Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD 332 – 363

- Name: Flavius Magnus Magnentius

- Born in AD 332 at Constantinople.

- Became emperor in February AD 360.

- Died in Mesopotamia, 26 June AD 363.

Julian was born in AD 332 at Constantinople, the son of Julius Constantius, who was a half-brother of Constantine the Great. His mother was Basilina, the daughter of the governor of Egypt, who died shortly after his birth.

His father was killed in AD 337 in the murders of Constantine’s relatives by the three brother-emperors Constantine II, Constantius II and Constans, who sought to not only have their co-heirs Dalmatius and Hannibalianus, but so too all other potential rivals killed.

After this massacre Julian, his half brother Constantius Gallus, Constantine’s sister Eutropia and her son Nepotianus were the only remaining relatives of Constantine left alive, other than the three emperors themselves.

Constantius II placed Julian in the care of the eunuch Mardonius, who educated him in the classical tradition of Rome, thereby instilling in him a great interest for literature, philosophy and the old pagan gods. Following in these classical tracks, Julian studied grammar and rhetoric, until he was moved from Constantinople to Nicomedia by the emperor in AD 342. Constantius II evidently didn’t like the idea of a youth of Constantine’s blood being too close to the centre of power, even if only as a student. Soon after Julian was moved again, this time to a remote fortress at Macellum in Cappadocia, together with his half-brother Gallus. There Julian was given a Christian education. Yet his interest in the pagan classics continued undiminished.

For six years Julian stayed in this remote exile until he was allowed to return to Constantinople, although only to be moved back out of the city soon after by the emperor and being returned to Nicomedia once more in AD 351.

After the execution of his half-brother Constantius Gallus by Constantius II in AD 354, Julian was ordered to Mediolanum (Milan).

But permission was soon granted for him to move to Athens to continue his extensive studies.

In AD 355 he was already recalled. With trouble brewing in the east with the Persians, Constantius II sought someone to take care of the problems on the Rhine frontier for him.

So Julian in AD 355 was elevated to the rank of Caesar, was married with the emperor’s sister Helena and was ordered to take to the Rhine to repel invasions by the Franks and Alemanni.

Julian, though completely inexperienced in military matters, successfully recovered Colonia Aggripina by AD 356, and in AD 357 defeated a vastly superior force of Alemanni near Argentorate (Strasbourg).

Following this he crossed the Rhine and raided German strongholds, and gained yet further victories over the Germans in AD 358 and 359.

The troops quickly took to Julian, a leader who like Trajan endured the hardships of military life alongside the soldiers.

But also the general population of Gaul appreciated their new Caesar for the extensive tax cuts he introduced.

Did Julian prove to be a talented leader, then his abilities earned him no sympathies at the court of Constantius II. Whilst the emperor was suffering setbacks at the hands of the Persians these victories by his Caesar were seen only as embarrassments.

Constantius II jealousies were such that it is believed he was even forming plans to have Julian assassinated.

But the military predicament of Constantius II with the Persians required urgent attention. And so he demanded Julian to send some of his finest troops as reinforcements in the war against the Persians.

But the soldiers in Gaul refused to obey. Their loyalties lay with Julian and they saw this order as a an act of jealousy on behalf of the emperor.

Instead in February AD 360 they hailed Julian emperor.

Julian was said to be reluctant to accept the title. Perhaps he wanted to avoid a war with Constantius II, or perhaps it was the reluctance of a man who never sought to rule anyway. In any case, he can’t have possessed much loyalty to Constantius II, after execution of his father and half-brother, his exile in Cappadocia and the petty jealousies over his apparent popularity.

At first he sought to negotiate with Constantius II, but in vain. And so in AD 361 Julian set out for the east to meet his foe. Remarkably, he vanished into the German forests with an army of only about 3’000 men, only to reappear again on the lower Danube shortly after. This astounding effort was most likely made in order to reach the key Danubian legions as soon as possible to assure their allegiance in that knowledge that all European units would surely follow their example.

