Last Updated on December 18, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Roman clothing owed much to that of ancient Greece, but it had distinct forms of its own.

In all the ancient world, first and foremost clothes needed to be simple. As for possible materials there was only really one. Wool, although to some extent linen was also available.

The needles of the day were coarse and unwieldy by modern standards. Hence any stitching or sewing was kept to a minimum.

This of course also ruled out button holes, and meant that any kind of clothing was held together either with fastenings such as broaches or clasps.

Underwear

As undergarments Romans would wear a simply loin cloth knotted on each side. This garment appeared to have several names. The most probable explanation for this is that they varied in shape.

They were the subligar, subligaculum, campestre, licium and cinctus.

Women would also wear a simple brassière in the form of a band, tightly tied around the body, either across the bust and under clothing (fascia), or under the bust and over clothing (strophium, mammillare, cingulum).

Undergarments are believed to generally have been of linen. Spanish, Syrian and Egyptian linen was deemed of the finest quality.

The Tunic

The most basic garment in Roman clothing was the tunic (tunica). It was the standard dress of Rome. For most Romans and slaves the tunic would be the entire clothing they dressed in before setting foot outdoors.

The male tunic would generally reach roughly to the knees, whereas women’s tunics would generally be longer, some reaching to the ground. Female tunics often also had long sleeves. However, it took until the second or third century AD for long sleeves to become acceptable for men. Until then it was perceived as highly effeminate to be wearing one.

Cold weather would likely see Romans wear two or three tunics to keep warm. In that case the tunics nearest the body, functioning as a vest, would be the subucula. The next layer would be the intusium or supparus. Emperor Augustus, who was of a rather frail constitution, was known to wear as many as four tunics in winter.

There was some formal differences in tunics which denoted social rank.

A purple stripe worn on the tunic was called a clavus and indicated membership to a particular order:

- the latus clavus (or laticlavium) denoted senators.

- the angustus clavus was the mark of the equestrian order.

So a senator could wear a tunic featuring a vertical broad purple stripe down the centre. An equestrian could wear a tunic featuring two vertical narrow purple stripes on either side of the tunic.

It is worth mentioning the tunica palmata which was a brightly coloured tunic embroidered with palm leaves and was worn by the triumphator during his triumph, or possibly by other dignitaries at other, very exceptional occasions.

The richest form of the long-sleeved tunic, the dalmatica, in many cases replaced the toga altogether in the later years of empire. In the very same age, due to the influence of Germanic soldiers dominating the ranks of the army, long, close-fitting trousers were widely worn.

The Toga

The toga was allowed to be worn only by free Roman citizens. Foreigners, or even exiled citizens, could not appear in public wearing a toga.

If in the early days the toga was worn directly on the naked body, then later a simple tunic was added, tied at the waist with a belt.

There were some old families with ancient ancestry who insisted on continuing the tradition of dressing without a tunic, but their fellow Romans understood them somewhat eccentric.

Basically the toga was a large blanket, draped over the body, leaving one arm free.

Through experiments historians have concluded that the vast blanket took the form of a semi circle. It was along the straight edge the purple stripe of a senator’s toga praetexta ran.

Usually the toga spanned between 2 ½ and 3 meters long (though apparently up to 5 ½ metres long in some cases) and at its widest point it will have been up to 2 metres wide.

No doubt keeping such a cumbersome item of clothing on one’s body, and looking elegant, will have been fraught with practical problems as one moved about, sat down and got up again.

In some cases lead weights were sewn into the hem to help keep the garment in place. In order to help the toga drape more gracefully, slaves were known to place pieces of wood in the folds the previous evening.

The toga was made of wool. The rich had the luxury of choice of what kind of wool they sought to wear. Of Italian wares, the wool of Apulia and Tarentum were deemed the best. Meanwhile wool from Attica, Laconica, Miletus, Laodicea and Baetica were deemed of the finest quality of all.

Boys of reasonably wealthy families already would be expected to wear the toga. In their case, the garment oddly shared its name with that of the senators, the toga praetexta. On formally becoming a man, usually around his 16th birthday, the young Roman would then dispense with the toga praetexta and instead wear the simple, white toga of the Roman citizen, known as the toga virilis, toga pura or toga libera. It is worth mentioning that the white colour of the toga was prescribed by law.

There may be an explanation why a boy’s toga was deemed a toga praetexta. It may have traditionally born a purple hem. So too may the stola of girl until marriage.

This obviously would have been cheap imitation purple and not the real Tyrian purple dye.

In times of the republic, it was simply deemed improper for a Roman citizen of note to be seen in public without his toga.

After all, anyone who didn’t want to be seen as a slave or a workman in Rome had to be seen in a toga. The only exception for this was the festival of the saturnalia when everyone, including the magistrates, left their toga at home.

Some early emperors were very keen to maintain the republican traditions of a toga-wearing public, but gradually it began to fade from use, being worn only as formal dress at the law courts, the theatre, the circus or at the imperial court.

