Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD 145 – 211

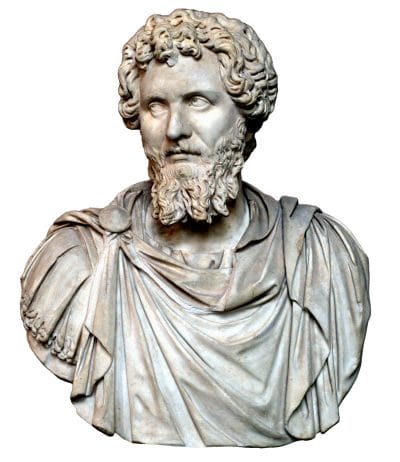

- Name: Lucius Septimius Severus

- Born on 11 April AD 145 at Lepcis Magna.

- Consul AD 190, 193, 194, 202.

- Became emperor in 9 April AD 193.

- Wife: (1) Pacia Marciana, (2) Julia Domma (two sons; Septimius Bassianus, Publius Septimius Geta).

- Died in Ebucarum (York), 4 February AD 211.

Lucius Septimius Severus was born on 1 April AD 145 at Lepcis Magna in Tripolitania.

His family was of African descent. His paternal great-grandfather, who had moved from Lepcis Magna to Italy and become an equestrian, was most likely of Punic origin and his mother, Fulvia Pia, was from a family which had moved from Africa to Italy.

Little is known of Severus’ father, Publius Septimius Geta, other than that he had two cousins who became consuls.

Severus was a small man, but powerfully built. Though in old age he was to became very weak and ridden with gout. He was not very well educated, he spoke little in public. And so too, he is renowned for his cruelty and ruthlessness. The Historian Cassius Dio says about him, ‘Severus was careful of everything that he desired to accomplish, but careless of what was said about him.

Shortly after his eighteenth birthday Severus arrived in Rome and was appointed senator by Marcus Aurelius in about AD 175. Thereafter he became governor of Gallia Lugdunensis and Sicily and, towards the end of Commodus’ reign, he was made consul in AD 190.

Then as the plot thickened to kill Commodus, an African friend of Severus’, the praetorian prefect Laetus, placed people he could rely on in key positions of the empire. And so his friend Severus was put in place as governor of Upper Pannonia.

The plot succeeded and brought Pertinax to power. But soon after Pertinax was murdered and Didius Julianus bought the throne from the praetorian guard. Laetus was executed for his involvement with the murder of Commodus.

The three main people who had been placed in powerful positions by Laetus all found it was time to act. The three were Severus, Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus.

Severus had himself acclaimed emperor by his troops at Carnuntum in AD 193. Pescennius Niger was hailed emperor by his troops in the east. Clodius Albinus meanwhile didn’t have himself hailed emperor, but he was undoubtedly waiting in the wings, preparing for the right moment.

But Clodius Albinus, commander of the legions in Britain and with much support in the senate, was approached by Severus, who granted him the position of Caesar (junior emperor). This junior position clearly implied that Clodius Albinus was marked out as Severus’ successor, or so at least Albinus was led to believe. It was a shrewd political trick to buy off Clodius, as it now left Severus to advance rapidly on Rome. Advancing with no less than 16 legions under his command, opposition simply crumbled before him.

Severus ignored all of Julianus’ threats and pleas, and shortly before his army’s arrival at Rome, Julianus was indeed sentenced to death by the senate and was thereafter killed in his deserted palace.

Once he arrived in Rome, Severus had those involved in the murder of Pertinax executed. Meanwhile the praetorian guard which had proved such a threat to any emperor was disbanded, and its members were banished from Rome. Instead he put in its place a force double in size, made up of men drawn from his army, especially the Danubian legions.

Severus also trebled the number of the city cohorts (the police of Rome) and doubled the fire brigade (vigiles) in order to increase the city’s security.

To raise morale in the army, the institution which had clearly established him on the throne, he increased their pay from three hundred to five hundred denarii a year.

Having firmly established himself at Rome and knowing his western borders toward Albinus secured with his grant of the caesarship, Severus was free to move eastwards and deal with Pescennius Niger. In AD 194 Severus Severus crushed Niger’s forces at Issus on the very plain on which Alexander the Great had defeat Darius some 500 years earlier.

With his opponent dead, Severus could now further stamp his authority on the east. The supporters of Niger were harshly punished, many of them fleeing to the Parthians, who had helped Niger in his fight. In order that no future governors of Syria should take up the idea of proclaiming themselves emperor, the powerful province was split in two; Coele-Syria and Phoenicia.

To follow up on his success and punish the Parthians, Severus lead a punitive campaign against the Osrhoeni of Mesopotamia and other Parthian vassals across the border.

His rule of the east secured, Severus now turned his attention to Clodius Albinus. First he declared his elder son Caracalla to be Caesar and therefore his heir late in AD 195. This was clearly a slap in the face to Albinus, who understood himself successor to the throne.

In effect it was a veiled challenge and Albinus took it up. In AD 196 he too had himself hailed emperor by his troops and then set across the channel into Gaul with 40’000 men, collecting more forces as he moved on towards Rome.

