Last Updated on November 27, 2023 by Vladimir Vulic

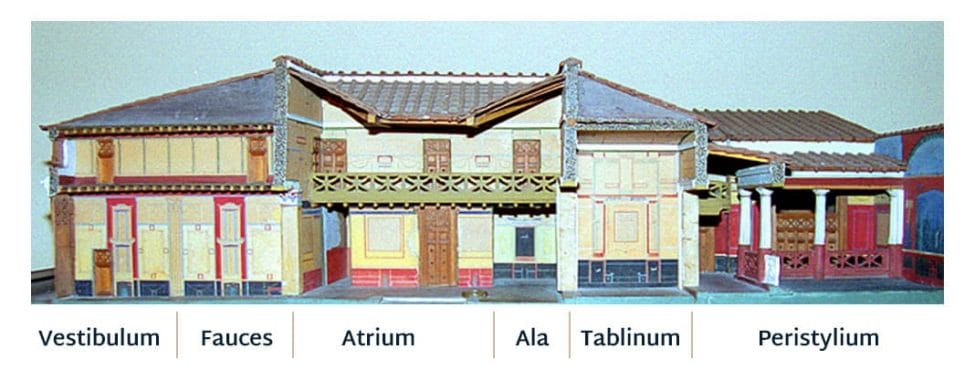

Early Italian houses grouped around the atrium, with a small garden, the so-called hortus, at the back.

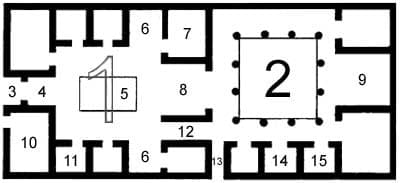

The classic Roman house, however, was divided into two parts. The first part grouped around the atrium, the second around the peristylium. The peristylium having developed out of the earlier hortus.

The atrium and the peristylium were perfect adaptions to the heat of the Mediterranean. They were open to the sky, letting fresh air in to circulate among the corridors and rooms.

In the atrium a small pool, the impluvium would catch the rainwater, whereas in the peristylium, the rain would water the plants. Further to the impluvium there was an underground tank connected to it which could catch any excess rainwater.

The Roman house is very much a house built for the people of southern Europe. So much so, that when the Romans built their houses in northern Italy or the northern European provinces, they adopted a system of heating, circulating warm air under the floors and along the walls.

It was constructed to face inward. Meaning it generally had no windows at all, but drew its air and light from the openings of the atrium and peristylium.

The house was normally only built on the ground floor, and if there was a first floor, it was small and limited to few rooms.

Rooms were designed for one specific purpose only, the triclinium being for dining, a cubiculum for sleeping, etc.

An interesting thing to note about the layout of the Roman house, is that the names given to the front part of the house around the atrium are Latin, whereas those in the back are largely Greek.

The typical Roman house was, in general, only occupied by one family. (Although one must consider that Roman families were generally enlarged families, including several generations.)

- Atrium

- Peristylium

- Vestibulum

- Fauces

- Impluvium

- Ala

- Triclinium

- Tablinum

- Exhedra/Oecus

- Taberna

- Cubiculum

- Andron

- Posticum

- Bathroom

- Cucina (kitchen)

Vestibulum and Fauces

A Roman house did not open directly onto the road, but into a small passage way, the vestibulum, the corridor which led from the main door onwards into the atrium was called the fauces.

The Posticum

Aside from the main door, there was a servants’ entrance, the posticum, usually positioned at the side of the house. It was used slaves, servants, humble visitors or sometimes even by the master of the house, who sought to leave the house unnoticed by the prying eyes of onlookers in the main street.

The Atrium

The atrium originally was the bedroom of the mother of the family in an old Latin household. Hence a bed lectus genialis stood opposite the main entrance. The Romans kept the bed standing, as a symbol of the sanctity of marriage (the bride was still placed upon it by the groom as part of the marriage ceremony). But to them it served only symbolic use.

A further symbol connected with the atrium was the hearth. In early houses the hearth, which all its symbolisms of homeliness, was situated in the atrium the centre of the house and domestic life.

But the more classic Roman houses don’t have a hearth in the atrium. In fact it remains unclear where the highly symbolic hearth was thereafter moved to.