But the move proved unnecessary as news arrived that Constantius II had died of illness in Cilicia.

On his way to Constantinople Julian then officially declared himself a follower of the old pagan gods. With Constantine and his heirs having been Christian, and Julian having, while still under Constantius officially still adhered to the Christian faith, this was an unexpected turn of events.

It was his rejection of Christianity which gave him his name in history as Julian ‘the Apostate’.

Shortly after, in December AD 361, Julian entered Constantinople as the sole emperor of the Roman world. Some of Constantius II’s supporters were executed, others were exiled. But Julian’s accession was by no means such a bloody one as when the three sons of Constantine had began their reign.

The Christian church was now refused the financial privileges enjoyed under previous regimes, and Christians were excluded from the teaching profession. In an attempt to undermine the Christian position, Julian favoured the Jews, hoping they might rival the Christian faith and deprive it of many of its followers. He even considered the reconstruction of the Great Temple at Jerusalem.

Though Christianity had established itself too firmly in Roman society to be successfully dislodged by Julian’s means. His moderate, philosophical nature did not allow for violent persecution and oppression of the Christians and so his measures failed to make significant impact.

One might argue that if Julian had been a man of the fibre of Constantine the Great, his attempted return to paganism might have been more successful. A ruthless, single-minded autocrat who would have enforced his desired changes with bloody persecutions might have succeeded. For large parts of the ordinary population were still pagans. But this high-minded intellectual was not ruthless enough to use such methods.

Indeed, the intellectual Julian was a great writer, second only perhaps to the philosopher emperor Marcus Aurelius, composing essays, satires, speeches, commentaries and letters of great quality.

He is clearly Rome’s second ever philosopher-ruler, after the great Marcus Aurelius. But if Marcus Aurelius was weighed down by war and plague then, Julian’s greatest burden was to be that he belonged to a different age. Trained classically, learned in Greek philosophy he would have made a fine successor to Marcus Aurelius. But those days had gone, now this distant intellect seemed out of place, at odds with many of his people, and certainly with the Christian elite of society.

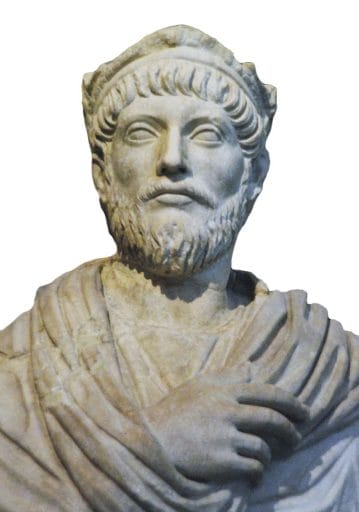

His appearance only further reinforced the image of a ruler of a bygone age. In a time when Romans were clean shaven, Julian wore an old-fashioned beard reminiscent of Marcus Aurelius. Julian was of athletic, powerful build. Though vain and prone to listen to flattery, he was also wise enough to allow advisors to correct him where he made mistakes.

As head of government he proved an able administrator, seeking to revive the cities of the eastern part of the empire, which had suffered in recent times and had begun to decline.

Measures were introduced to limit the effects of inflation on the empire and attempts were made to reduce bureaucracy.

Like others before him, Julian also cherished the thought of one day defeating the Persians and annexing their territories into the empire.

In March AD 363 he left Antioch at the head of sixty thousand men. Successfully invading Persian territory, he had by June driven his forces as far as the capital Ctesiphon. But Julian deemed his force too small to venture on capturing the Persian capital and instead retreated to join with a Roman reserve column.

Though on 26 June AD 363 Julian the Apostate was hit by an arrow in a skirmish with Persian cavalry. Though a rumour claimed he was stabbed by a Christian among his soldiers. Whatever the cause for the injury, the wound did not heal and Julian died.

At first he was, as he had wished, buried outside Tarsus. But later his body was exhumed and taken to Constantinople.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.