Last Updated on December 25, 2021 by Vladimir Vulic

Life: AD c. 279 – 312

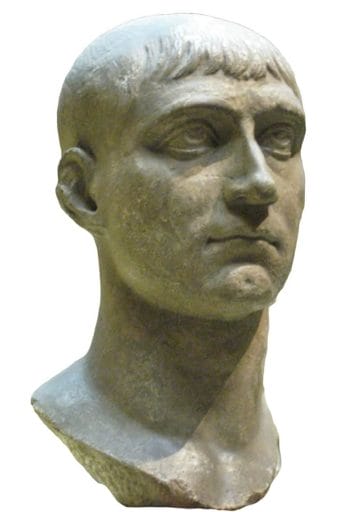

- Name: Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius

- Born in AD ca. 279 possibly in Syria.

- Became emperor in 28 October AD 306.

- Wife: Valeria Maximilla (two sons; Valerius Romulus; unknown).

- Died at Milvian Bridge at Rome, 28 October AD 312.

Marcus Aurelius Valerius Maxentius was born around AD 279 as the son of Maximian and his Syrian wife Eutropia.

He was made a senator and even was given Galerius’ daughter Valeria Maximilla in marriage in an attempt to confirm his status of the son of an emperor.

But other than these honours he received nothing. No consulship to groom him for power, no military command.

First he suffered the indignity together with Constantine of being passed over as Maximian and Diocletian both resigned in AD 305, when they both had to watch the relative unknowns of Severus II and Maximinus II Daia accede to what they saw as their rightful places.

Then at the death of Constantius Chlorus in AD 306 Constantine was granted the rank of Caesar, leaving Maxentius out in the cold.

But Maxentius was not as helpless as the emperors of the tetrarchy might have believed. The population of Italy was greatly dissatisfied. Had they enjoyed tax-free status, then under the reign of Diocletian northern Italy had been denied this status, and under Galerius the same happened to the rest of Italy, including the city of Rome. Severus II’s announcement that he wished to abolish the praetorian guard altogether also created hostility among Italy’s main military garrison against the current rulers.

It was with this background that Maxentius, backed by the Roman senate, the praetorian guard and the people of Rome, rebelled and was hailed emperor.

If northern Italy did not rebel, it was more than likely only due to the fact that Severus II had his capital at Mediolanum (Milan). The rest of the Italian peninsula and Africa though declared in favour of Maxentius.

At first Maxentius sought to tread carefully, seeking acceptance with the other emperors. It was in that spirit that he only assumed the title of Caesar (junior emperor) at first, hoping to make it clear that he did not seek to challenge the rule of the Augusti, particularly not that of the powerful Galerius.

Trying to win greater credibility for his regime – and perhaps also seeing the necessity for someone with more experience, Maxentius then called his father Maximian out of retirement. And Maximian, who had been very reluctant to relinquish power in the first place, was very eager to return.

But still no recognition by other emperors was forthcoming. On Galerius behest, Severus II now led his troops on Rome to overthrow the usurper and to reestablish the authority of the tetrarchy.

But at that point the authority of Maxentius’ father proved decisive. The soldier’s refused to fight the old emperor and mutinied. Severus II fled but was caught and, after being paraded through the streets of Rome, was held as a hostage in Rome to deter Galerius from any attacks.

It was now that Maxentius declared himself Augustus, no longer seeking to win favour with the other emperors. It was only Constantine who recognized him as Augustus. Galerius and the other emperors remained hostile. so much so, that Galerius now marched into Italy himself. But he too was now to realize just how dangerous it was to advance his troops against Maximian, a man whose authority many of the soldiers respected more than his own. With many of his forces deserting, Galerius had to simply withdraw.

After this victory against the most senior of the emperors, all seemed well for the co-Augusti in Rome.

But their success brought about the defection of Spain to their camp. Had this territory been under the control of Constantine, then its change of allegiance now made them a new, very dangerous enemy.

Then Maximian, in a surprising twist of fate in April AD 308, turned against his own son. But on his arrival in Rome in AD 308, his revolt was successfully stifled and he had to flee to Constantine’s court in Gaul.

The Conference of Carnuntum where all the Caesars and Augusti met later in AD 308 then saw the forced resignation of Maximian and the condemnation of Maxentius as a public enemy.

Maxentius did not fall at that point. But the praetorian prefect in Africa, Lucius Domitius Alexander, broke away from him, declaring himself emperor instead.

The loss of Africa was a terrible blow to Maxentius as it meant the loss of the all-important grain supply to Rome. In consequence capital was struck by famine. Fighting broke out between the praetorians who enjoyed a privileged food supply and the starving population.

Late in AD 309 Maxentius’ other praetorian prefect, Gaius Rufius Volusianus, was sent across the Mediterranean to deal with the African crisis. The expedition was successful and the rebel Alexander was killed.

The food crisis was now averted, but another far greater threat now was to arise. Constantine was, later history proved that all too well, a force to be reckoned with. If he was hostile toward Maxentius ever since the break away of Spain, then he now (following the death of Severus and Maximian) styled himself as western Augustus and hence laid claim to complete rule of the west. Maximian was hence in his way.

In AD 312 he marched into Italy with army of forty thousand elite troops.

Maxentius had command of at least four times as great an army, but his troops did not possess the same discipline, nor was Maxentius’ an equal general to Constantine. Constantine moved into Italy without letting his army sack any cities, thereby winning the support of the local population, which by now was thoroughly sick of Maxentius.

The first army sent against Constantine was defeated at Augusta Taurinorum.

Maxentius numerically still held the upper hand, but at first decided to rely on the further advantage the city walls of Rome would grant his army of Constantine.

But being unpopular with the people (particularly after the food riots and starvation) he feared treachery on their part might sabotage any defence he might stage. And so his force suddenly left, heading north to meet Constantine’s army in battle.

The two sides, after a first brief engagement along the Via Flaminia, finally clashed close to the Milvian Bridge. Had the actual bridge over the Tiber initially been made unpassable in order to hamper Constantine’s advance towards Rome, then now a pontoon bridge was thrown over the river in order to carry Maximian’s troops across. It was this bridge of boats which Maximian’s soldiers were driven back onto as Constantine’s forces charged them.

The weight of so many men and horses caused the bridge to collapse. Thousands of Maxentius army drowned, the emperor himself being among the victims (28 October AD 312).

Historian Franco Cavazzi dedicated hundreds of hours of his life to creating this website, roman-empire.net as a trove of educational material on this fascinating period of history. His work has been cited in a number of textbooks on the Roman Empire and mentioned on numerous publications such as the New York Times, PBS, The Guardian, and many more.