncle Claudius.

- Became emperor in AD 54.

- Married (1)Octavia; (2) Poppaea Sabina (one daughter, Claudia Augusta, who died in infancy); (Statilia Messalina.

- Committed suicide in AD 68.

Nero Early Life

Nero was born at Antium (Anzio) on 15 December AD 37 and was first named Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He was the son of Cnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, who was descended from a distinguished noble family of the Roman Republic (a Domitius Ahenobarbus is known to have been consul in 192 BC, leading troops in the war against Antiochus alongside Scipio Africanus), and Agrippina the younger, who was the daughter of Germanicus.

When Nero was two, his mother was banished by Caligula to the Pontian Islands. His inheritance was then seized when his father died one year later.

With Caligula killed and a milder emperor on the throne, Agrippina (who was emperor Claudius’ niece) was recalled from exile and her son was given a good education. Once in AD 49 Agrippina married Claudius, the task of educating of the young Nero was handed to the eminent philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca.

Further to this Nero was betrothed to Claudius’ daughter Octavia.

In AD 50 Agrippina persuaded Claudius to adopt Nero as his own son. This meant that Nero now took precedence over Claudius’ own younger child Britannicus. It was at his adoption that he assumed the name Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus. These names were clearly largely in honor of his maternal grandfather Germanicus who had been an extremely popular commander with the army. Evidently, it was felt that a future emperor was well advised to bear a name that reminded the troops of their loyalties. In AD 51 he was named heir-apparent by Claudius.

Alas in AD 54 Claudius died, most likely poisoned by his wife. Agrippina, supported by the prefect of the praetorians, Sextus Afranius Burrus, cleared the way for Nero to become emperor. Since Nero was not yet seventeen years old, Agrippina the Younger first acted as regent. A unique woman in Roman history, she was the sister of Caligula, the wife of Claudius, and the mother of Nero.

But Agrippina’s dominant position did not last for long. Soon she was shunted aside by Nero, who sought not to share power with anyone. Agrippina was moved to a separate residence, away from the imperial palace and from the levers of power. When on 11 February AD 55 Britannicus died at a dinner party in the palace – most likely poisoned by Nero, Agrippina was said to have been alarmed. She had sought to keep Britannicus in reserve, in case she should lose control of Nero.

Nero was fair-haired, with weak blue eyes, a fat neck, a pot belly, and a body that smelt and was covered with spots. He usually appeared in public in a sort of dressing gown without a belt, a scarf around his neck, and no shoes.

In character he was a strange mix of paradoxes; artistic, sporting, brutal, weak, sensual, erratic, extravagant, sadistic, bisexual – and later in life almost certainly deranged.

But for a period the empire enjoyed sound government under the guidance of Burrus and Seneca.

Nero announced he sought to follow the example of Augustus’ reign. The senate was treated respectfully and granted greater freedom, the late Claudius was deified. Sensible legislation was introduced to improve public order, reforms were made to the treasury, and provincial governors were prohibited from extorting large sums of money to pay for gladiatorial shows in Rome.

Nero himself followed in the steps of his predecessor Claudius in applying himself rigorously to his judicial duties.

He also considered liberal ideas, such as ending the killing of gladiators and condemning criminals in public spectacles.

In fact, Nero, most likely largely due to the influence of his tutor Seneca, came across as a very humane ruler at first. When the city prefect Lucius Pedanius Secundus was murdered by one of his slaves, Nero was intensely upset that he was forced by law to have all four hundred slaves of Pedanius’ household put to death.

It was no doubt such decisions that gradually lessened Nero’s resolve for administrative duties and caused him to withdraw more and more, devoting himself to such interests as horse racing, singing, acting, dancing, poetry and sexual exploits.

Seneca and Burrus tried to guard him against too greater excesses and encouraged him to have an affair with freedwoman named Acte, provided that Nero appreciated that marriage was impossible. Nero’s excesses were hushed up, and between the three of them they successfully managed to avert continued attempts by Agrippina to exert imperial influence.