- The impluvium was the shallow pool sunk into the floor to catch the rainwater. Some surviving examples are beautifully decorated. The opening in the ceiling above the pool called for some means of support for the roof. And it is here where one differentiates between five different styles of atrium.

- atrium tuscanium: this type had no columns. The weight of the ceiling was carried by the rafters. though expensive to build, this seems to have been the most widespread type of atrium in the Roman house.

- atrium tetrastylum: this type had one column at each corner of the impluvium.

- atrium corinthium: this type was similar to the atrium tetrastylum but had a greater opening in the roof and a greater number of columns.

- atrium displuviatum: the roof actually sloped towards the side walls, a large rainwater therefore ran off into other outlets than the impluvium.

- atrium testudinatum: this atrium had no opening in the roof at all and was only seen in small, unimportant houses.

As the centrepiece of the house The atrium was the most lavishly furnished room. Also it contained the little chapel to the ancestral spirits (lararium), the household safe (arca) and sometimes a bust of the master of the house.

The Tablinum

The tablinum was the large reception room of the house. It was situated between the atrium and the peristylium. The tablinum generally had no wall separating it from the atrium at all and little if any walls dividing it from the peristylium. It was only separated from the atrium by a curtain which could easily be drawn back and toward the peristylium it was separated by a wooden screen or wide doors. Hence if the doors/screens and curtains of the tablinum were all opened to increase ventilation during a hot day, one could see from the atrium through the tablinum into the peristylium. In the early days, the tablinum would have acted as the study of the head of the family, the paterfamilias.

The Alae

The alae (alae is the plural of ala, the word ala means ‘wing’) were the open rooms on each side of the atrium. Their use is largely unknown today. One knows that in the early Italian houses, which had a covered atrium, the alae had windows to allow light to enter the house. However, with the introduction of the opening in the roof above the atrium and the general abandoning of windows in the Roman house, the alae became largely obsolete. It appears more that they were incorporated into the house in accordance to tradition, rather than for any specific use.

The Triclinium

The triclinium was the Roman dining room. In earlier days the meals were eaten in the atrium, the tablinum, or a dining room above the tablinum, known as the cenaculum.

But with the introduction of the Greek practice of reclining when eating, the triclinium was set aside as a room especially for dining in.

In fact, in many houses once would find several triclinia, rooms designated as dining areas, allowing the family a choice of which room to eat in on any particular day.

The Andron

The andron was the name given to a passageway from the atrium to the peristylium.

The Peristylium

The peristylium (sometimes called the peristyle in English) was in effect the garden of the house. Though in the case of the Roman house, it was incorporated into the house itself and was usually surrounded by columns supporting the roof.

In it were grown herbs and flowers, particularly roses, violets and lilies it appears.

Small statues and statuettes and other ornamental artwork or outdoor furniture would adorn the space which, on sunny days, would be used as an outside dining area.

The Exhedra and the Oecus

Just as the tablinum lay behind the atrium, continuing the space down the center line of the house, so did the exhedra extend behind the peristylium. It was a spacious room, of similar proportions to the tablinum and acted as a large communal dining room or a lounge. The oecus (from the Greek oikos for ‘house’ or ‘room’) appears to have been the same thing as the exhedra, but by a different name. If the inside of this room was decorated by columns lining the walls, it was known as a oecus corinthium.

The Cubiculum

The cubiculum was the bedroom of the Roman house.

Those bedrooms situated around the atrium tended to be smaller than those round the peristylium. To the Romans these rooms were apparently of less importance than the other rooms of the house. The ceilings were vaulted and lower above the bed, often making the room appear a cramped and stuffy place.

According to the apparent tradition of the Roman house of giving each room a very specific use, the floor mosaics of the cubiculum often clearly marked out the rectangle where the bed was to be placed.

Sometimes in front of the bedroom there was a small antechamber, the procoeton, where a personal servant would sleep.

The Taberna

The taberna could be a room in the Roman house which surrounded the atrium, but which had its own entrance from the outside and didn’t lead into the interior of the house. These little rooms hence could be used as shops. Usually there was a brick counter to display goods by the entrance. Inside there usually one or more back rooms. There normally was a floor added, cutting the tall room in half to create two low floors, the upper floor being called the pergula. These cramped flats housed the very poor, perhaps a poor client family loyal to the family who inhabited the house.

A taberna though was not necessarily meant as housing for tenants, but could also be a simple shed in which to keep various things not suitable for storage indoors.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.