Last Updated on December 13, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Had Roman involvement in Illyria and the Macedonian alliance with Carthage in the Second Punic War (right after Cannae!) not made Rome and Macedon the best of friends, then peace of 205 BC was destined not to last.

Rome suspiciously watched its neighbour across the sea. Philip V of Macedon sought supremacy over the Greeks, who requested help.

No doubt confident after their defeat of Carthage in 202 BC, Rome now deemed it best to remove the Macedonian threat as soon as possible. The pleas by Greek city states for assistance were all the excuse they needed to intervene in 200 BC, beginning the Second Macedonian War.

In 198 BC command passed into the hands of Titus Quinctius Flaminius. Had the previous Roman efforts led to nothing much, then things took a decisive turn with the arrival of Flaminius. He pushed on and finally managed to force a battle at the hills called Cynoscephalae.

Both sides were roughly equally matched, mustering about 25’000 men each. But both sides employed different systems, the Romans used the legionary method which had brought them victory over Carthage, the Macedonians fought in the Greek phalanx, which had under Alexander the Great defeated the Persians.

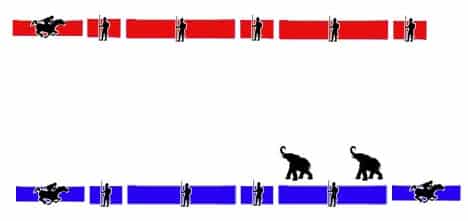

1. The Armies start the day either side of the Cynoscephalae

The armies closed on each other from either side of the chain of hills called Cynoscephalae. Both armies then made camp and spent the night on their side of the hills.

In the morning both sides found the hills covered in dense mist, making visibility poor.

The Macedonian king Philip was the first to send out a party to take control of the top of the hill chain in order to gain an advantage.

When Flaminius also sent out a small force they found the Macedonian party already atop the pass between the two main hills. Clearly at a disadvantage the Romans suffered losses in the following skirmish and sent message for help. Once Flaminius had sent some reinforcements up the mist-covered hill, then the Romans began to gain the upper hand.

But the mist-covered skirmish escalated further, as Philip then sent more reinforcements up his side of the hill, once more driving the Romans back off the pass.

Had all the fighting so far been skirmishing, then it is at this point that both armies finally set out to do battle.

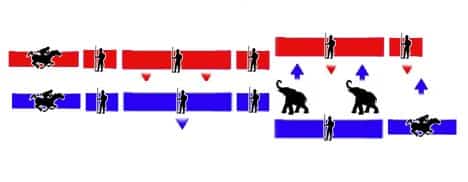

2. The Phalanx attacks, the Roman right advances

The skirmishing had caused Philip to hold the advantage of the higher ground.

However it was the Macedonian center and right wing which held the heights, their left was still marching up the hill. This break in the Macedonian line was to prove a fatal flaw. With the Macedonian left nowhere to be seen, Flaminius ordered his right to stay at the bottom of the slope.

As the Romans brought up their forces to meet the enemy at the pass, Philip simply ordered his phalanx to level their spears and attack. With such heavily armoured infantrymen bearing down on them, there was little Romans could do, as they began to take losses and were forced back.

The phalanx being the evidently superior force in the contest so far, Flaminius needed to act fast, if his left was not simply to be crushed by the Macedonian advance. He took control of his army’s right and advanced rapidly, hoping to divert some of Philip’s main force to the aid of the left wing. With elephants leading the way, the Roman troops rushed up the hill, trying to save the day. They met the Macedonian left which had only just reached the summit of the hill and was not yet in proper formation .

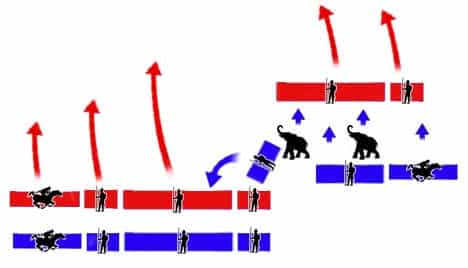

3. The Macedonian left driven back, small Roman force wheels around into enemy’s rear

If the Macedonian left was being forced back by the Roman advance, then the main contest was beyond doubt still being fought between the heavy Macedonian infantry and the Roman left.

A single military tribune on the Roman right now acted on his own. He broke away with a force of 20 maniples and swung them around into the rear of the Macedonian heavy infantry in the centre.

This decisive action caused chaos among the Macedonians. Their battle order fell apart, many fled, others simply surrendered.

In essence the victory at Cynoscephalae was the triumph of the Roman legionary system over the Greek phalanx. The phalanx was a superb force when meeting its enemy head-on. This can be clearly seen in the fact that the Roman right stood little chance against Philip’s heavy infantry as it advanced.

As the Macedonian wall of shields, with thousands of 20 foot (ca. 6 metres) lances protruding from it, came down the hill, there was little to nothing which could stop it.

But the Greek system was not as responsive as the Roman one. The fact that a Roman officer could break away from his main force in an independent unit and so swing around to attack the Macedonian main force from behind illustrates this point perfectly.

If the Romans reported to have lost 700 men, then 13’000 Macedonians were either killed or taken captive.

Rome’s victory was absolute, Macedon’s threat to the Greek states was no more and Philip V had to sue for peace, accepting Rome’s terms.

Had Rome not won any land, it had now essentially established itself as the protector of Greece.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.