Agrippina meanwhile was outraged at such behaviour. She was jealous of Acte and deplored her son’s ‘Greek’ tastes for the arts.

But when news reached Nero of what angry gossip she was spreading about him, he became enraged and hostile toward his mother.

The turning point came largely through Nero’s inherent lust and lack of self-control, for he took, as his mistress the beautiful Poppaea Sabina. She was the wife of his partner in frequent exploits, Marcus Salvius Otho. In AD 58 Otho was dispatched to be governor of Lusitania, no doubt to move him out of the way.

Agrippina, presumably seeing the departure of Nero’s apparent friend as an opportunity to reassert herself, sided with Nero’s wife, Octavia, who naturally opposed her husbands affair with Poppaea Sabina.

Nero angrily responded, according to the historian Suetonius, with various attempts on his mother’s life, three of which were by poison and one by rigging the ceiling over her bed to collapse while she would lay in bed. Therafter even a collapsible boat was built, which was meant to sink in the Bay of Naples. But the plot only succeeded in sinking the boat, as Agrippina managed to swim ashore. Exasperated, Nero sent an assassin who clubbed and stabbed her to death (AD 59).

Nero reported to the senate that his mother had plotted to have him killed, forcing him to act first. The senate didn’t appear to regret her removal at all. There had never been much love lost by the senators for Agrippina.

Nero celebrated by staging yet wilder orgies and by creating two new festivals of chariot-racing and athletics. He also staged musical contests, which gave him further chance to demonstrate in public his talent for singing while accompanying himself on the lyre. In an age when actors and performers were seen as something unsavoury, it was a moral outrage to have an emperor performing on stage. Worse still, Nero being the emperor, no one was allowed to leave the auditorium while he was performing, for whatever reason. The historian Suetonius writes of women giving birth during a Nero recital, and of men who pretended to die and were carried out.

In AD 62 Nero’s reign should change completely. First Burrus died from illness. He was succeeded in his position as praetorian prefect by two men who held the office as colleagues. One was Faenius Rufus, and the other was the sinister Gaius Ofonius Tigellinus.

Tigellinus was a terrible influence on Nero, who only encouraged his excesses rather than trying to curb them. And one of Tigellinus first actions in office was to revive the hated treason courts.

Seneca soon found Tigellinus – and an ever-more willful emperor – too much to bear and resigned. This left Nero totally subject to corrupt advisers. His life turned into little else but a series of excesses in sport, music, orgies and murder. In AD 62 he divorced Octavia and then had her executed on a trumped-up charge of adultery. All this to make way for Poppaea Sabina whom he married. (But then Poppaea too was later killed. – Suetonius says he kicked her to death when she complained at his coming home late from the races.)

Had his change of wife not created too much of a scandal, Nero’s next move did. Until then he had kept his stage appearances to private stages, but in AD 64 he gave his first public performance in Neapolis (Naples). – Romans saw it indeed as a bad omen that the very theatre Nero had performed in shortly after was destroyed by an earthquake.

Within a year the emperor made his second appearance, this time in Rome. The senate was outraged.

And yet still the empire enjoyed moderate and responsible government by the administration. Hence the senate was not yet alienated enough to overcome its fear and do something against the madman whom it knew on the throne.

Then, in July AD 64, the Great Fire ravaged Rome for six days. The historian Tacitus, who was about 9 years old at the time, reports that of the fourteen districts of the city, ‘four were undamaged, three were utterly destroyed and in the other seven there remained only a few mangled and half-burnt traces of houses.’

This is when Nero was famously to have ‘fiddled while Rome burned’. This expression however appears to have its roots in the 17th century (alas, Romans didn’t know the fiddle).

The historian Suetonius describes him singing from the tower of Maecenas, watching as the fire consumed Rome. Dio Cassius tells us how he ‘climbed on to the palace roof, from which there was the best overall view of the greater part of the fire and, and sang ‘The capture of Troy”

Meanwhile Tacitus wrote; ‘At the very time that Rome burned, he mounted his private stage and, reflecting present disasters in ancient calamities, sang about the destruction of Troy’.

