Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

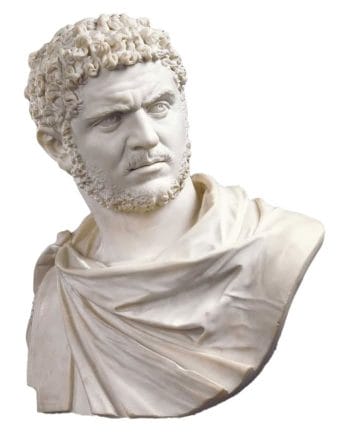

Life: AD 188 – 217

- Name: Lucius Septimius Bassianus

- Born on 4 April AD 188 at Lugdunum (Lyons).

- Consul AD 202, 205, 208, 213.

- Became co-emperor in 4 February AD 211.

- Wife: Publia Fulvia Plautilla.

- Died near Sirmium, 8 April AD 217.

Caracalla was born on 4 April AD 188 in Lugdunum (Lyons), being named Lucius Septimius Bassianus. His last name was given him in honour of the father of his mother Julia Domna, Julius Bassianus, high priest of the sun god El-Gabal at Emesa.

The nickname Caracalla was given to him, as he tended to wear a long Gallic cloak of that name.

In AD 195, his father, emperor Septimius Severus, declared him Caesar (junior emperor), changing his name to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. This announcement should spark off a bloody conflict between Severus and Clodius Albinus, the man who had been named Caesar previously.

With Albinus defeated at the battle of Lugdunum (Lyons) in February AD 197, Caracalla was made co-Augustus in AD 198. In AD 203-4 he visited his ancestral north Africa with his father and brother.

Then in AD 205 he was consul alongside his younger brother Geta, with whom he lived in bitter rivalry.

From AD 205 to 207 Severus had his two quarrelsome sons live together in Campania, in his own presence, in order to try and heal the rift between them. However the attempt clearly failed.

In AD 208 Caracalla and Geta left for Britain with their father, to campaign in Caledonia. With his father ill, much of the command lay with Caracalla.

When on campaign Caracalla was said to have been eager to have seen the end of his sick father. There is even a story of him trying to stab Severus in the back while the two were riding ahead of the troops. This however seems very unlikely. Knowing Severus’ character, Caracalla would not have survived such failure.

However, a blow was dealt to Caracalla’s aspirations when in AD 209 Severus did also raise Geta to the rank of Augustus. Evidently their father intended them to rule the empire together.

Septimius Severus died in February AD 211 at Eburacum (York). On his deathbed he famously advised his two sons to get on with each other and to pay the soldiers well, and not to care about anyone else.

The brothers though should have a problem following the first point of that advice.

Caracalla was 23, Geta 22, when their father died. And felt such hostility towards each other, that it bordered on outright hatred.

Immediately after Severus’ death there appeared to have been an attempt by Caracalla to seize power for himself. If this was truly an attempted coup is unclear. Far more it appears Caracalla tried to secure power for himself, by outright ignoring his co-emperor.

He conducted the resolution of the unfinished conquest of Caledonia by himself. He dismissed many of Severus’ advisors who would have sought to also support Geta, following Severus’ wishes.

Such initial attempts at ruling alone were clearly meant to signify that Caracalla ruled, whereas Geta was emperor purely by name (a little like emperors Marcus Aurelius and Verus had done earlier).

Geta however would not accept such attempts. Neither would his mother Julia Domna. And it was her who forced Caracalla to accept joint rule.

With the Caledonian campaign at an end the two then headed back for Rome with the ashes of their father. The voyage back home is noteworthy, as neither would even sit at the same table with the other for fear of poisoning.

Back in the capital, they tried to live alongside each other in the imperial palace. Yet so determined were they in their hostility, that they divided the palace in two halves with separate entrances. The doors which might have connected the two halves were blocked.

More so, each emperor surrounded himself with a large personal bodyguard.

Each brother sought to gain the favour of the senate. Either one sought to see his own favourite appointed to any official office which might become available. They also intervened in court cases in order to help their supporters. Even at the circus games, they publicly backed different factions.

Worst of all attempts apparently were made from either side to poison the other.

Their bodyguards in a constant state of alert, both living in everlasting fear of being poisoned, Caracalla and Geta came to the conclusion that their only way of living as joint emperors was to divide the empire. Geta would take the east, establishing his capital at Antioch or Alexandria, and Caracalla would remain in Rome.

The scheme might have worked. But Julia Domna used her significant power to block it. It is possible that she feared, if they separated, she could no longer keep an eye on them. Most likely though she realized, that this proposal would lead to outright civil war between east and west.

Alas, in late December AD 211 he pretended to seek to reconcile with his brother and so suggested a meeting in the apartment of Julia Domna. Then as Geta arrived unarmed and unguarded, several centurions of Caracalla’s guard broke through the door and cut him down. Geta died in his mother’s arms.