It is also known that many politicians campaigning for public office would go as far as whitening their toga with chalk in order to stand out more from the crowd. In fact this is the very reason for the name. In Latin candida stands for white. So the candidates were ‘the white ones’. The use of the word has survived unto this day in the English language.

There are certain types of toga which are of note.

The toga picta was a brightly coloured and richly embroidered garment and was chiefly worn by victorious military commanders on their triumph through the streets of Rome. The toga palmata, alike the tunica palmata richly embroidered and decorated with a palm leaf pattern, was a type of toga picta.

The toga trabea was ceremonial toga of various colours. It was either wholly purple (if meant to decorate the statues of deities) or featuring purple stripes for kings, augurs and some priests.

Finally, the toga pulla or toga sordida was of dark colour and was worn when in mourning.

At dinner parties and in private the toga was simply deemed too impractical and so on such occasions it was often replaced by the synthesis, a sort of dressing gown. Else one simply wore a tunic.

Textiles and Dyes

Status was evidently all-important in Rome. Given that clothes were a simple way of expression such status, it is little surprise that rich families had slaves trained as tailors (vestiarii, paenularii).

Trade guilds existed for the professional tailors, dyers and fullers, indicating that there existed a substantial industry.

The fullers of course are famed for their large earthenware bowls which they kept at their gates into which citizens caught short could relieve themselves. The gesture was of course not entirely selfless. Fullers were dependant on the ammonia they gathered from urine as a natural detergent.

Of the greatest importance when considering the dying of textiles was of course Tyrian purple. Tyrian purple dye was one of the most costly commodities available in the ancient world.

The dye was gained from the glandular fluids of certain types of sea snails in the eastern Mediterranean, known collectively as murex snails.

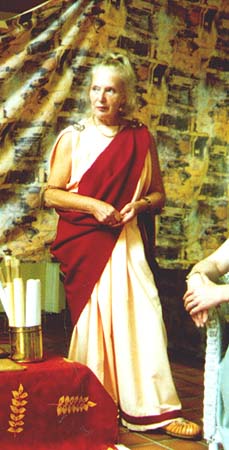

Women’s Dress

Fewer restrictions by laws, customs and traditions existed on the dress of women. If initially is believed to have been largely white, like the dress of men, then didn’t appear to stay so for long. Female clothes instead being of almost any colour.

The basic female garment was the stola. It was essentially a long tunic reaching to the ground. If could have long or short sleeves, or be entirely sleeveless.

The stola was generally worn over another long tunic, the tunica interior.

It was often the case that the stola therefore was shorter than the under tunic in order to show the layers of garment (which invariably was a display of wealth and status).

Another display of wealth could be a wide ornamental border (instita) on the lower hem of either the under tunic or the stola.

As an over garment women in the early days of the republic wore the ricinium, a simple square cloak, covering the shoulders. But later the ricinium was replaced by the palla.

It is perhaps easiest to describe the palla as a draped cloak similar to the toga, albeit smaller and much less unwieldy.

There seems to have been no specific size or shape that specified a palla.

So it could range from a large garment which draped around the body to something no more significant than a scarf.

Silk clothing was available to the rich, but was solely used for female vestments, as for men it was deemed utterly effeminate until the late empire, when the courtiers of the 4th century dressed in elaborately embroidered silk robes.

Children

It is fair to assume that children, especially those not borne to rich families spent their time in simple, belted tunics.

Children wore an amulet called the bulla. Boys would wear it until reaching their manhood, usually around the age of sixteen. Girls would wear it until they married.

Cloaks

Cloaks and other over garments were used to protect against bad weather. A variety are known, at times worn over the toga itself, but more often replacing it.

If various kinds of cloaks are known by name, it is today quite hard to discern where the precise differences between these garments are to be found as little more than their name is known.

The pallium was worn over the tunic or the toga. This seems possibly to have been quite a colourful decorated item, hence possibly an outdoor vestment of the wealthy.

The lacerna was originally a military cloak, but during the empire it begun to be extensively worn by the middle class. The wealthier people tended to wear brightly coloured lacerna, whereas the poor wore cheaper dull, dark ones.

The paenula was a very simple type of cloak, used especially as protection against bad weather. It was a cloak the Romans probably adapted form their Gallic neighbours early on.

It was put on by simply pulling one’s head through the central hole and was normally fitted with a hood. They could be made of either leather (paenula scortae), or very heavy felt (paenula gausapina).

The paenula was worn by both men and women.

The laena (also called duplex) was thick, round cloak which was folded double at the shoulders and was generally of heavy material, much like the military cloak, the sagum.

The sagum appears to have been worn by soldiers and officers alike. The sagulum most likely being a shorter version of the full sagum, reaching to the hips, rather than to the knees.

