Last Updated on October 24, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD 161 – 192

- Name: Lucius Aurelius Commodus

- Born on 31 August AD 161 at Lanuvium.

- Consul AD 177,179,181,183,186,190,192.

- Became emperor on 17 March AD 180.

- Wife: Bruttia Crispina.

- Died in Rome on 31 December AD 192.

Commodus Early Life

Lucius Aurelius Commodus was born on 31 August AD 161 at Lanuvium, roughly 14 miles south-east of Rome.

Of the fourteen children of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina the Younger, Commodus was the tenth. He was born one of twins, though his twin brother died when he was only four years old. He was given the name Commodus in honor of Marcus Aurelius’ co-emperor, who had originally borne it.

Commodus was, in fact, the only son of the royal couple to survive childhood.

From an early age, Commodus was groomed to succeed his father to the throne. Already at the age of five, in the year AD 166, he was made Caesar (junior emperor). In AD 177, after the revolt of Cassius, Marcus Aurelius made him Augustus and, thereby, joint emperor. Commodus indeed led the troops in the wars on the Danube together with his father from AD 178 until the death of Marcus Aurelius in AD 180.

Had Commodus been emperor from AD 177, no one doubted that true power remained in the hands of his father. And so his reign is generally seen to have begun on the death of his father in AD 180.

Young Nero in the Making

By all accounts, he was a handsome man with curly blonde hair. However, he appeared to possess a weak character and was easily influenced by others. But he was also prone to cruelty and excessive behavior. To an extent, his behavior was still held in check when his father was still alive, although some believed they detected the signs of a new Nero in the young heir. Cassius’ earlier rebellion, when he mistakenly thought Marcus Aurelius had died, might well have been inspired by a fear of what was to come if Commodus came to the throne.

Commodus’ accession to power ended a spell of 80 years in Roman history, which had brought men to the throne by merit rather than by birth. The last man to take the throne merely by right of birth had been Domitian.

Commodus Ruling

If Commodus had not lived up to the gruelingly high standards of his father, the world would have most likely forgiven him. But rather than just failing to be a brilliant emperor, Commodus was, in fact, a terrible one. Cruelty, vanity, power, and fear formed into a terrifyingly dangerous mix of bloodlust, suspicion, and megalomania. Commodus should be remembered as a monster, a tyrant who renamed months in his own honor, and the one who slaughtered his way through the circuses in ludicrous displays of ‘manliness’.

Despite his initial promises to the army to continue Marcus Aurelius’ attempts to expand the empire into the territories conquered from the Quadi and Marcomanni, Commodus soon after surrendered all his father had achieved in his wars.

Indeed, his thoughts that annexing these new territories might have been beyond the capabilities of Rome could well have been correct. And, had emperor Hadrian not relinquished some of the gains of his predecessor Trajan? But Commodus was no Hadrian, and the army knew it. Commodus’ retreat from those so direly contested territories was understood as an utter betrayal of everything the beloved Marcus Aurelius had stood for.

Whatever the circumstances surrounding the Roman withdrawal, Commodus did make a treaty with the Marcomanni. The treaty proved very successful in pacifying the barbarians, forcing them to accept various conditions. However, such peace might also have been due to Marcus Aurelius’ late successes, having reduced the barbarians’ capacities for war.

Conspiracies and Executions

With peace re-established on the Danube, Commodus returned to Rome. It wasn’t long before he uncovered the first conspiracy against him. In AD 182, his sister Annia Lucilla, along with her cousin, the former consul Marcus Ummidius Quadratus, were involved in a plot to assassinate him.

Lucilla’s second husband Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus of Antioch, who had held the office of consul twice and was a possible rival to the throne, was whom the plotters sought to make emperor. And it was Pompeianus’ nephew Quintianus who burst from his place of hiding with a dagger, trying to stab Commodus. But the guards were faster than Quintianus. He was overpowered and disarmed without doing the emperor any harm. Quadratus and Quintianus were executed. Meanwhile, the emperor’s sister Lucilla was first banished to Caprae but was soon afterward put to death anyhow.

