Last Updated on October 23, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

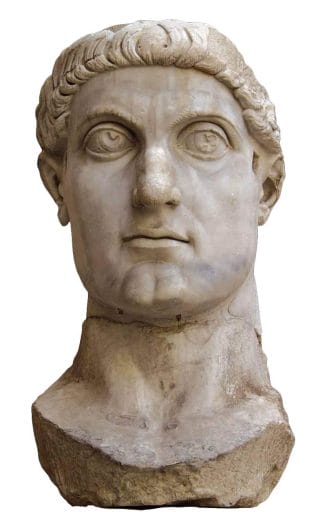

Life: AD c. 285 – 337

- Name: Flavius Valerius Constantinus

- Born on 27 February AD 285 (or AD 272/273) at Naissus.

- Consul AD 307, 312, 313, 315, 319, 320, 326, 329.

- Became emperor in AD 307.

- Wife: (1) Minervina (one son; Gaius Flavius Julius Crispus), (2) Fausta (three sons; Flavius Claudius Constantinus, Flavius Julius Constantius, Flavius Julius Constans; two daughters; Constantia, Helena)

- Died at Ankyrona near Nicomedia, 22 May AD 337.

- Deified AD 337.

Constantine the Great was born in Naissus, Upper Moesia, on 27 February in roughly AD 285. Another account places the year at about AD 272 or 273.

Rise to Power

He was the son of Helena, an innkeeper’s daughter, and Constantius Chlorus. It is unclear if the two were married and so Constantine may well have been an illegitimate child.

When in Constantius Chlorus in AD 293 was elevated to the rank of Caesar, Constantine became a member of the court of Diocletian. Constantine proved an officer of much promise when serving under Diocletian’s Caesar Galerius against the Persians.

He was still with Galerius when Diocletian and Maximian abdicated in AD 305, finding himself in the precarious situation of a virtual hostage to Galerius. In AD 306 though Galerius, now sure of his position as dominant Augustus (despite Constantius being senior by rank) let Constantine return to his father to accompany him on a campaign to Britain. Constantine however was so suspicious of this sudden change of heart by Galerius, that he took extensive precautions on his journey to Britain.

Augustus

When Constantius Chlorus in AD 306 died of illness at Ebucarum (York), the troops hailed Constantine the Great as the new Augustus. Galerius refused to accept this proclamation but, faced with strong support for Constantius’ son, he saw himself forced to grant Constantine the rank of Caesar.

When Constantine married Fausta, her father Maximian, now returned to power in Rome, acknowledged him as Augustus. Hence, when Maximian and Maxentius later became enemies, Maximian was granted shelter at Constantine’s court. At the Conference of Carnuntum in AD 308, where all the Caesars and Augusti met, it was demanded that Constantine give up his title of Augustus and return to being a Caesar. However, he refused.

Not long after the famous conference, Constantine was successfully campaigning against marauding Germans when news reached him that Maximian, still residing at his court, had turned against him. Had Maximian been forced to abdicate at the Conference of Carnuntum, then he now was making yet another bid for power, seeking to usurp Constantine’s throne.

Civil War

Denying Maximian any time to organize his defense, Constantine immediately marched his legions into Gaul. All Maximian could do was flee to Massilia. Constantine did not relent and laid siege to the city. The garrison of Massilia surrendered and Maximian either committed suicide or was executed (AD 310). With Galerius dead in AD 311 the main authority amongst the emperors had been removed, leaving them to struggle for dominance.

