Last Updated on December 17, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

The Battle of Adrianople on 9 August AD 378 was the beginning of the end for the Roman empire.

Was the Roman empire weakening, then the barbarians were on the rise. Rome was no longer in its prime, yet it still could muster a tremendous force.

The western empire at the time was ruled by Gratian, meanwhile in the east was ruled by his uncle Valens.

Out in the barbarian wilderness the Huns were driving westwards, destroying the Gothic realms of the Ostrogoths and the Visigoths. In AD 376 Valens made the momentous decision to allow the Visigoths to cross the Danube and settle in imperial territory along the Danube.

However, he failed to assure that the new arrivals in the empire were properly treated.

Mistreated and exploited by provincial officials and governors it was only a matter of time until the Visigoths rose in rebellion, threw off Roman rule and ran amok within imperial territory.

Once they did they were soon joined by their former neighbours the Ostrogoths who crossed Danube and drove into the area ravaged by the Visigoths.

Valens hurried back from his war with the Persians after learning that the combined forces of the Goths were rampaging through the Balkans.

But the Gothic forces were so large, he found it wiser to ask Gratian to join him with the western army in order to deal with this massive threat. However Gratian was delayed. He claimed it was the everlasting trouble with the Alemanni along the Rhine which held him up. The easterners however slaimed it was his reluctance to help, which caused the delay. But alas, Gratian did eventually set out with his army toward the east.

But – in a move which has astounded historians ever since – Valens decided to move against the Goths without waiting for his nephew to arrive.

Perhaps the situation had grown so dire, he felt he could wait no longer. Perhaps though he didn’t want to share the glory of defeating the barbarians with anyone.

Mustering with a force over 40’000 strong, Valens may well have felt very confident of victory. The combined Gothic forces however were massive.

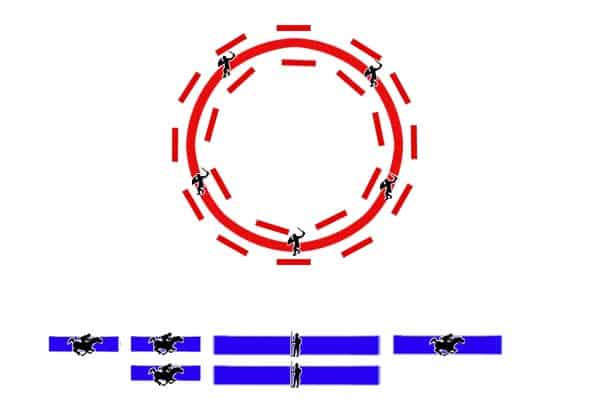

1. Valens draws up his army

Valens arrived to find the main Gothic camp, a circular encampment, called ‘laager’ by the Goths, with carts acting as a palisade.

He drew up his force in a fairly standard formation and began to advance.

However, at this point the main Gothic cavalry force was not present. It was at a distance making use of better grazing grounds for the horses.

Valens may well have believed the Gothic cavalry was away on a raid. If so, it was a disastrous mistake.

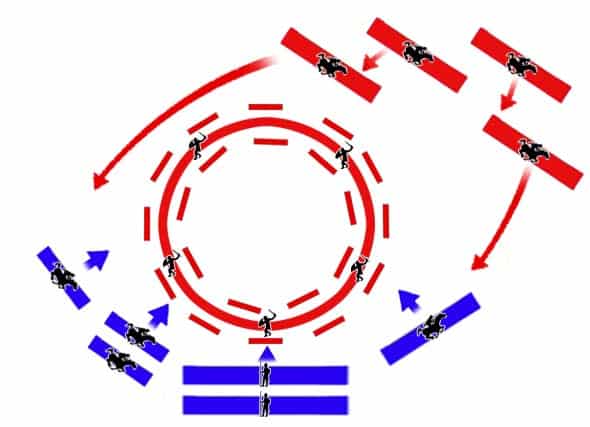

2. Valens attacks, the Gothic cavalry arrives

Valens now made his move, committing himself completely to the assault on the ‘laager’.

Perhaps he was hoping to crush the ‘laager’ before any relief could arrive from the Gothic cavalry force. If that was his thinking, then it was a serious miscalculation.

For the Gothic heavy cavalry, having by now received warning from the embattled ‘laager’, soon after arrived on the scene.

