Last Updated on October 24, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

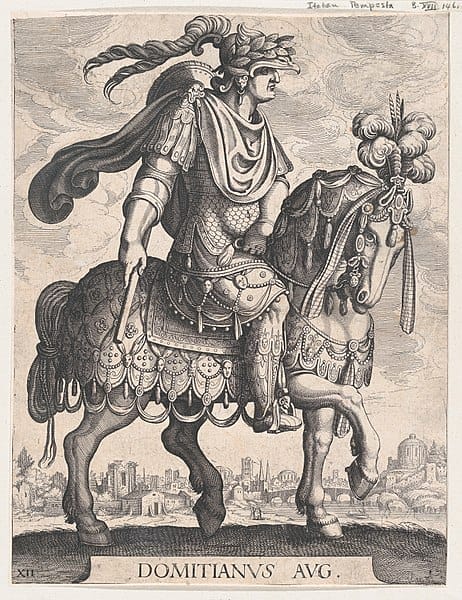

Life: 51 – 96 A.D.

- Name: Titus Flavius Domitianius Augustus

- Born on 24 October AD 51 in Rome

- Younger son of Vespasian and Flavia Domitilla.

- Became emperor on 14 September AD 81.

- Married Domitia Longina (no children).

- Murdered on 18 September AD 96.

Early Life of Domitian

Titus Flavius Domitianius was the younger son of Vespasian and Flavia Domitilla, born in AD 51 in Rome. He was the younger and the clearly less favored son of Vespasian, who cared much more for his heir, Titus.

During his father’s uprising against Vitellius in AD 69, Domitian was, in fact, in Rome, even though he remained unharmed. When the city prefect of Rome and elder brother of Vespasian, Titus Flavius Sabinus, attempted to seize power during the confusion about Vitellius’ alleged abdication, on 18 December AD 69, Domitian was with his uncle Sabinus. He hence went through the fighting on the Capitol, though, unlike Sabinus, he managed to escape.

For a short time after the arrival of his father’s troops, he enjoyed the privilege of acting as regent. Mucianus (the governor of Syria and ally of Vespasian who had led an army of 20,000 to Rome) acted as Domitian’s colleague in this regency and carefully kept Domitian in check.

For example, with there being rebels against the new regime in Germany and Gaul, Domitian was eager to seek glory in suppressing the revolt, trying to equal his brother Titus’ military exploits. But he was prevented from doing this by Mucianus. When Vespasian arrived in Rome to rule, it was made evidently clear to everyone that Titus was to be the imperial heir.

Domitian Position and ‘Potential’ heir

Titus had no son. Hence, if he failed to produce or adopt an heir, the throne would eventually fall to Domitian. Domitian, however, was never granted any position of authority nor allowed to win any military glory for himself. If Titus was meticulously groomed to be emperor, he received no such attention at all. Evidently, he was not deemed fit by his father to hold power. Domitian instead dedicated himself to poetry and the arts, though it is thought he harbored much resentment at his treatment.

When Titus eventually acceded to the throne in AD 79, nothing changed for Domitian. He was granted honors but nothing else. Relations between the two brothers were markedly cool, and it is largely believed that Titus shared his deceased father’s opinion that Domitian was not fit for office. In fact, Domitian later claimed that Titus had denied him what should have rightfully been his rightful place as imperial colleague. Titus died in AD 81, amongst rumors that Domitian had poisoned him. But more likely, he died from illness.

Becoming an Emperor

Domitian was not even to wait for his brother to die. While Titus lay dying, he hurried to the praetorian camp and had himself proclaimed emperor by the soldiers. The following day, 14 September AD 81, with Titus dead, he was confirmed emperor by the senate. His first act was, no doubt reluctantly, to enact Titus’ deification. He may have held a grudge, but his own interests were best served by further celebrating the Flavian house.