But Tacitus also takes care to point out that this story was a rumour, not the account of an eye witness.

If his singing on the roof tops was true or not, the rumour was enough to make people suspicious that his measures to put out the fire might not have been genuine. To Nero’s credit, it does indeed appear that he had done his best to control the fire.

But after the fire he used a vast area between the Palatine and the Equiline hills, which had been utterly destroyed by the fire to build his ‘Golden Palace’ (‘Domus Aurea’). This was a huge area, ranging from the Portico of Livia to the Circus Maximus (close to where the fire was said to have started), which now was turned into pleasure gardens for the emperor, even an artificial lake being created in its centre. The temple of the deified Claudius was not yet completed and – being in the way of Nero’s plans, it was demolished.

Judging by the sheer scale of this complex, it was obvious it could never have been built, were it not have been for the fire. And so quite naturally Romans had their suspicions about who had actually started it.

It would be unfair however to omit that Nero did rebuild large residential areas of Rome at his own expense. But people, dazzled by the immensity of the Golden Palace and its parks, nonetheless remained suspicious.

Nero, always a man desparate to be popular, therefore looked for scapegoats on whom the fire could be blamed. He found it in an obscure new religious sect, the Christians.

And so many Christians were arrested and thrown to the wild beasts in the circus, or they were crucified . Many of them were also burned to death at night, serving as ‘lighting’ in Nero’s gardens, while Nero mingled among the watching crowds.

It is this brutal persecution which immortalized Nero as the first Antichrist in the eyes of the Christian church. (The second Antichrist being the reformist Luther by edict of the Catholic Church.)

Meanwhile Nero’s relation’s with the senate deteriorated sharply, largely due to the execution of suspects through Tigellinus and his revived treason laws.

Then in AD 65 there was a serious plot against Nero. Known as the ‘Pisonian Conspiracy’ it was led by Gaius Calpurnius Piso. The plot was uncovered and nineteen executions and suicides followed, and thirteen banishments. Piso and Seneca were among those who died.

There was never anything even resembling a trial: people whom Nero suspected or disliked or who merely aroused the jealousy of his advisers were sent a note ordering them to commit suicide.

Nero, leaving Rome in charge of the freedman Helius, went to Greece to display his artistic abilities in the theatres of Greece. He won contests in the Olympic Games, – winning the chariot race although he fell of his chariot (as obviously nobody dared to defeat him), collected works of art, and opened a canal, which was never finished.

Alas, the situation was becoming very serious in Rome. The executions continued. Gaius Petronius, man of letters and former ‘director of imperial pleasures’, died in this manner in AD 66. So did countless senators, noblemen, and generals, including in AD 67 Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, hero of the Armenian wars and supreme commander in the Euphrates region.

Further, a food shortage caused great hardship. Eventually Helius, fearing the worst, crossed over to Greece to summon back his master.

By January AD 68 Nero was back in Rome, but things were now too late. In March AD 68 the governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, Gaius Julius Vindex, himself Gallic-born, withdrew his oath of allegiance to the emperor and encouraged the governor of northern and eastern Spain, Galba, a hardened veteran of 71, to do the same. Vindex’ troops were defeated at Vesontio by the Rhine legions who marched in from Germany, and Vindex committed suicide. However, thereafter these German troops, too, refused to furthermore recognize Nero’s authority. So too Clodius Macer declared against Nero in north Africa.

Galba, having informed the senate that he was available, if required, to head a government, simply waited.

Meanwhile in Rome nothing was actually done to control the crisis.

Tigellinus was seriously ill at the time and Nero could only dream up fantastic tortures which he sought to inflict on the rebels once he had defeated them. The praetorian prefect of the day, Nymphidius Sabinus, persuaded his troops to abandon their allegiance to Nero. Alas, the senate condemned the emperor to be flogged to death.

As Nero heard of this he chose rather to commit suicide, which he did with the assistance of a secretary (9 June AD 68).

His last words were, “Qualis artifex pereo.” (“What an artist the world loses in me.”)

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.