Last Updated on November 21, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

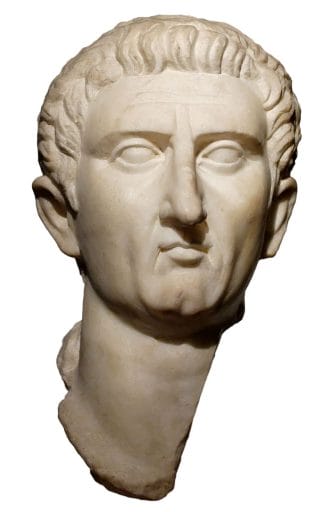

Life: AD 30 – 98

- Name: Marcus Cocceius Nerva

- Born on 8 November AD 30 at Narnia.

- Consul AD 71, 90, 97, 98.

- Became emperor on 18 September AD 96.

- Wives unknown. Adopted Trajan as successor October AD 97.

- Died in Rome, on 28 January AD 98.

Marcus Cocceius Nerva was born on 8 November in Narnia, 50 miles north of Rome. He was born into the household of a wealthy lawyer whose family was well accustomed to holding high office. His great-grandfather had even been consul in 36 BC and his grandfather had been a member of emperor Tiberius’ imperial entourage. Nerva’s mother was even the great-granddaughter of Tiberius. His grandfather was in the imperial entourage at the time of his birth. His aunt on his mother’s side of the family was even the great-granddaughter of Tiberius.

When younger, he naturally followed in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps, gaining experience by holding a series of official positions. Nerva showed great political talent in his ability to hold onto high office as emperors came and went.

On His Way to Become the Emperor

In AD 65 Nero awarded Nerva special honors for his help in suppressing the conspiracy of Piso. Despite this Vespasian chose him to be his colleague as consul in AD 71, and in AD 90 yet again he was chosen as a consular colleague to an emperor, this time Domitian. Such continuous success in high office marks Nerva as a man who enjoyed respect from all sides of Roman society. However, there was a rumor that Nerva had sexually abused Domitian in his youth (as reported by the historian Suetonius).

Nerva, much like Claudius earlier, was by all accounts most likely a reluctant emperor. He appears to especially seek out this office for himself. The historian Cassius Dio tells how Nerva, apparently in danger of being accused of treason by a paranoid Domitian, was approached by the conspirators planning the emperor’s murder. It seemed he accepted the role of successor more to save his own life than out of ambition.

New Emperor

Whether the version of events is true or not, Nerva’s accession to the throne was greeted with relief by many leading figures, tired of Domitian’s tyranny.

Already in his sixties when he came to power, he was an old man by Roman standards. He is said to have been frail and often ill, with a tendency to vomit up his food and a habit of overindulging with wine. He was a kind and amiable ruler. And he was one of the very few, perhaps even the only emperor, who could make this famous claim: ‘I have done nothing as emperor that would prevent my laying down the imperial office and returning to private life in safety.’

The senate acclaimed emperor by the senate on 18 September AD 96, on the very same day of Domitian’s death. Domitian had been despised by the senate. Once the hated emperor was gone, popular anger vented itself on Domitian’s statues and arches which were all demolished. Domitian’s extensive network of informers was abandoned, and some of the spies were even executed. Furthermore, an amnesty was granted to those who had been banished from Rome by Domitian and their properties were restored to them. The tyrant gone there was a general sense of euphoria.

.jpg)

Problems

In fact, Nerva’s popularity among the senators earned him the title pater patriae (father of the country) at the beginning of his reign. For such honors, other emperors had to wait for years. The feeling of rediscovered liberty among Romans brought with it new problems. For an elderly Nerva had difficulty restoring order. If under Domitian, nobody had been allowed to do anything, then now under Nerva, everyone did whatever they liked.

Nerva’s policies were largely meant to increase his popularity, but could also be seen as good government. Storehouses were built for grain, and aqueducts received much-needed repairs and maintenance. He famously took a public oath not to execute any senators, remaining true to his word, even when Senator Calpurnius Crassus was proven guilty of conspiracy against him.