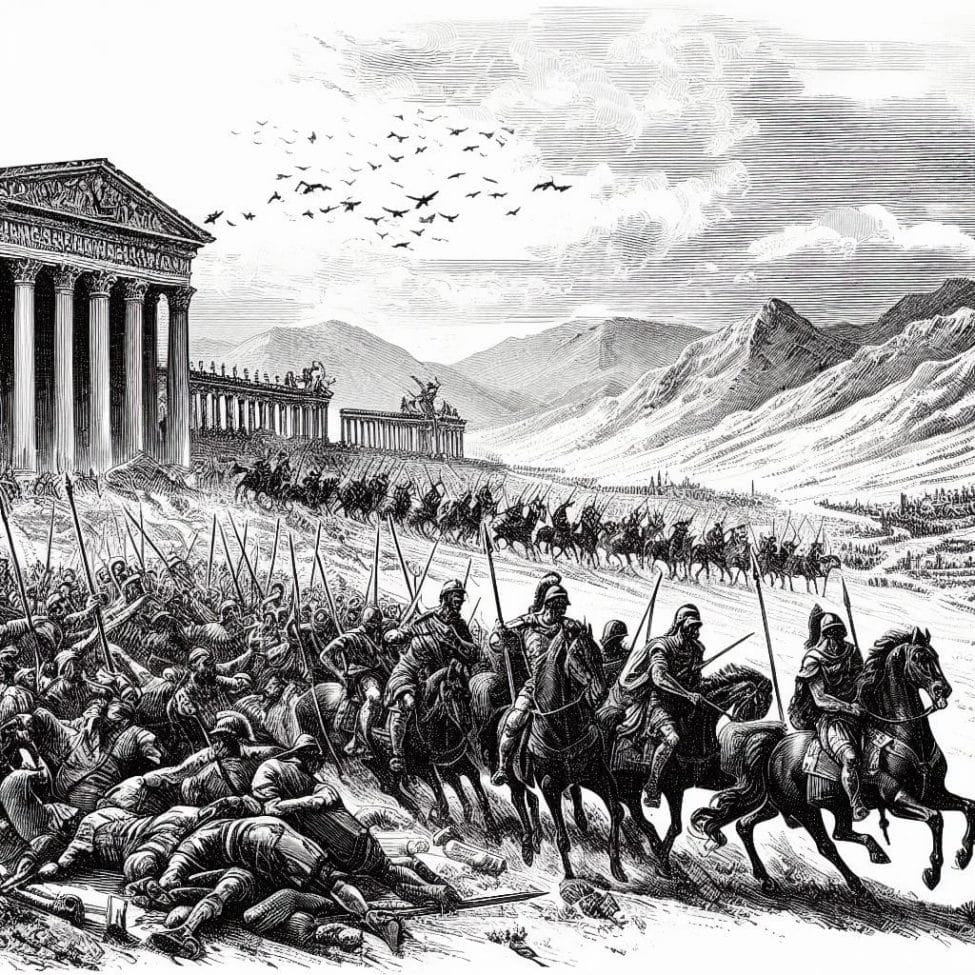

In the east Licinius and Maximinus Daia fought for supremacy and in the west Constantine began a war with Maxentius. In AD 312 Constantine invaded Italy. Maxentius is believed to have had up to four times as many troops, though they were inexperienced and undisciplined. Brushing aside the opposition in battles at Augusta Taurinorum (Turin) and Verona, Constantine marched on Rome.

The Milivian Bridge

Constantine later claimed to have had a vision on the way to Rome, during the night before battle. In this dream he supposedly saw the ‘Chi-Ro’, the symbol of Christ, shining above the sun. Seeing this as a divine sign, it is said that Constantine had his soldiers paint the symbol on their shields. Following this Constantine went on to defeat the numerically stronger army of Maxentius at the Battle at the Milvian Bridge (Oct AD 312).

Constantine’s opponent Maxentius, together with thousands of his soldiers, drowned as the bridge of boats his force was retreating over collapsed. Constantine saw this victory as directly related to the vision he had had the night before.

Henceforth Constantine saw himself as an ’emperor of the Christian people’. If this made him a Christian is the subject of some debate. But Constantine, who only had himself baptized on his deathbed, is generally understood as the first Christian emperor of the Roman world.

With his victory over Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge, Constantine the Great became the dominant figure in the empire. The senate warmly welcomed him to Rome and the two remaining emperors, Licinius and Maximinus II Daia could do little else but agree to his demand that he henceforth should be the senior Augustus. It was in this senior position that Constantine ordered Maximinus II Daia to cease his repression of the Christians.

