Last Updated on December 18, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Roman society was governed by class and so in effect there was three separate army careers possible, that of the common soldier in the ranks, that of the equestrians and that for those destined for command, the senatorial class.

Infantry Positions

| Miles, also Miles Gregarius, Gregalis | Ordinary soldier |

| Strator | Groom or equerry (horse groom) to an officer |

| Decanus | leader of an eight man tent or barracks party |

| Vexillarius | bearer of the vexillum standard signifying a small unit detached from the legion. |

| Immunis | longer serving soldier or army member holding special skills, who are excused from chores such as latrine duties, etc.. |

| Sesquipilarius | Pay grade in the army. Receives one and a half times regular pay. |

| Duplicarius | Pay grade in the army. Receives double pay. |

| Principalis | over arching term for any low ranking officer (for example optio) receiving either one and a half times or double pay. |

| Tesserarius | Keeper of the watchword, administrative assistant to HQ Staff, third in command to a centuria |

| Optio | Second in command to Centurio, Receives Double Pay (Duplicarius). |

| Magister Ballistariorum | low ranking officer, equivalent to optio, in command of artillery |

| Optio Valetudinarii | low ranking officer in charge of hospital |

| Optio ad Spem Ordines | an optio who has been marked out for promotion to Centurion once a vacancy becomes available |

| Signifer | standard bearer of the maniple (two centuries), who kept the pay and savings accounts of the soldiers |

| Cornicen | hornblower, assistant to Centurions |

| Imaginifer | bearer of the standard depicting the emperor |

| Campidoctor (also doctor) | drill instructor |

| Custos Armorum | Keeper of the armoury/arsenal |

| Medicus | Medical Orderly or Army doctor, the latter could also be called medicus ordinarius and would be deemed an officer |

| Aquilifer | standard bearer of the legion’s eagle standard (aquila) |

| Centurio | commander of a centuria |

| Centurio Hastatus Posterior | sixth in command of a cohort |

| Centurio Princeps Posterior | fourth in command of a cohort |

| Centurio Pilus Posterior | second in command of a cohort |

| Centurio Hastatus Prior | fifth in command of a cohort |

| Centurio Princeps Prior | third in command of a cohort |

| Centurio Pilus Prior | first in command of a cohort |

| Ordinatus | term increasingly used for centurion from second century onwards. |

| Primi Ordines | Centurions of the First Cohort |

| Primus Pilus (also Primipilus) | first centurion of the legion |

| Tribunus Legionis | high ranking staff officer of a legion, usually of equestrian rank |

| Praefectus Castrorum | camp commander, usually ex primus pilus (called a primipilaris), third in the hierarchy of legion |

| Tribunus Laticlavius | senatorial tribune, second in command of a legion |

| Praepositus | temporary legion commander, or commander of a force (vexillatio) of the numeri |

| Praefectus Cohortis | commander of an auxiliary cohort |

| Legatus Legionis | legion commander |

Note: a centurio princeps could also be the senior centurion of an auxiliary infantry force.

Centurio trecenarius is another name for a centurio hastatus of the first cohort.

Officium – Governor’s Staff – in army provinces governors would be legates, so at times the officium could easily have been connected with a legion’s HQ, the principia.

Cavalry Positions

| Eques, also Equitis | cavalryman |

| Curator | accountant of a turma |

| Decurio | commander of a turma |

| Decurio Princeps | senior decurion |

| Praefectus Alae | commander of an auxiliary cavalry unit |

4th Century Army Positions

| Limitaneus | frontier soldier (permanently stationed) |

| Ripariensis | frontier soldier (mobile) |

| Comitantensis | soldier of the mobile field army |

| Magister | low ranking officer equivalent to earlier Optio |

| Draconarius | dragon standard bearer |

| Protector | officer cadet (protectores – officer cadet corps) |

| Biarchus | fifth in command |

| Centenarius | fourth in command |

| Ducenarius | second in command |

| Dux | army commander |

| Magister equitum | commander of the imperial cavalry forces |

| Magister peditum | commander of the imperial infantry forces |

The Men from the Ranks

The most significant step in any successful army career of a Roman plebeian was the promotion to the centurionate. To become a centurion meant having become an officer.

