Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

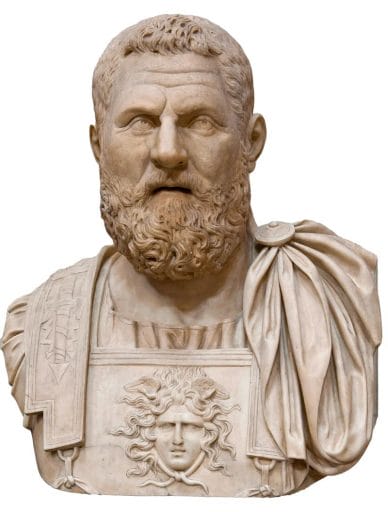

Life: AD 126 – 193

- Name: Publius Helvius Pertinax

- Born on 1 August AD 126 at Alba Pompeia in Liguria.

- Consul AD 120, 139, 140, 145.

- Became emperor in 1 January AD 193.

- Wife: Flavia Titiana (one son; Publius HelviusPertinax; one daughter; name unknown.

- Died in Rome, 28 March AD 193.

- Deified 1 June AD 193

Publius Helvius Pertinax was born at Alba Pompeia in Liguria in AD 126. His father was a freed slave, who allegedly named his son Pertinax to commemorate his own perseverance in the timber or wool trade in which he appeared to achieve some success.

His father’s wealth assured Pertinax a sound classical education. He thereafter went on to be a teacher. But by AD 161, at 35 years of age, he had had enough of the low wages of a teacher and instead decided on a military career.

Being a well-educated man, Pertinax was not to start as a simple soldier, but as the commander of a cohort of Gallic soldiers in Syria. If he joined the military at a late age, then he made up for it by having talent for the job. In a remarkable achievement he achieved promotion to the rank of military tribune very soon. This took him to the VI Legion ‘Victrix’ in Eburacum (York) in Britain, where he once again appears to have excelled.

Having evidently made a name for himself he now became a civilian for a while in order to hold office. First, in AD 168, he acted as procurator of equestrian rank in Italy, being in charge of the alimenta, the welfare scheme for the poor, along the Via Aemilia.

After this he held the procuratorship again, this time in the province of Dacia.

Then he was called back to the military to serve in Marcus Aurelius’ wars along the Danube, as the commander of vexillationes, a troop of men detached from their legion and operating as a separate unit, in Pannonia. In this command, Pertinax saw much action against the Germans.

Once more Pertinax must have made a very good job of it. He was promoted to senatorial rank and acted as praetor in Raetia with the command of a legion (AD 171).

Now a high-flyer and having evidently won the goodwill of Marcus Aurelius, he became consul in AD 174 or 175.

He also appeared to be instrumental in putting down the revolt of Cassius in Syria in AD 175. Further he served as governor of Upper Moesia, Lower Moesia, Dacia, and in AD 181 of Syria .

With Commodus Pertinax at first fell from grace due to his good relations with some of the conspirators of AD 182. But once a mutiny of the army of Britain called for an experienced and reliable military commander, Pertinax was recalled. He served there from AD 185 to 187.

Having so regained the trust of the emperor, Pertinax was given the post of proconsul of province of Africa in AD 188. Then, once more for his ability to keep difficult situations under control, Pertinax was made city prefect of Rome in AD 189, winning a second consulship in AD 192.

It is highly unlikely that Pertinax didn’t know of the plot to kill Commodus on 31 December AD 192. And so too, did he no doubt know that he was intended by the conspirators to succeed the deranged emperor.

On the night of the murder, the praetorian commander Laetus (who had organized the plot) asked Pertinax to accept the throne. Pertinax then, in the same night, made his way to the praetorian camp where he offered the guardsmen the large sum of 12’000 sesterces per man as a bonus.

The night not yet over, he then set out to the senate where, in a nocturnal meeting, he was warmly by the senators who were relieved to see the nightmarish rule of Commodus finally at an end.

And so the son of a freed slave had made it to the throne of the Roman empire.

Only a mediocre public speaker, Pertinax was first and foremost a gritty old soldier. He was heavily built, had a pot belly, although it was said, even by his critics, that he possessed the proud air of an emperor.

He possessed some charm, but was generally understood to be a rather sly character. He also acquired a reputation for being mean and greedy. He apparently even went as far as serving half portions of lettuce and artichoke before he became emperor. It was a characteristic which would not serve him well as an emperor.

When he took office, Pertinax quickly realized that the imperial treasury was in trouble. Commodus had wasted vast sums on games and luxuries. If the new emperor thought that changes would need to be made to bring the finances back in order he was no doubt right. But he sought to do too much too quickly. In the process he made himself enemies.

The gravest error, made at the very beginning of his reign, was to decide to cut some of the praetorian’s privileges and that he was going to pay them only half the bonus he had promised.

Already on 3 January AD 193 the praetorians tried to set up another emperor who would pay up. But that senator, wise enough to stay out of trouble, merely reported the incident to Pertinax and then left Rome.

The ordinary citizens of Rome however also quickly had enough of their new emperor. Had Commodus spoilt them with lavish games and festivals, then now Pertinax gave them very little.

And a truly powerful enemy should be the praetorian prefect Laetus. The man who had after all put Pertinax on the throne, was to play an important role in the emperor’s fate. It isn’t absolutely clear if he sought to be an honest advisor of the emperor, but saw his advise ignored, or if he sought to manipulate Pertinax as his puppet emperor. In either case, he was disappointed.

And so as Pertinax grew ever more unpopular, the praetorians once more began to look for a new emperor. In early March, When Pertinax was away in Ostia overseeing the arrangements for the grain shipments to Rome, they struck again. This time they tried to set up one of the consuls, Quintus Sosius Falco.

When Pertinax returned to Rome he pardoned Falco who’d been condemned by the senate, but several praetorians were executed. A slave had given them away as being part of the conspiracy.

These executions were the final straw. On 28 March AD 193 the praetorians revolts.

300 hundred of them forced the gates to the palace. None of the guards sought to help their emperor.

Everyone, so it seemed, wanted rid of this emperor. So, too, Laetus would not listen as Pertinax ordered him to do something. The praetorian prefect simply went home, leaving the emperor to his fate.

Pertinax did not seek to flee. He stood his ground and waited, together with his chamberlain Eclectus. As the praetorians found him, they did not discover an emperor quivering with fear, but a man determined on convincing them to put down their weapons. Clearly the soldiers were over-awed by this brave man, for he spoke to them for some time. But eventually their leader found enough courage to step forwards and hurl his spear at the emperor. Pertinax fell with the spear in his chest. Eclectus fought bravely for his life, stabbing two, before he two was slain by the soldiers.

The soldiers then cut off Pertinax’ head, stuck it on a spear and paraded through the streets of Rome.

Pertinax had ruled for only 87 days. He was later deified by Septimius Severus.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.