And Then, There Were Two

Despite this turn toward Christianity, Constantine the Great remained for some years still very tolerant of the old pagan religions. Particularly the worship of the sun god was still closely related with him for some time to come. A fact that can be seen on the carvings of his triumphal Arch in Rome and on coins minted during his reign. Then in AD 313, Licinius defeated Maximinus II Daia. This left only two emperors.

At first, both tried to live peacefully aside from each other, Constantine in the west, and Licinius in the east. In AD 313 they met at Mediolanum (Milan), where Licinius even married Constantine’s sister Constantia and restated that Constantine was the senior Augustus. Yet it was made clear that Licinius would make his own laws in the east, without the need to consult Constantine. Further, it was agreed that Licinius would return property to the Christian church which had been confiscated in the eastern provinces.

Christianity

As time went on Constantine should become ever more involved with the Christian church. He appeared at first to have very little grasp of the basic beliefs governing the Christian faith. But gradually he must have become more acquainted with them. So much so that he sought to resolve theological disputes among the church itself.

In this role, he summoned the bishops of the western provinces to Arelate (Arles) in AD 314, after the so-called Donatist schism had split the church in Africa. If this willingness to resolve matters through peaceful debate showed one side of Constantine, then his brutal enforcement of the decisions reached at such meetings showed the other. Following the decision of the council of bishops at Arelate, donatist churches were confiscated and the followers of this branch of Christianity were brutally repressed. Evidently, Constantine the Great was also capable of persecuting Christians if they were deemed to be the ‘wrong type of Christians’.

The War with Licinius

Problems with Licinius arose when Constantine the Great appointed his brother-in-law Bassianus as Caesar for Italy and the Danubian provinces. If the principle of the tetrarchy, established by Diocletian, still in theory defined government, then Constantine as senior Augustus had the right to do this. And yet, Diocletian’s principles would have demanded that he appointed an independent man on merit. But Licinius saw in Bassianus little else than a puppet of Constantine the Great.

If the Italian territories were Constantine’s, then the important Danubian military provinces were under the control of Licinius. If Bassianus was indeed Constantine’s puppet it would have meant a serious gain of power by Constantine. And so, to prevent his opponent from further increasing his power, Licinius managed to persuade Bassianus to revolt against Constantine in AD 314 or AD 315.

The rebellion was easily put down, but the involvement of Licinius, too, was discovered. And this discovery made war inevitable. But considering the situation responsibility for the war must lie with Constantine. It appears that he was simply unwilling to share power and hence sought to find means by which to bring about a fight.

For a while, neither side acted, instead both camps preferred to prepare for the contest ahead. Then in AD 316, Constantine attacked with his forces. In July or August at Cibalae in Pannonia he defeated Licinius’s larger army, forcing his opponent to retreat.

Temporary Peace

The next step was taken by Licinius, when he announced Aurelius Valerius Valens, to be the new emperor of the west. It was an attempt to undermine Constantine, but it clearly failed to work. Soon after, another battle followed, at Campus Ardiensis in Thrace. This time, however, neither side gained victory, as the battle proved indecisive.

Once more the two sides reached a treaty (1 March AD 317). Licinius surrendered all Danubian and Balkan provinces, with the exception of Thrace, to Constantine. In effect, this was little else but confirmation of the actual balance of power, as Constantine the Great had indeed conquered these territories and controlled them. Despite his weaker position, Licinius still retained complete sovereignty over his remaining eastern dominions. Also as part of the treaty, Licinius’ alternative western Augustus was put to death.

The final part of this agreement reached at Serdica was the creation of three new Caesars. Crispus and Constantine II were both sons of Constantine and Licinius the Younger was the infant son of the eastern emperor and his wife Constantia.

For a short while the empire should enjoy peace. But soon the situation began to deteriorate again. If Constantine the Great acted more and more in favor of the Christians, then Licinius began to disagree. From AD 320 onwards Licinius began to suppress the Christian church in his eastern provinces and also began ejecting any Christians from government posts.