More exemptions from inheritance tax were granted and land was distributed to the poor. Nerva used much of his own wealth to help pay for the cost of such measures. Nerva may have been popular with the people and the senate, but the army still held dear the memory of Domitian, who had given them their first pay rise since emperor Augustus.

On the Verge of a Civil War

Alas, relations with the military reached a crisis point in the summer of AD 97. Nerva had made the mistake of replacing the praetorian prefects Secundus and Norbanus, who it was thought could not be kept in their positions after their part in the assassination of Domitian.

Instead, Casperius Aelianus, a former supporter of Domitian (!), had been put in charge of the guards. And so the praetorian guard under its new leader mutinied against the emperor. Nerva was imprisoned in the palace and it was demanded that Petronius and Parthenius (as well as the previous prefect Secundus) be handed over to the praetorians for execution, due to their role in the murder of Domitian. Nerva bravely resisted these demands, even baring his own throat to the soldiers, that they should kill him rather than to kill Petronius and Parthenius.

But such gestures were in vain, as the praetorians seized their helpless victims and dragged them away. Petronius met the more merciful death, being killed with a single blow of the sword. The helpless Parthenius meanwhile had his genitals cut from his body and pushed into his mouth before finally having his throat cut.

And as though all this cruelty was not enough Nerva was actually forced to thank the praetorians in public for these executions. Though Nerva was unharmed, his authority was left in tatters by this incident. An emperor without the support of the army could not hope for a long reign.

Though Nerva was a, if anything, a skilled politician. And he now made his most inspired move of all. As a childless emperor, his death would leave the throne vacant, unless Nerva should choose to adopt an heir. And in finding a popular heir, Nerva knew he could secure his own position.

Heir and Death

And so Nerva selected as his heir, the governor of Upper Germany, Marcus Ulpius Trajanus. Trajan enjoyed tremendous respect and support among the army as well as the senate and appeared to embody all that Rome sought in an emperor. With Trajan as heino one dared challenge Nerva’s position again. The official adoption took place at the end of October AD 97 with a public ceremony at the Capitol.

Nerva’s died after a brief reign of only 16 months, on 28 January AD 98. In a fit of anger, he suddenly began sweating profusely. Soon after this, he developed a fever, and he died shortly afterward. He was by the senate. As a further sign of respect, his ashes were placed in the Mausoleum of Augustus, next to those of the Julio-Claudian emperors. Even the gods, so it seemed, were saddened at his death, as on the day of his burial there was an eclipse of the sun.

People also ask:

Was Nerva a good or bad emperor?

Historians believe Nerva was a wise and fair emperor. It was during Nerva’s reign that the custom of selecting the best heir to be emperor began. He is credited for the peaceful transition of power to Trajan as his successor before his death.

How did Nerva prevent civil war?

He joined the adoption immediately after the tribunicia potestas designation as consul for AD 98, both of which were to be held together so that Trajan would actually become a co-emperor. In this way, he managed to protect Rome from a possible civil war by entrusting the throne to one person.

Who was the last good emperor of Rome?

The last of the Five Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius is a reminder that despite the saying that “absolute power corrupts absolutely,” that is not always the case. At the time of his death, he was one of the most powerful people on earth.

Why did Nerva lose power?

Although Nerva’s brief reign was marred by financial difficulties and his inability to assert his authority over the Roman army (who were still loyal to Domitian), his greatest success was his ability to ensure a peaceful transition of power after his death, thus founding the Nerva-Antonine Dynasty.

How did Nerva change Rome?

Emperor Nerva’s role in Roman history was a stabilizing one. He prevented the outbreak of a civil war after the death of Domitian. He was also an ally to the poor of Rome and was well regarded as a fair ruler. He contributed to the construction of aqueducts, though they were not completed until after his death.

What is the timeline of Nerva?

- 8 Nov 35 CE. Birth.

- 13 Sep 81 CE. Death of Roman Emperor Titus.

- 18 Sep 96 CE – 27 Jan 98 CE. Reign of Roman Emperor Nerva.

- 18 Sep 96 CE. Death of Roman Emperor Domitian.

- Oct 97 CE. Adoption of Trajan.

- 28 Jan 98 CE. Death.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.