Severus, having only briefly returned to Rome in AD 196-7, in January AD 197 set out for his power base on the Danube. From there in Pannonia he began a march west, through Noricum, Raetia, Upper Germany and Gaul, gathering troops as he went.

The huge armies tentatively met at first at Tinurtium. Severus achieved victory, but it proved of little meaning. The full battle was still to follow at Lugdunum (Lyons) on 19 February AD 197. It was a very close battle. At one point an advance by one section of Albinus’ troops was so close to Severus, he was thrown from his horse and decided to throw away his cloak marking him out as emperor in an attempt to conceal his identity. But this advance was eventually pushed back, saving the emperor.

The battle still hung in the balance for a long time, but alas Severus’ side won.

Clodius Albinus fled into the town of Lugdunum (Lyons) seeking to escape. But discovering that escape was impossible, he killed himself (or he was stabbed).

What followed was very revealing about the man who was now the uncontested emperor of the Roman empire. Severus had Albinus stripped corpse laid out on the ground, so that he he could ride over it and trample it with his horse. Thereafter Albinus’ head was severed and sent to Rome. His body, along with those of his wife and sons, was flung into the Rhine.

Albinus’ province Britain was thereafter, like Niger’s Syrian province, divided into two parts; Britannia Superior and Inferior.

If Albinus had enjoyed support in the senate, then Severus now clamped down on those supporters. He ruthlessly put to death 29 senators and numerous equestrians in Rome.

This cruelty and vindictiveness earned Severus the nickname ‘the Punic Sulla’, referring to his African origin and the notoriously vengeful dictator of the Roman republic.

Now, Severus attentions once more turned back to Parthia. Had his earlier expedition into Parthia been a brief affair, most likely as he felt he had to return to the west to take care of Albinus, then now he was undisputed ruler and had no such restrictions.

Parthia, so he decided, now should suffer his wrath for intervening in favour of Pescennius Niger.

No doubt, there were also other considerations. Severus was in essence a military man. And he and his generals naturally sought military glories.

The war was brief, for Parthia was weak at the time. By the end of AD 197 the capital Ctesiphon was captured. Once again Severus ruthlessness shows in the fact that all the men were killed, and the women and children (roughly 100’000) were sold into slavery.

Thereafter Mesopotamia was once more annexed as a province of the Roman empire.

But Severus should not have it all his way. The strategic fortress city of Hatra was besieged twice without success, making it clear that not all of Mesopotamia was in Roman hands.

The business of government was largely conducted on Severus’ behalf by his praetorian prefects, who quickly became loathed by the public. Most notorious of all was the close friend of the emperor, prefect Gaius Fulvius Plautianus, who didn’t take long to gain a reputation for abuses of power and utter cruelty. There was even a rumour that for his daughter Publia Fulvia Plautilla, who was wed to the emperor’s son Caracalla, he had grown men castrated to be her eunuch-servants.

Caracalla, who had been made co-emperor in early AD 198, resented being married to Plautianus’ daughter, is said to perhaps have arranged his assassination. Things are unclear. Accounts differ. Either Caracalla ordered three officers to carry a false warning to Severus that he and Caracalla were in danger of Plautianus, or they actually was a real plot. Whichever version is true, Severus acted swiftly and had his powerful prefect executed.

Thereafter the corpse was flung onto the street, where the public took out its anger on the hated figure.

Throughout his reign Severus was one of the outstanding imperial builders. He restored a very large number of ancient buildings – and inscribed on them his own name, as though he had erected them. His home town Lepcis Magna benefited in particular. But most of all the famous Triumphal Arch of Severus at the Forum of Rome bears witness to his reign.

His health fading and weak from gout, Severus woudl set out one last time on military campaign. This time it was Britain which demanded the emperor’s attention. The Antonine Wall had never really acted as a perfectly successful barrier to the troublesome barbarians to the north of it. By this time it had in fact been virtually abandoned, leaving the British provinces vulnerable to attack from the north. In AD 208 Severus left for Britain with his two quarrelsome sons. Large military campaigns now drove deep into Scotland but didn’t really manage to create any lasting solution to the problem.

It is worth mentioning though that there is a tale by which Caracalla was said to have tried to stab Severus in the back at one point, when Severus and his son were riding ahead of the army. But Severus was supposedly warned by shouts from the soldiers behind. However, this tale seems to have little credibility as it otherwise would have seemed impossible for Caracalla to have remained heir thereafter. With the campaigns to conquer the Caledonian territories not being of any lasting success, Hadrian’s Wall instead was reconstructed, this time in stone, to defend the frontier.

Alas Severus fell ill at Eburacum (York), where he died at the age of sixty-six (4 February AD 211).

‘Keep on good terms with each other,’ is said to have been his last advice to his sons, ‘be generous to the soldiers, and take no heed of anyone else !”

His sons Caracalla and Geta brought an end to any military campaigns into the Scotland which were still underway and then set out home, carrying the ashes of their father to Rome, where they were laid to rest in the Mausoleum of Hadrian. Soon after he was deified by the senate.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.