What, other than hate, drove Caracalla to the murder is unknown. Known as an angry, impatient character, he perhaps simply lost patience. On the other hand, Geta was the more literate of the two, often surrounded by writers and intellects. It is therefore well likely that Geta was making more of an impact with senators than his tempestuous brother. Perhaps even more dangerous to Caracalla, Geta was showing a striking facial similarity to his father Severus. Had Severus been very popular with the military, Geta’s star might have been on the rise with them, as the generals believed to detect their old commander in him.

Hence one could speculate that perhaps Caracalla opted to murder his brother, once he feared Geta might prove the stronger of the two of them.

Many of the praetorians didn’t feel at all comfortable with the murder of Geta. For they remembered that they had sworn allegiance to both emperors. Caracalla though knew how to win their favour. He paid each man a bonus of 2’500 denarii, and raised their ration allowance by 50%.

If this won over the praetorians then, a pay rise from 500 denarii to 675 (or 750) denarii to the legions assured him of their loyalty.

Further to this Caracalla then began hunting down any supporters of Geta. Up to 20’000 are believed to have died in this bloody purge. Friends of Geta, senators, equestrians, a praetorian prefect, leaders of the security services, servants, provincial governors, officers, ordinary soldiers – even charioteers of the faction Geta had supported; all fell victim to Caracalla’s vengeance.

Suspicious of the military, CAracalla also now rearranged the way legions were based in the provinces, so that no single province would be host to more than two legions. Clearly this made revolt by provincial governors much more difficult.

However harsh, Caracalla’s reign should not only be known for its cruelty. He reformed the monetary system and was an able judge when hearing court cases. But first and foremost of his acts is one of the most famous edicts of antiquity, the Constitutio Antoniniana. By this law, issued in AD 212, everyone in the empire, with the exception of slaves, was granted Roman citizenship.

Then in AD 213 CAracalla went north to the Rhine to deal with the Alemanni who were once more causing trouble in the Agri Decumates, the territory covering the springs of the Danube and Rhine. It was here that the emperor showed a remarkable touch in winning the sympathy of the soldiers. Naturally his pay rises had made him popular. But when with the troops, he marched on foot among the ordinary soldiers, ate the same food ad even ground his own flour with them.

The campaign against the Alemanni was only a limited success. Caracalla defeated them in battle near the river Rhine, but failed to win a decisive victory over them. And so he chose to change tactics and instead sued for peace, promising to pay the barbarians an annual subsidy.

Other emeprors would have paid dearly for such a settlement. To buy the opponent off was largely seen to be a humiliation for the troops. (Emperor Alexander Severus was killed by mutinous troops in AD 235 for the same reason.) But it was Caracalla’s popularity with the soldier’s which allowed him to get away with it.

In AD 214 Caracalla then headed east, through Dacia and Thrace to Asia Minor (Turkey).

It was at this point that the emperor began to have delusions of being Alexander the Great. Gathering an army as he passed through the military provinces along the Danube, he reached Asia Minor at the head of a large army. One part of this army was a phalanx consisting of 16’000 men, in armour of the style of Alexander’s Macedonian solders. The force was also accompanied by many war elephants.

Statues of Alexander were ordered to be sent back home to Rome. Pictures were commissioned, which bore a face which was half Caracalla, half Alexander. Because Caracalla believed that Aristotle had had some part in Alexander’s death, Aristotelian philosophers were persecuted.

The winter of AD 214/215 was passed at Nicomedia. In May AD 215 the force reached Antioch in Syria. Most likely leaving his great army behind at Antioch, Caracalla now went on to Alexandria to visit the tomb of Alexander.

It is not known what precisely occurred next in Alexandria, but somehow Caracalla grew enraged. He set the troops which were with him on the people of the city and thousands were massacred in the streets.

AFter this gruesome episode in Alexandria, Caracalla headed back to Antioch, where in AD 216 no fewer than eight legions were waiting for him. With these he now attacked Parthia, which was preoccupied with a bloody civil war. The frontiers of the province of Mesopotamia were pushed further east. Attempts though to overrun Armenia failed. Instead Roman troops marauded across the Tigris into Media and then finally withdrew to Edessa to spend the winter there.

Parthia was weak and had little with which it could respond to these attacks. Caracalla sensed his chance and planned further expeditions for the next year, most likely hoping to make some permanent acquisitions to the empire. Though it was not to be.

The emperor might have enjoyed popularity with the army, but the rest of the empire still hated him.

It was Julius Martialis, an officer in the imperial bodyguard, who murdered the emperor on a voyage between Edessa and Carrhae, when he relieved himself out of sight from the other guards.

Martialis himself was killed by the emperor’s mounted bodyguard. But the mastermind behind the murder was the commander of the praetorian guard, Marcus Opelius Macrinus, the future emperor.

Caracalla was only 29 at his death. His ashes were sent back to Rome where they were laid to rest in the Mausoleum of Hadrian. He was deified in AD 218.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.