The paludamentum was a particular red cloak which in republican times was worn solely by the commander in chief (ergo, it would be available only to a consul or dictator). He was handed the cloak as part of the ceremony of inauguration as military commander on the Capitoline Hill.

Once the emperors ruled, the paludementum became a symbol of imperial power and was worn, highly ornamented, only by the emperor.

The poor wore short and dark laena, whereas the wealthy would wear brightly coloured one to cover their shoulders at banquets during the cold season.

In many cases a hood, the cucullus, would be sewn to a cloak. In fact there may have been a hooded cloak called cucullus.

Other such hooded cloaks were the bardocullus, birrus, and the caracalla, a heavy hooded cloak.

Footwear

Roman footwear showed little distinction between male and female. One usually wore sandals tied round the ankle with thin strips of leather.

There were three main types of footwear:

- The calcei were the standard outdoor footwear for a Roman and formed part of the national dress with the toga. It was a soft leather shoe, generally speaking a cross between a shoe and a sandal.

- Sandals (soleae, crepidae or sandalia) were generally regarded as indoor footwear. It was as improper to be seen in public wearing sandals outdoors as it was to visit your host’s banquet in anything other. Hence a wealthy Roman would have a slave accompany him to a banquet, to carry his sandals, where he would change into them.

- The third general type of footwear was a pair of slippers (socci), which were also meant for indoor use.

There were of course other types of footwear. The pero was a simple piece of leather wrapped around the foot, the caliga was the hob-nailed military boot/sandal and the sculponea was a wooden clog, worn only by poor peasants and slaves.

Beards and Hairstyles

The tradition of intricately groomed beards was quite common among the Greeks and Etruscans (the principle cultural influences on the Romans). The Romans though until 300 BC remained pretty much ungroomed.

It was only with the introduction of the fashion of shaving during the age of Alexander that the Greeks began to shave. This of course also happened in the so-called area of Magna Graecia in southern Italy which was controlled by Greek colonies. From there the fashion was introduced to the Romans.

It finally took a firm hold in Rome in about the third century BC. The great general Scipio Africanus is believed to have been the first to have begun the fashion of shaving daily. During the third century BC many barbers from the Greek parts of Sicily moved to Rome and opened shops.

Indeed a skilled tonsor (barber) could make good money in Rome. For shaving was neither a pleasant not a simple matter. The Romans lacked the high quality steel of today, so a razor (novacula) will have blunted very quickly. A visit to the tonsor may therefore have involved shaving, waxing and the use of tweezers to remove the various facial hairs.

Of course Rome was not completely immune to the whims of fashion. Especially in the late republic it was seen as very fashionable for young men to keep a small, well-groomed beard (barbula).

The late republic was indeed a time in which young rakes seemed to take to grooming in a big way. Cicero describes some of the followers of the Catalina as ‘shining with ointments’.

The general tradition of clean shaven Romans remained, however, fairly unbroken until the reign of emperor Hadrian.

There are two schools of thought regarding Hadrian. Either he was so taken by Greek culture that he adopted the Greek tradition of wearing a beard. Or his face was slightly disfigured, possibly by a scar, and he sought to hide it from view. Whatever, the reason, nothing quite set the fashion like the imperial court.

Once Hadrian introduced it, the beard was set to stay for some time, until the reign of Constantine the Great who reversed the trend. Thus the men of the empire returned to being mostly clean-shaven.

As for Roman men’s hairstyles, they tended all to keep their hair cut short. Some very vain ones might have had their hair curled with curling irons, whilst being pampered for hours at the barbers’, but they were a small minority. Romans tended to see such affectations as effeminate.

Under Marcus Aurelius the fashion for shaving one’s head clean was introduced, whilst early Christians tended to have their hair and beards cut short.

Women, in Rome, just as in any other civilization to this day, wore far more elaborate hairstyles than their men folk.

Young women simply gathered their hair into a bun at the back of the neck, or coiled it into a knot a the top of the head.

Married women’s hairstyles were more complicated. At first, the women of early Rome wore their hair in Etruscan fashion, keeping all of it tied up tightly with ribbons on the very crown of the head (tutulus). Though this strange arrangement disappeared very soon, though some priestesses still retained its use.

Already as early as the second century BC caustic soap made of tallow and ashes was imported from Gaul to dye ladies hair a reddish-yellow colour.

The age of the Flavian emperors (Vespasian, Titus and Domitian) is largely seen as the age of the most flamboyant fashion in woman’s hairstyles.

One of the styles used largely at court had the hair arranged in several layers, falling to the face in an abundance of ringlets.

Such fashion in hairstyle required the services of an expert female hairdresser who also doubled as make up artist (ornatrix), as well as additional hair pieces to be added to create such a mass of hair.

Hair pieces, wigs, hair lotions and dyes were all known to the Romans.

In fact blonde hair was a sought after commodity, traded with the Germanic tribes beyond the Rhine and Danube.

Byzantine Dress – Dress of Constantinople

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.