The main supply for the centurionate of the legions did indeed come from the ordinary men from the ranks of the legion. Though there was a significant number of centurions from the equestrian rank.

Some of the late emperors of the empire prove very rare examples of ordinary soldiers who rose all the way through the ranks to become high-ranking commanders. But in general the rank of primus pilus, the most senior centurion in a legion, was as high as a ordinary man could reach.

Though this post brought with it, at the end of service, the rank of equestrian, including the status – and wealth ! – that this elevated position in Roman society brought with it.

The ordinary soldier’s promotion would most likely start with the rank of optio. This was the assistant to the centurion who acted as a kind of corporal. Having proven himself worthy and earned promotion an optio would then be promoted to being a centurio, an officer in command of eighty legionaries.

However for this to happen, there would have to be a vacancy. If this was not the case he might be made optio ad spem ordinis. This marked him out by rank as ready for the centurionate, merely waiting for a position to become free. Once this happened he would be awarded the centurionate.

However, if the step from legionary to optio to centurio provides the ideal, simple example, we must accept that the reality was not necessarily always quite as straightforward.

Centurion

The centurion’s armour varied widely, perhaps it was even a matter of individual choice. The centurion depicted wears leather. The rings (torques) and circular plaques (phalerae) on his torso are awards he has won in battle, comparable to medals in modern day armies.

The horsehair crest across his helmet made him easily recognizable by everyone, even in the chaos of batte, as a officer of considerable rank.

The greaves he wears to protect his shins are also a sign of his being a centurion. A cape was usually also seen as a mark of a centurion. Although, given that their style of dress may well have been down to their own choice, this centurion may not be at all out of place without such a cape.

Note also the vine rod he holds in his hand. A further insignia of his rank and one he would happily use to beat unruly soldiers with to enforce discipline.

The army provided several stepping stones up the ladder of promotion. The very first step might be considered the position of decanus, granting the soldier seniority over his tent party. Given that a tent held eight men, this was a very minor position.

Further steps allowed the promotion to tesserarius, signifer, or perhaps even cornicen. It isn’t known if, when a temporary vexillarius was needed to carry the vexillum standard for an irregular detachment from the legion, this represented a promotion of sorts for an ordinary soldier.

Once the position of optio was achieved, an alternative promotion might be that of decurion in the cavalry attached to the legion.

So the successful army career of a soldier from the ranks was not necessarily clear-cut, but depended on what opportunities arose at the time.

However once the status of officer had been achieved, there was further division between the seniority of centurions. (It is fair to assume that a similar ranking of seniority existed among the decurions of the cavalry.) And as a newcomer, our former optio would start on the lowest rung of this ladder.

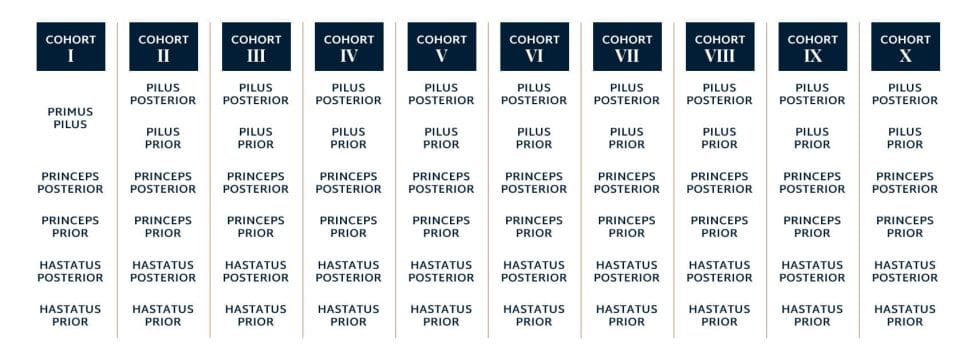

With their being six centuries to each cohort, each regular cohort had 6 centurions.

The centurion commanding the century most forward was the hastatus prior, the one commanding the century immediately behind his, was the hastatus posterior.