But now Domitian was determined to equal the military achievements of his predecessors. He wanted to be known as a conqueror. In AD 83, he completed the conquest of the Agri Decumates, the lands beyond the upper Rhine and the upper Danube, which his father Vespasian had begun. He moved against tribes like the Chatti and drove the empire’s frontier to the rivers Lahn and Main. After such victorious campaigns against the Germans, he would often wear the costume of a victorious general in public, at times also when he visited the senate.

Domitian Personality

Shortly after, he raised the pay of the army from 300 to 400 sesterces – a fact which should have naturally made him popular with the soldiers. However, by that time, a pay rise had perhaps become well necessary, as over time, inflation had reduced the soldiers’ income.

By all accounts, he appears to have been a thoroughly nasty person, rarely polite, insolent, arrogant, and cruel. He was a tall man with large eyes, though weak sight. And showing all the signs of someone drunk with power, he preferred to be addressed as ‘dominus et deus’ (‘master and god’).

In AD 83, Domitian displayed that terrifying adherence to the very letter of the law, which should make him so feared by the people of Rome. Three Vestal Virgins, convicted of immoral behavior, were put to death. It is true that these stringent rules and punishments had once been observed by Roman society. But times had changed, and the public now tended to see these punishments of the Vestals as mere acts of cruelty.

Meanwhile, the governor of Britain, Cnaeus Julius Agricola, was successfully campaigning against the Picts. He had already won some victories in various parts of Britain and now advanced into northern Scotland, where, at Mons Graupius, he gained a significant victory over the Picts in battle.

Dark Side of Domitian

Then, in AD 85, Agricola was suddenly recalled from Britain. Whether he was on the brink of achieving the final conquest of Britain has been the subject of much speculation. One will never know. It appears that Domitian, so eager to prove himself a great conqueror, was, in fact, jealous of Agricola’s success. Agricola’s death in AD 93 is rumored to have been the work of Domitian by having him poisoned.

In a move to increase his power over the senate, Domitian proclaimed himself a ‘perpetual censor’ in AD 85, which granted him near unlimited power over the assembly. Domitian was more and more being understood as a tyrant who didn’t even refrain from having senators who opposed his policies assassinated. But his strict enforcement of the law also brought its benefits. Corruption amongst city officials and within the law courts was reduced. Seeking to impose his morals, he prohibited the castration of males and penalized homosexual senators.

Domitian’s administration is judged to have been sound and efficient, though at times pedantic – he insisted on spectators at public games being properly dressed in togas. Always worried about state finances, he at times displayed near neurotic meanness. But the finances of the empire were further organized to the point that imperial expenditure could at last be reasonably forecast. And under his rule, Rome itself became yet more cosmopolitan.

Domitian’s Stance on Religion

Domitian was especially rigorous in exacting taxes from the Jews, taxes which were imposed by the emperor (since Vespasian) for allowing them to practice their own faith (fiscus iudaicus). Many Christians were also tracked down and forced to pay the tax based on the widespread Roman belief that they were Jews pretending to be something else.

The circumstances surrounding the recall of Agricola and the suspicions that this had been done only for purposes of jealousy only further fueled Domitian’s hunger for military glory. This time, his attention turned to the kingdom of Dacia. In AD 85, the Dacians, under their king Decebalus, crossed the Danube in raids, which even saw the death of the governor of Moesia, Oppius Sabinus.

Domitian led his troops to the Danube region but returned soon after, leaving his armies to fight. At first, these armies suffered another defeat at the hands of the Dacians. However, the Dacians were eventually driven back, and in AD 89, Tettius Julianus defeated them at Tapae.

But in the same year, AD 89, Lucius Antonius Saturninus was proclaimed emperor by two legions in Upper Germany. One believes that much of Saturninus’ cause for rebellion was the increasing oppression of homosexuals by the emperor. Saturninus, being a homosexual himself, rebelled against the oppressor.