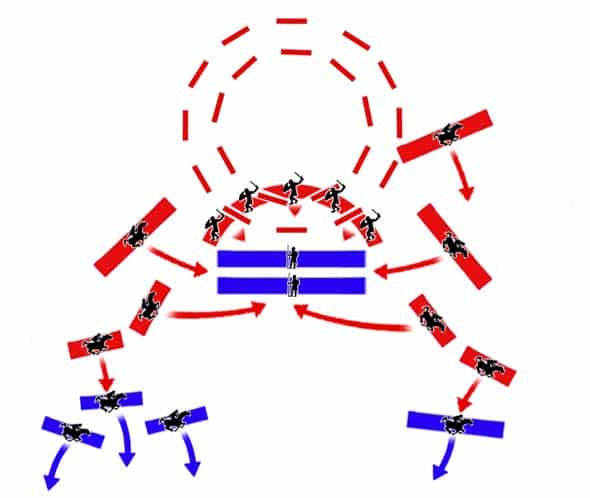

3. Roman Collapse

The arrival of the Gothic cavalry changed everything. The Roman light cavalry was no match for more heavily equipped Gothic horsemen. And so the Roman horse was simply swept off the field.

Some cavalrymen within the camp itself now took to their horses and joined their comrades. The Gothic infantry now saw the tide turning, abandoned its defensive position and began to advance.

No doubt by this time emperor Valens must have realized himself in dire trouble. However, a heavy infantry force of such size, endowed with Roman discipline, normally should have been able to extract itself from critical circumstances and retire in some fashion. Although losses would no doubt still have been severe.

But for the first time in a major contest (with the remarkable exception of Carrhae) a cavalry force proved itself the complete master of the Roman heavy infantry. The infantry stood little chance against assault by the heavy Gothic cavalry.

Attacked from all sides, reeling under the everlasting impacts of the Gothic cavalry charges, the Roman infantry fell into disarray and alas collapsed.

Emperor Valens was killed in the fighting. The Roman force was annihilated, accounts suggesting 40’000 dead on their side may well not be an exaggeration.

The Battle of Adrianople marks the point in history where the military initiative passed to the barbarians and should never be truly be regained again by Rome.

In military history it also represents the end of the supremacy of heavy infantry on the battle field. The case had been proven that a heavy cavalry force could utterly dominate the battle field. The eastern empire did partially recover from this disaster under emperor Theodosius. This emperor however drew his conclusions from this fateful battle and hence relied much on cavalry mercenaries in his army.

And it was with his use of the Germanic and Hunnic cavalry that he should eventually defeat the western legionary forces in civil wars to remove usurpers in the west, proving the point that power now lay no longer with the legions but with the horsemen.

Valens’ greatest mistake no doubt was not to wait for emperor Gratian and the western army. Yet even if he would have done so and been victorious, it might only have delayed a similar defeat for a time. The nature of warfare had changed. And the Roman legion was in effect obsolete.

And so the Battle of Adrianople was a key moment in world history, where power shifted. The empire continued on for some time but the tremendous losses suffered at this battle were never recovered.

The alternative View of the Battle of Adrianople

The battle of Adrianople is undisputedly a turning point in history, because of the scale of Rome’s defeat. However, it is worth pointing out that not everyone subscribes to the above description of the battle. The above interpretation is largely based on the writings of Sir Charles Oman, a famous 19th century military historian.

There are those who don’t necessarily accept his conclusion that the rise of heavy cavalry brought about a change in military history and helped overthrow the Roman military machine.

Some explain the Roman defeat at Adrianople simply as follows; the Roman army was no longer the deadly machine it had been, discipline and morale were no longer as good, Valens’ leadership was bad. The surprising return of the Gothic cavalry was too much to cope with for the Roman army, which was already fully deployed in battle, and hence it collapsed.

It was not any effect of heavy Gothic cavalry which changed the battle in the barbarians’ favour. Far more it was a breakdown of the Roman army under the surprise arrival of additional Gothic forces (i.e. the cavalry). Once the Roman battle order was disrupted and the Roman cavalry had fled it was largely down to the two infantry forces to battle it out among each other. A struggle which the Goths won.

The historic dimension of Adrianople in this view of events restricts itself solely to the scale of the defeat and the impact this had on Rome. Oman’s view that this was due to the rise of heavy cavalry and therefore represented a key moment in military history is not accepted in this theory.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.