The next two centuries behind them were commanded respectively by the princeps prior and the princeps posterior. Finally the centuries behind these were commanded by the pilus prior and the pilus posterior.

Seniority between the centurions was most likely such that the pilus prior commanded the cohort, followed by the princeps prior and then the hastatus prior. Next in line would be the pilus posterior, followed by the princeps posterior and finally the hastatus posterior.

The number of his cohort was also part of a centurion’s rank, so the full title of the centurion commanding the third century of the second cohort would be centurio secundus hastatus prior.

The first cohort was the most senior in rank. All its centurions outranked the centurions of the other cohorts. Though according to its special status, it had only five centurions, their being no division between pilus prior and posterior, but their role being filled by the primus pilus, the highest ranking centurion of the legion.

The Equestrians

Under the republic the equestrian class supplied the camp prefect and the tribunes. But generally there was not a strict hierarchy of different posts during this era.

With the increased numbers of the auxiliary commands becoming available under Augustus, a career ladder emerged with various posts available to those of equestrian rank.

The three main military commands (called the tres militiae) in this career were:

- Praefectus cohortis = commander of an auxiliary infantry

- Tribunus legionis = military tribune in a legion

- Praefectus alae = commander of an auxiliary cavalry unit

With both the prefect of an auxiliary cohort and the prefect of the cavalry, those commanding a millaria unit (roughly a thousand men) were naturally deemed senior to those commanding a quingenaria unit (roughly five hundred men). So for a praefectus cohortis to move from command of a quingenaria to a millaria was a promotion, even if his title would not actually change.

The various commands were held one after another, each one lasting three or four years. They were generally given to men who had already gained experience in civilian positions of senior magistrates in their home towns and who were perhaps in their early thirties.

Commands of a cohort of auxiliary infantry or a tribunate in a legion were usually granted by the provincial governors and hence were largely political favours.

Though with the award of cavalry commands it is likely that the emperor himself was involved. Even with some of the commands of millaria auxiliary infantry cohorts it appears that the emperor made appointments.

Some equestrians went on from these commands to become legionary centurions. Others would retire to administrative posts.

There was however a very few enormously prestigious posts open to experienced equestrians. The special status of the province of Egypt meant that the governor and legionary commander there could not be a senatorial legate. It hence fell to an equestrian prefect to hold command of Egypt for the emperor.

Also the command of the praetorian guard was created as a post for equestrians by emperor Augustus.

Though in later days of the empire naturally the increasing military pressures began to blur the lines between what was reserved strictly for the senatorial class or for equestrians. Marcus Aurelius appointed some equestrians to legionary commands simply by making them senators first.

The Senatorial Class

In the changing Roman empire under many reforms introduced by Augustus the provinces continued to be governed by senators. This left open to the senatorial class the promise of high office and military command.

Young men of the senatorial class would be posted as tribunes to earn their military experience. In every legion of the six tribunes one position, the tribunus laticlavius was reserved for such a senatorial appointee.

Appointments were made by the governor/legatus himself and hence were among the personal favours he make to the young man’s father.

The young patrician would serve in this position for two to three years, beginning in his late teens or early twenties.

Thereafter the army would be left behind for a political career, gradually climbing the steps of the minor magistracies which could last for about ten years, until finally the rank of legionary commander could be reached.

Before this however, usually would come another term of office, most likely in a province without legions, before reaching the consulate.

The province of Egypt, so important for its grain supply, remained under the emperor’s personal command. But all the provinces with legions within them were commanded by personally appointed legates, who acted both as army commanders as well as civil governors.

After having been consul an able and reliable senator might be appointed to a province containing as many as four legions. The length of service in such an office would generally be for three years, but it could vary considerably.

Legatus (1st Century AD)

The legatus was the commander of a legion. He would be of senatorial rank.

Here he wears a bronze chest plate. The purple on his tunic points to his being of the senatorial order.

Almost half of the Roman senate was required to at some time serve as legionary commanders, indicating just how competent this political body must have been in military matters.

The length of office for able commanders however increased with time. By the time of Marcus Aurelius it was well possible for a senator of great military talent to hold three or even more successive major commands after he had held the consulate, after which he might progress onto the emperor’s personal staff.

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.