The Battle of Castellum

But Lappius Maximus, the commander of Lower Germany, remained loyal. At the following battle of Castellum, Saturninus was killed, and this brief rebellion was at an end. Lappius purposely destroyed Saturninus’ files in the hope of preventing a massacre. But Domitian wanted vengeance. On the emperor’s arrival, Saturninus’ officers were mercilessly punished.

Domitian suspected, most likely with good reason, that Saturninus had hardly acted on his own. Powerful allies in the senate of Rome more than likely had been his secret supporters. And so in Rome, now the vicious treason trials returned, seeking to purge the senate of conspirators.

Though after this interlude on the Rhine, Domitian’s attention was soon drawn back to the Danube. The Germanic Marcomanni and Quadi and the Sarmatian Jazyges were causing trouble. A treaty was agreed with the Dacians, who were all too happy to accept peace. Then, Domitian moved against the troublesome barbarians and defeated them. The time he spent with the soldiers on the Danube only further increased his popularity with the army.

In Rome, however, things were different. In AD 90, Cornelia, the head of the Vestal Virgins, was walled up alive in an underground cell after being convicted of ‘immoral behavior’. In Judaea, Domitian stepped up the policy introduced by his father to track down and execute Jews claiming descent from their ancient king David. But if this policy under Vespasian had been introduced to eliminate any potential leaders of rebellions, then with Domitian, it was pure religious oppression. Even among the leading Romans in Rome itself, this religious tyranny found victims. The consul Flavius Clemens was killed, and his wife Flavia Domitilla was banished for being convicted of ‘godlessness’. Most likely, they were sympathizers with Jews.

Domitian’s ever-greater religious zealotry was a sign of the emperor’s increasing tyranny. The senate, by then, was treated with open contempt by him. Meanwhile, the treason trials had so far cost the lives of twelve former consuls. Ever more senators were falling victim to allegations of treason. Members of Domitian’s own family were not safe from accusation by the emperor. Also, Domitian’s own praetorian prefects weren’t safe. The emperor dismissed both prefects and brought charges against them. But the two new praetorian commanders, Petronius Secundus and Norbanus, soon learned that allegations had been made against them, too. They realized they needed to act quickly in order to save their lives.

The Plot Against Domitian

It was the summer of AD 96 when the plot was hatched, involving the two praetorian prefects, the German legions, leading men from the provinces, and the leading figures of Domitian’s administration – even the emperor’s own wife, Domitia Longina. By now, it appears, everyone wanted to rid Rome of this menace.

Stephanus, an ex-slave of Flavius Clemens’ banished widow, was recruited for the assassination. Together with an accomplice Stephanus duly murdered the emperor. Though it involved a violent hand-to-hand struggle in which Stephanus himself also lost his life. (18 September AD 96)

The senate relieved that the dangerous and tyrannical emperor was no more, was, at last, in a position to make its own choice of ruler. It nominated a respected lawyer, Marcus Cocceius Nerva (AD 32-98), to take over the government. It was an inspired choice of great significance, which laid out the destiny of the Roman empire for some time to come. Domitian, meanwhile, was denied a state funeral, and his name was obliterated from all public buildings.

People Also Aks:

What was Emperor Domitian known for?

Domitian was the Roman Emperor from 81 to 96 CE. He was known for being one of the worst Roman emperors in history. His narcissism and suspicion control his thoughts and decisions, making his actions cruel and unjust.

Was Domitian a successful emperor?

Despite his controversial reign, Domitian left a lasting legacy. He is remembered as one of Rome’s most impressive builders and as a competent and effective ruler. However, his tyrannical behavior has also led to him being remembered as one of Rome’s most cruel and ruthless emperors.

Which emperor succeeded Domitian?

Nerva became emperor immediately after Domitian’s murder in 96 AD. He had a lifetime of service to Rome and its emperors and had served as consul twice, in 71 and 90 AD.

What did Emperor Domitian do to John?

According to the Golden Legend, during the persecution of the Christians under the Roman emperor Domitian, John was thrown into a vat of boiling oil. He emerged miraculously unharmed, even rejuvenated.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.