Not much later, the praetorian prefect Tarrutenius Paternus was also executed, either for being part of the plot to kill Commodus or for being a conspirator in the murder of the emperor’s influential court chamberlain from Bithynia called Saoterus (it might have been Saoterus’ advice which caused Commodus to withdraw from the territories his father had conquered beyond the Danube).

With the prefect Tarrutenius Paternus killed, the other remaining prefect, Tigidius Perennis, was left in sole charge of running the empire on the emperor’s behalf, for Commodus took little interest in the day-to-day running of government. Perhaps since the notorious prefect Sejanus during Tiberius’ reign, no praetorian commander had held so much power.

With Perennis in charge of running the empire, Commodus’ life became one long party. Entertaining a harem of, so it is said, 300 girls and women and 300 boys, some of which might have been kidnapped, he indulged in lengthy orgies and reveled in decadent luxuries.

But with his hands on all the levers of power, it was only a matter of time before Perennis himself was seen as too powerful by Commodus. Rumors that he was planning to rid himself of the emperor to rule on his own were further backed up by the fact that he made two of his sons governors of the important Danubian military province of Pannonia.

The End of Perennis

Though in AD 185, Perennis had been in power for three years, a delegation of 1500 disgruntled soldiers from the British legions arrived in Rome and warned Commodus of a plot by Perennis. Whether the praetorian prefect had really plotted against his emperor’s life remains unclear. But what is known is that Perennis had brutally crushed a mutiny in Britain, which will have won him no favors with the army based there. Whatever the true reason is, Perennis was killed by his own praetorians. So, too his wife, his sister, and his sons were all executed.

The man believed to have organized these executions on Commodus’ behalf was Marcus Aurelius Cleander, a freedman having once been brought to Rome as a Phrygian slave. Cleander now was placed in the vacant position of praetorian prefect and became not merely Commodus’ closest advisor but began to run the government on the emperor’s behalf as Perennis had done. As head of the emperor’s security, he was given the title pugione (‘the Dagger’) by Commodus. If there had been talk of corruption by Perennis, then Cleander achieved true notoriety by his greed. His might well have been the most corrupt government ever to have ruled the Roman empire.

Public offices were sold to the highest bidder, one year actually seeing no less than 25 consuls inaugurated. Cleander kept a lot of this money for himself but took care to share these revenues with his emperor. But, just as Cleander had helped bring down Perennis, then so did he fall. Papyrius Dionysius, the prefect of the grain supply to Rome (praefectus annonae), managed to engineer a food shortage in Rome and blamed it on Cleander. In AD 190, the garrison of Rome, accompanied by an angry mob, sought out Perennis and killed him. Commodus did nothing to save the head of his government.

