Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD c. 250 – 306

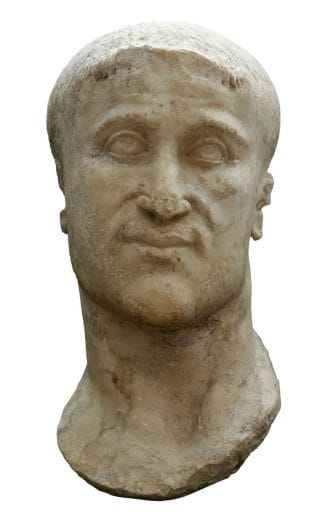

- Name: Flavius Julius Constantius

- Born 31 March AD ca. 250 in Illyricum.

- Became emperor in 1 May AD 305.

- Wife: (1) Helena (one son; Constantine), (2) Theodora ( two sons; Flavius Dalmatius, Flavius Julius Constantius; third child unknown).

- Died at Ebucarum (York), 25 July AD 306.

Flavius Julius Constantius, like the other emperors of the day, was of poor Danubian family and had worked his way up through the ranks of the army.

The famous addition of ‘Chlorus’ to his name, came from his pale complexion, for it’s meaning is ‘the pale’.

Somewhen in the AD 280’s Constantius had an affair with an innkeeper’s daughter called Helena. It is unclear if the two actually married or not, but what is not is that she bore him a son, – Constantine.

Later though this relationship broke up and Constantius in AD 289 married instead Theodora, the stepdaughter of emperor Maximian, whose praetorian prefect he became.

Then, as Diocletian created the tetrarchy in AD 293, Constantius was chosen as Caesar (junior emperor) by Maximian and adopted as his son. It was due to this imperial adoption that Constantius’ family name now changed from Julius to Valerius.

Of the two Caesars, Constantius was the senior (just as Diocletian was the senior of the two Augusti).

The northwestern territories over which he was granted rule, were perhaps the most difficult area one could have been given at the time. For Britain and the Channel coast of Gaul were in the hands of Carausius’ break-away empire and his allies, the Franks.

During the summer of AD 293 Constantius drove out the Franks and then, after a hard-fought siege, conquered the city of Gesoriacum (Boulogne), which crippled the enemy and eventually brought Carausius’ downfall.

But the break-away realm did not immediately collapse. It was Allectus, Carausius’ murderer, who now continued its rule, although since the fall of Gesoriacum it was hopelessly enfeebled.

But Constantius was not about to rashly charge into Britain and risk losing any advantage he had gained. He took no less than two years to consolidate his position in Gaul, dealing with any remaining allies of the enemy, and to prepare his invasion force.

Alas, in AD 296 his invasion fleet left Gesoriacum (Boulogne). The force was divided into two squadrons, one led by Constantius himself, the other by his praetorian prefect Asclepiodotus.

The thick fog across the Channel acted both as a hindrance and an ally.

It caused all kind of confusion in Constantius’ part of the fleet, causing it to get lost and forcing it back to Gaul. But it also helped the squadron of Asclepiodotus to slip past the enemy fleet and land his troops.

And so it was Asclepiodotus’ army which met up with that of Allectus and defeated it in battle. Allectus himself lost his life in this contest. If the bulk of Constantius’ squadron had been turned back by the fog, then a few of his ships appeared to make it across on their own. Their forces united and made their way to Londinium (London) where they defeated what remained of the forces of Allectus. – This was the excuse Constantius needed to claim the glory for reconquering Britain.

In AD 298 Constantius defeated an invasion by the Alemanni who crossed the Rhine and besieged the town of Andematunum.

For several years thereafter Constantius enjoyed a peaceful reign.

Then, following the abdication of Diocletian and Maximian in AD 305, Constantius rose to become emperor of the west and senior Augustus. As part of his elevation Constantius had to adopt Severus II, who had been nominated by Maximian, as his son and western Caesar. Constantius’ of senior rank as Augustus though was purely theoretical, as Galerius in the east held more real power.

For Constantius realm only comprised the dioceses of Gaul, Viennensis, Britain and Spain, which were no match for Galerius’ control of the Danubian provinces and Asia Minor (Turkey).

Constantius was the most moderate of the emperors of the tetrarchy of Diocletian in his treatment of the Christians. In his territories Christians suffered the least form Diocletian’s persecutions. And following the rule of the brutish Maximian, Constantius’ rule was indeed a popular one.

But worrying for Constantius was that Galerius was host to his son Constantine. Galerius had virtually ‘inherited’ this guest from his predecessor Diocletian. And so, in practice Galerius had an effective hostage by which to assure Constantius’ compliance. This, apart from the imbalance of power between the two, assured that Constantius rather acted as the junior of the two Augusti. And his Caesar, Severus II, fell more under the authority of Galerius than that of Constantius.

But Constantius finally found a reason to demand the return of his son, when he explained a campaign agaisnt the Picts, who were invading the British provinces, required both his own and his son’s leadership. Galerius, evidently under pressure to comply or to admit that he was holding a royal hostage, conceded and let Constantine go.

Constantine caught up with his father at Gesoriacum (Boulogne) in early AD 306 and they crossed the Channel together.

Constantius went on to achieve a series of victories over the Picts, but then fell ill. He died soon after, 25 July AD 306, at Ebucarum (York).

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.