Another problem arose regarding the consulships. These were by now widely understood as positions in which emperors would groom their sons as future rulers. Their treaty at Serdica had hence proposed that appointments should be made by mutual agreement. Licinius though believed Constantine favoured his own sons when granting these positions.

The Final Conflict

And so, in clear defiance of their agreements, Licinius appointed himself and his two sons consuls for the eastern provinces for the year AD 322. With this declaration, it was clear that hostilities between the two sides would soon begin afresh. Both sides began to prepare for the struggle ahead.

In AD 323 Constantine the Great created yet another Caesar by elevating his third son Constantius II to this rank. If the eastern and western halves of the empire were hostile towards one another, then in AD 323 a reason was soon found to start a new civil war. Constantine, while campaigning against Gothic invaders, strayed into Licinius’ Thracian territory. It is possible he did so purposely in order to provoke a war. Be that as it may, Licinius took this as the reason to declare war in the spring of AD 324.

Hadrianopolis

But it was once again Constantine the Great who moved to attack first in AD 324 with 120,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry against Licinius’ 150,000 infantry and 15,000 cavalry based at Hadrianopolis. On 3 July AD 324, he severely defeated Licinius’ forces at Hadrianopolis, and shortly after his fleet won victories at sea.

Licinius fled across the Bosporus to Asia Minor (Turkey), but Constantine having brought with him a fleet of two thousand transport vessels ferried his army across the water and forced the decisive battle of Chrysopolis where he utterly defeated Licinius (18 September AD 324). Licinius was imprisoned and later executed. Alas, Constantine the Great was the sole emperor of the entire Roman world.

Reforms

Soon after his victory in AD 324, he outlawed pagan sacrifices, now feeling far more at liberty to enforce his new religious policy. The treasures of pagan temples were confiscated and used to pay for the construction of new Christian churches. Gladiatorial contests were outruled and harsh new laws were issued prohibiting sexual immorality. Jews in particular were forbidden from owning Christian slaves.

Constantine the Great continued the reorganization of the army, begun by Diocletian, reaffirming the difference between frontier garrisons and mobile forces. The mobile forces consisted largely of heavy cavalry which could quickly move to trouble spots. The presence of Germans continued to increase during his reign. The praetorian guard who’d held such influence over the empire for so long, was finally disbanded. Their place was taken by the mounted guard, largely consisting of Germans, which had been introduced under Diocletian.

Constantine the Great as a Cruel Emperor

As a lawmaker, Constantine was terribly severe. Edicts were passed by which the sons were forced to take up the professions of their fathers. Not only was this terribly harsh on such sons who sought a different career. But by making the recruitment of veterans’ sons compulsory, and enforcing it ruthlessly with harsh penalties, widespread fear and hatred were caused.

Also, his taxation reforms created extreme hardship. City dwellers were obliged to pay a tax in gold or silver, the chrysargyron. This tax was levied every four years, beating and torture being the consequences for those too poor to pay. Parents are said to have sold their daughters into prostitution in order to pay the chrysargyron.

Under Constantine the Great, any girl who ran away with her lover was burned alive. Any chaperone who should assist in such a matter had molten lead poured into her mouth. Rapists were burned at the stake. But also their women victims were punished, if they had been raped away from home, as they, according to Constantine, should have no business outside the safety of their own homes.

The Eastern Capital

Constantine the Great is perhaps most famous for the great city which came to bear his name – Constantinople.

He came to the conclusion that Rome had ceased to be a practical capital for the empire from which the emperor could exact effective control over its frontiers. For a while he set up courts in different places; Treviri (Trier), Arelate (Arles), Mediolanum (Milan), Ticinum, Sirmium, and Serdica (Sofia). Then he decided on the ancient Greek city of Byzantium. On 8 November AD 324, Constantine created his new capital there, renaming it Constantinopolis (City of Constantine).

He was careful to maintain Rome’s ancient privileges, and the new senate founded in Constantinople was of a lower rank, but he clearly intended it to be the new center of the Roman world. Measures to encourage its growth were introduced, most importantly the diversion of the Egyptian grain supplies, which had traditionally gone to Rome, to Constantinople. A Roman-style corn dole was introduced, granting every citizen a guaranteed ration of grain.