Later Stages of Commodus’s reign

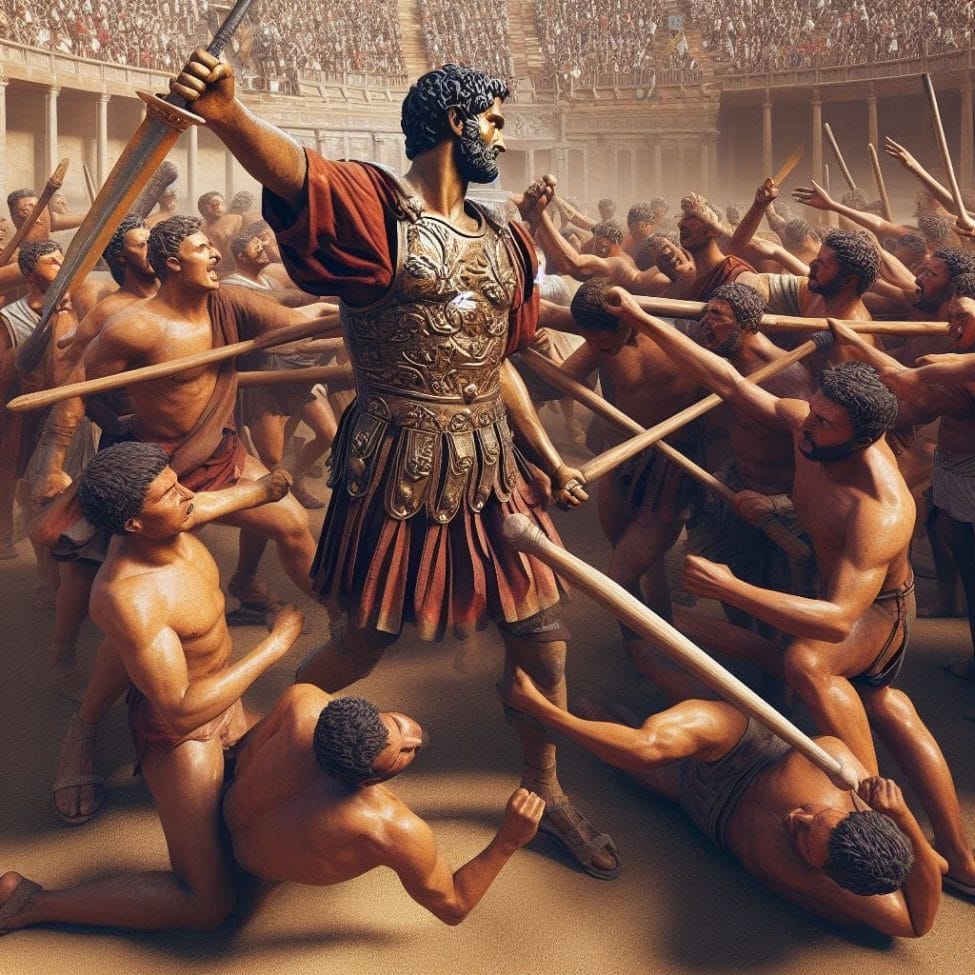

In the later stages of his reign, Commodus became ever more obsessed with performing as a gladiator. He even changed parts of his palace into an arena in order to fight beasts or gladiators. But Commodus was not satisfied with such private fights. He also appeared in public as a gladiator. For the Roman public, or at least the privileged classes, it was a harsh shock to see their emperor publicly debase himself to the level of a slave or a prostitute in the arena. For, in Roman attitudes, gladiators were indeed understood as one of the lowest possible levels of society.

But Commodus cared little about such attitudes. He liked to appear in the arena dressed up in a lion skin as the ancient hero Hercules, son of Jupiter. There is little doubt that by this time, Commodus was deranged. Senators had to be present at such performances as their emperor slaughtered helpless animals or hapless gladiators. One day, he is said to have killed one hundred bears. Given this number, it is hard to imagine that the animals were anything but helplessly tethered with no chance to fight back. The fighters who would meet Commodus in the arena stood equally little chance. For if the emperor was armed, all they would have were harmless wooden weapons.

Cruel as this, no doubt, Commodus also seemed ridiculous to many. Was gladiatorial combat also concerned with grace, as well as skill, the emperor apparently possessed little of it. Many spectators are said to have struggled not to laugh out loud at the sight of such ridiculous displays.

Inscribed on the base of one statue of his was that he had slain twelve thousand men. Whether this is true or not cannot be said. But it says much about the man to boast of such ‘achievements’. If Commodus sought to be Rome’s hero in the arena, if he even had the nobles ordered to call out prescripted compliments from the tiers, he also was jealous of any other gladiator’s fame. In one case, on hearing that a bestiarius (animal fighter) called Julius Alexander had on horseback killed a lion with a javelin, he had him executed.

“Roman Hercules”

As if this all wasn’t enough, Commodus decided that, in accordance with his divine talent, Romans should pay to see the prowess of the ‘Roman Hercules’ in the arena. And so he demanded to be paid one million sesterces from the gladiatorial fund for every appearance.

