Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD c. 190 – 251

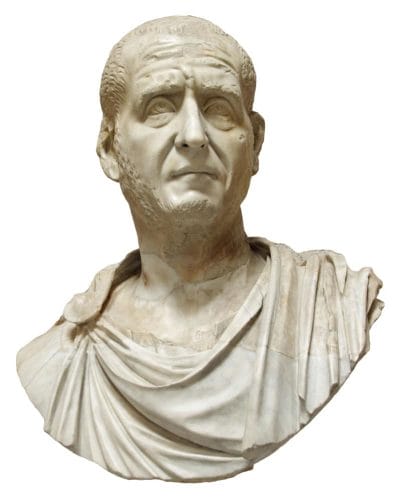

- Name: Gaius Messius Quintus Decius

- Born AD ca. 190.

- Became emperor in Sept/Oct AD 249.

- Wife: Herennia Cupressenia Etruscilla (two sons; Quintus Herrenius Decius; Gaius Valens Hostilianus).

- Died at Abrittus in Moesia, June AD 251.

- Deified AD 251.

Gaius Messius Quintus Decius was born around the year AD 190 in a village called Budalia near Sirmium. He wasn’t however from simple beginnings, as his family had influential connections and also had possession of considerable tracts of land.

Also he was married to Herennia Cupressenia Etruscilla, a daughter of old Etruscan aristocracy.

He rose to become senator and even consul, no doubt aided largely by the family’s wealth. Inscriptions can be found in Spain referring to a Quintus Decius Valerinus and in Lower Moesia to a Gaius Messius Quintus Decius Valerianus, which do suggest that he at some stage most likely held governorships to those provinces. Although the differing names are cause for some confusion.

When emperor Philippus Arabs, fearing the collapse of the empire in face of rebellions and barbarian invasions, spoke to the senate in AD 248 offering his resignation, it was Decius, then city prefect of Rome, who dissuaded him to stay in power, forecasting that the usurpers would surely soon die at the hands of their own troops.

Shortly afterwards Decius accepted a special command along the Danube to drive out the invading Goths to and restore order among the mutinous troops. He did as he was bid in very short time, proving himself a very able leader.

Too able it appears, as the troops hailed him emperor apparently against his will. He sought to reassure Philippus, but the emperor instead gathered troops and moved north to see the pretender to his throne killed.

Decius was forced to act and took his Danubian troops, traditionally the best of the empire, on a march southwards. The two forces met in September or October AD 249 at Verona, where Philippus’ larger army was defeated, leaving Decius sole emperor of the Roman world.

The senate confirmed him as emperor on his arrival at Rome. On this occasion Decius adopted the name Trajanus (hence he is often referred to as ‘Trajanus Decius’) as an addition to his name as a sign of his intention to rule in similar fashion to the great Trajan.

The first year of Decius’ reign was taken up by re-organizing the empire, particular effort being made toward a restoration of the empire’s official cults and rites. This reaffirmation of traditional Roman beliefs however was also responsible for what Decius’ rule is most remembered for; – persecution of the Christians. The religious edicts of Decius did not actually discriminate against Christians in particular. Far more it was demanded that every citizen of the empire should make sacrifice to the state gods. Anyone who refused faced execution. However in practice these laws impacted most heavily on the Christian community. Among the many execution of Christians to have taken place under Decius, Pope Fabianus was no doubt the most famous.

In AD 250 news reached the capital of a large-scale crossing of the Danube by the Goths under the leadership of their able king Kniva. At the same time the Carpi were once again attacking Dacia. The Goths divided their forces. One column moved into Thrace and besieged Philippopolis, while king Kniva moved eastwards. The governor of Moesia, Trebonianus Gallus, though managed to force Kniva to pull back. Though Kniva was not yet done, as he went on to besiege Nicopolis ad Istrum.

Decius gathered his troops, handed government to a distinguished senator, Publius Licinius Valerianus, and moved to drive the invaders out himself (AD 250). Before leaving he also proclaimed his Herennius Etruscus Caesar (junior emperor), assuring an heir was in place, should he fall whilst campaigning.

The young Caesar was sent ahead to Moesia with an advance column whilst Decius followed with the main army. At first all went well. King Kniva was driven from Nicopolis, suffering heavy losses, and the Carpi were forced out of Dacia. But while trying to drive Kniva out of Roman territory altogether, Decius suffered a serious setback at Beroe Augusta Trajana.

Titus Julius Priscus, governor of Thrace, realized the siege of his provincial capital Philippopolis could hardly be lifted after this disaster. As an act of despair he tried to save the city by declaring himself emperor and joining with the Goths. The desperate gamble failed, with the barbarians sacking the city and murdering their apparent ally.

Leaving Thrace to the devastation of the Goths, the emperor withdrew with his defeated army to join with the forces of Trebonianus Gallus.

In AD 251 following year Decius engaged the Goths again, as they were retreating back into their territory and achieved another victory of the barbarians.

In celebration of this event his son Herennius was now elevated to Augustus, whilst his younger brother Hostilianus, who was back in Rome, was promoted to the rank of Caesar (junior emperor).

Though soon the emperor was to learn of a new usurper. This time, in early AD 251, it was Julius Valens Licinianus (in Gaul, or at Rome itself), who enjoyed considerable popularity and acted apparently with the support of the senate. But Publius Licinius Valerianus, the man Decius had especially appointed to oversee matters of government back home in the capital put down the rebellion. By the end of March Valens was dead.

But in June/July AD 251 Decius too met his end. When king Kniva pulled out of the Balkans with his main force to return back over the Danube he met with Decius’ army at Abrittus. Decius was no match for the tactics of of Kniva. His army was trapped and annihilated. Both Decius and his son Herennius Etruscus were killed in battle.

The senate deified both Decius and his son Herennius shortly after their deaths.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.