Harsh Laws

In AD 325 Constantine the Great once again held a religious council, summoning the bishops of the east and west to Nicaea. At this council, the branch of the Christian faith known as Arianism was condemned as a heresy, and the only admissible Christian creed of the day (the Nicene Creed) was precisely defined.

Constantine’s reign was that of a hard, utterly determined, and ruthless man. Nowhere did this show more than when in AD 326, on suspicion of adultery or treason, he had his own eldest son Crispus executed.

One account of the events tells of Constantine’s wife Fausta falling in love with Crispus, who was her stepson, and made an accusation of him committing adultery only once she had been rejected by him, or because she simply wanted Crispus out of the way, in order to let her sons acceed to the throne unhindered. Then again, Constantine the Great had only a month ago passed a strict law against adultery and might have felt obliged to act. And so Crispus was executed at Pola in Istria.

Though after this execution Constantine’s mother Helena convinced the emperor of Crispus’ innocence and that Fausta’s accusation had been false. Escaping the vengeance of her husband, Fausta killed herself at Treviri.

Later Years

A brilliant general, Constantine the Great was a man of boundless energy and determination, yet vain, receptive to flattery, and suffering from a choleric temper.

Had Constantine defeated all contenders to the Roman throne, the need to defend the borders against the northern barbarians still remained.

In the autumn of AD 328, accompanied by Constantine II, he campaigned against the Alemanni on the Rhine. This was followed in late AD 332 by a large campaign against the Goths along the Danube until in AD 336 he had re-conquered much of Dacia, once annexed by Trajan and abandoned by Aurelian.

In AD 333 Constantine’s fourth son Constans was raised to the rank of Caesar, with in the clear intent to groom him, alongside his brothers, to jointly inherit the empire. Also, Constantine’s nephews Flavius Dalmatius (who may have been raised to Caesar by Constantine in AD 335 !) and Hannibalianus were raised as future emperors. Evidently, they also were intended to be granted their shares of power at Constantine’s death.

How, after his own experience of the tetrarchy, Constantine saw it possible that all five of these heirs should rule peaceably alongside each other, is hard to understand.

Plans of Expansion

In old age, Constantine the Great planned a last great campaign, one which was intended to conquer Persia. He even intended to have himself baptized as a Christian on the way to the frontier in the waters of the river Jordan, just as Jesus had been baptized there by John the Baptist.

As the ruler of these soon-to-be conquered territories, Constantine the Great even placed his nephew Hannibalianus on the throne of Armenia, with the title of King of Kings, which had been the traditional title borne by the kings of Persia. But this scheme was not to come to anything, for in the spring of AD 337, Constantine fell ill. Realizing that he was about to die, he asked to be baptized. This was performed on his deathbed by Eusebius, bishop of Nicomedia.

Death

Constantine the Great died on 22 May AD 337 at the imperial villa at Ankyrona. His body was carried to the Church of the Holy Apostles, his mausoleum. Had his own wish to be buried in Constantinople caused outrage in Rome, the Roman senate still decided on his deification. A strange decision as it elevated him, the first Christian emperor, to the status of an old pagan deity. Constantine the Great is venerated as “Saint Constantine” in Eastern Christian churches.

People Also Ask:

What is Constantine the Great famous for?

Constantine the Great made Christianity the main religion of Rome and created Constantinople, which became the most powerful city in the world.

What are 3 things Constantine the Great did?

Some of his important accomplishments include his support of Christianity, the construction of the city of Constantinople, and the continuance of the reforms of Diocletian.

Did Constantine the Great convert to Christianity?

Constantine the Great converted to Christianity in 312 AD

Was Constantine the Great a good emperor?

He is known as Constantine the Great for very good reasons. After nearly 80 years, and three generations of political fragmentation, Constantine united the whole of the Roman Empire under one ruler. By 324 he had extended his power and was sole emperor, restoring stability and security to the Roman world.

Who founded Constantinople?

Constantine the Great.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.