Only chariot racing was something Commodus would not do in public. This stigma he sought to avoid, even though the historian Dio Cassius mentions that, indeed, he did so on some nights when he might not be seen by the public. If he did so by day, Commodus made sure to do so out of sight. But, even on these occasions, he made sure to wear the livery of the popular ‘Green’ racing faction.

While the emperor was playing gladiator in Rome, the empire was facing hard times. The army was viewed with suspicion by a population that knew more and more spies and military secret police at work. Had the emperor nearly bankrupted the imperial treasury with his expensive lifestyle, then he simply replenished it by accusing senators of treason and having their property seized.

But things were to get even worse. In AD 191, a fire destroyed some of the center of Rome, and then Commodus had it rebuilt. But, wanting to claim the credit for the ‘rebuilding of Rome,’ he decided to rename the city altogether. Colonia Commodiana was to be its new name (City of Commodus).

So, too, the army should henceforth be the Commodian army, and even the ancient institution of the Roman senate was to bear his name in the future. Then, in November AD 192, plans emerged that to celebrate the ‘new’ city, Commodus was to take office as consul on 1 January AD 193. He even intended to march to the senate from a gladiatorial school within the city – dressed as a gladiator.

Assassination Plot

It appears to have been the praetorian prefect Quintus Aemilius Laetus who decided it was time to act against the madman on the throne.

Carefully, a plot was crafted against the emperor. The court chamberlain Eclectus and the emperor’s favorite concubine Marcia added their support to the undertaking. Quietly, people who supported the plot were placed into key positions. Septimius Severus and Clodius Albinus, African allies of Laetus, were given the governorships of Upper Pannonia and Britain. Pescennius Niger, another friend of Laetus, was put in charge of Syria. As the future emperor, the conspirators agreed on Publius Hevlius Pertinax, the city prefect of Rome.

The initial plan appeared to be that Marcia should poison him on the evening of 31 December AD 192. But Commodus merely became nauseous and vomited, ridding himself unwittingly of the poison. But, the plotters appeared to have a backup plan in place. An athlete called Narcissus, who was employed as Commodus’ wrestling partner, overpowered and strangled Commodus in his bed on the same night.

If Laetus had been the chief conspirator against Commodus, he would not saved Commodus’s body from being disgraced by carrying it away and giving it a secret burial outside Rome. The precaution proved worthwhile, for the senate now vented its anger on the tyrant, having his name removed from all records and destroying his statues.

Though in a strange twist of fate, the new emperor Pertinax should have Commodus’ body exhumed and laid to rest in the Mausoleum of Hadrian. Septimius Severus even had Commodus deified in AD 197.

People also ask:

Was Commodus a good or bad emperor?

How Bad Was He? In his 2021 book, Evil Roman Emperors: The Shocking History of Ancient Rome’s Most Wicked Rulers from Caligula to Nero and More, author Phillip Barlag awards Commodus the No. 1 spot, calling him a “self-indulgent, dim-witted oaf,” not to mention “sick, cruel, sadistic, deluded.”

What is Commodus most known for?

He became sole Emperor of the Roman Empire in 180 CE upon his father’s death. He is most famous for his love of the Gladiatorial Arena, even participating in it himself. Though Commodus now, in popular culture, is known as a cruel, erratic, and lecherous ruler he wasn’t a bad emperor in every respect.

Did Commodus really fight as a gladiator?

In all, Commodus participated in 735 contests as a gladiator, according to the Historia Augusta. With official matters left unattended, and an Emperor dishonoring his title, the Senate conspired to have the Emperor assassinated. They gave the task to the Emperor’s training partner, who carried out the gruesome deed.

How old was Commodus when he died?

After multiple escapes from assassination by his loved ones, Commodus was finally killed at age 31, and the memory of his reign was erased (not well enough).

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.